Episode Transcript

Transcripts are displayed as originally observed. Some content, including advertisements may have changed.

Use Ctrl + F to search

0:00

Researchers are gaining new insights into the science

0:02

of well-being all the time, but modern happiness

0:04

scientists are still standing on the shoulders

0:06

of some pretty old school giants. I'm Dr.

0:08

Laurie Santos. And in the new season of the Happiness

0:10

Lab, I'll be introducing you to many of these

0:12

ancient thinkers, philosophers, and spiritual

0:15

leaders. People from Mac in the day who figured

0:17

out important well-being tips that are still totally

0:19

relevant right now. We'll learn about all their great

0:21

ideas and how we can put their classic tips

0:24

into practice today. Listen to the Happiness

0:26

Lab on the iHeartRadio app Apple Podcasts

0:28

or wherever you get your podcasts.

0:34

Acast powers the world's best

0:36

podcast. Here's a show

0:38

that we recommend. I'm

0:41

Jesse Crooked Shank, and I've always been told

0:43

have a face for podcasting. So I

0:45

launched a podcast. It's called phone

0:47

a friend because each week I'll break down the biggest

0:49

stories in pop culture. When I have questions,

0:52

I get to phone a friend. I'll phone the

0:54

royal watcher to find out why Prince Harry

0:56

is acting like a real housewife. I'll

0:59

phone a tweet to please explain euphoria,

1:01

and maybe I'll even phone a back stream boy to find

1:03

out if I still have a chance. I don't.

1:06

Okay. New episodes drop every Thursday

1:08

wherever you get your podcast.

1:13

Acast helps creators launch,

1:15

grow and monetize their podcast

1:17

everywhere. Acast dot com.

1:32

It's the ancients on History Hit.

1:35

I'm Tristan Hughes, your host. And

1:37

in today's episode, we'll get this. We're

1:39

talking about the worst single

1:41

day in the history of life

1:44

on earth. The extinction of

1:46

the dinosaurs that occurred some

1:48

sixty six million years ago

1:51

when an asteroid, some seven

1:54

miles across slams into

1:56

the earth causing the extinction

1:59

of more than half of the known

2:01

species in the world,

2:04

including, of course, most famously,

2:07

the dinosaurs. So

2:09

what do we know about

2:11

this paleons homological armageddon.

2:15

What do we know about this day? The

2:17

days that followed the months, the years

2:19

that followed how the earth began

2:21

to recover from this absolute

2:25

catastrophe. What to explain

2:27

all about these last days

2:29

of the dinosaurs and the creation

2:32

of the world we know today, I

2:34

was delighted to interview the

2:36

highly renowned science writer

2:39

Riley Black. Riley has written

2:41

a number of books all about dinosaurs

2:44

about paleontology in one of our most

2:46

recent books is all about this

2:48

topic, about the mass extinction,

2:50

about the asteroid, and what

2:53

followed, what happens next. There's

2:55

a great pleasure to interview Riley all about this.

2:57

No doubt, it's gonna be a very

3:00

very popular topic, and I really

3:02

do hope you enjoy. So that

3:04

further ado, to talk all about this

3:06

mass extinction event, the fall of the

3:08

dinosaurs, this great asteroid, the

3:11

worst day In the

3:13

history of life on earth,

3:16

here's Riley. Riley,

3:19

it is wonderful to have you on the podcast today.

3:21

I was so lovely to be Anne. Thank you.

3:24

You're more than welcome. And we've done a

3:26

few dinosaur episodes in the past with the

3:28

likes of Steve Prasati and Henry Jesus. Wonderful

3:30

now to have you all as well. To talk about

3:32

this through a final days of the dinosaurs

3:34

and what happened next? Because Friday, I

3:36

mean, correct me if I'm wrong, but is it fair to say

3:39

that the meteorites, it takes all

3:41

the headlines, but what happens

3:43

after the impact itself in those

3:45

days weeks, months,

3:47

years, thousands of years following that and

3:49

the recovery of earth. Is this fair to say that

3:51

that part of the story is sometimes a little

3:53

overlooked? Oh, I'd say it's a lot overlooked.

3:56

Really, I haven't been so concerned with

3:58

where our favorite dinosaurs went for

4:00

so long. I feel like sometimes we

4:03

even forget that this was a mass extinction. This

4:05

was the world's fifth mass extinction

4:07

of seventy five percent, even just the animals

4:09

we know about. Disappeared literally

4:11

overnight. And, yes, the

4:14

asteroid, it's a huge thing. It inspired

4:16

two blockbuster movies, like, in the nineteen nineties,

4:18

Deep Impact and Armageddon came out same summer

4:20

because people were so fascinated by this idea

4:23

that how life recovered, how it came back, how

4:25

we got into the age of mammals,

4:27

as we call it now, often gets overlooked.

4:30

And I think it's a historical thing. You can go

4:32

back a hundred years ago before we knew

4:34

anything about the asteroid impact and

4:36

read paleontology textbooks. And

4:38

paleontologists were going, like, we don't know

4:40

why dinosaurs are around for so long.

4:42

They're big and they're ugly and they're

4:44

weird. Ma'am will sort of take and over a long time

4:46

ago. We don't understand any of this. Maybe

4:48

they just, like, got too big. I don't know. So

4:50

this is a mystery for so long, and then we have

4:52

this, like, fantastic. Kind of solution

4:55

to it. But you're entirely right that

4:57

the recovery from that. What happened

4:59

in the next, you know, hours, days, weeks, months,

5:02

million years after? We usually

5:04

take that as a given. Like, of course, life would come

5:06

back, and that's not really the case. mean,

5:08

absolutely not. And one thing I'd love to focus

5:10

on first because we were just chatty about it before

5:12

we started recording is in

5:14

this field of paleontology, which you

5:17

focus on, Riley. It sounds as if

5:19

more and more evidence, more and more research

5:21

is coming to the fore almost every

5:24

week. Oh, entirely. So

5:26

on average, even just like new dinosaur

5:29

species, like the rate at which for finding them. And

5:31

this is just dinosaurs. This thing, nothing of

5:33

fossil plants or insects or things that lived in

5:35

the oceans or any of that. Just our favorite

5:37

dinosaurs. There's a new species named about

5:39

every two weeks. And then on top of

5:41

that, there's all the environmental reconstructions

5:44

and what were they eating and what did they look like and

5:46

all this information. This field seems

5:48

to be incredibly busy. I did not intend

5:50

to be a full time paleontology writer.

5:52

It just kind of became that way because there is

5:54

so much to talk about, I feel

5:57

inundated sometimes by the amount of new

5:59

research coming in. Because

6:01

it really is it's not just a lost world.

6:03

It's one place in time. We're talking about hundreds of millions

6:05

of years of evolution all around the planet.

6:08

And anytime you find any one particular thing,

6:10

It connects to something else. And

6:12

it's a group of hundreds of experts

6:15

around the world, basically arguing over the same

6:17

puzzle and what goes where and sometimes we very much

6:19

agree and sometimes we very much don't agree. But

6:22

you can see why, like, both through just rate of discovery

6:24

in the way that science works. Yes.

6:26

This is an incredibly vibrant

6:28

field. I mean, Riley, okay.

6:30

You have written this lovely narrative

6:33

book about the end of the dinosaurs and

6:35

what happened next. And so

6:37

as background set the scene sixty

6:39

six million years ago before the

6:42

meteorite, crashes into earth,

6:44

what does the world look like?

6:46

So the world, at the time, if we were to have, like,

6:48

the big picture view, it's little

6:50

bit warmer that it is now, there's not as

6:52

much global ice set, the poles. You

6:54

have the remnants of this ancient seaway that

6:56

used to split North America in half most

6:58

of our famous dentures, most of what we know about

7:01

from this time period comes from

7:03

areas in Montana and Western South

7:05

Dakota, Globe and Wyoming and Utah,

7:08

all these basically pockets for the seaway

7:10

was receding. So we're talking about a global event,

7:12

but most of what we know comes from

7:14

Western North America so far. And

7:17

at the time you have your community of, like,

7:19

some of our most favorite dinosaurs. There's

7:21

dinosaurs. Right? There's triceratops at Montesaurus.

7:24

You know, from things that are about the size

7:26

of a sparrow all the way up to, like, these

7:28

nine ton monsters basically, you

7:31

know, they're filling the environment. There's

7:33

been a lot of discussion debate over the years

7:35

of, you know, where dinosaurs fading away.

7:37

Was their diversity going down? There's not really

7:39

a sign of, like, anything going wrong. Is

7:41

this a perfectly average day

7:44

at the end of the Cretaceous, going on

7:46

much the same way as it had for millions

7:48

of years prior. To give you an

7:50

idea, T Rex was around for about two million

7:52

years, from about sixty eight to sixty six

7:54

million years ago. So if not

7:57

for that asteroid, if that

7:59

asteroid had missed, everything would have continued

8:01

going on as it had. This was a

8:03

world that was full of dinosaurs,

8:06

a diversity of little mammals skirring around. There

8:08

were birds, not just birds with beaks, but

8:10

birds with teeth, you know, terasores were in the

8:12

air, out in the seas. You had things like pieziasores

8:14

and mosesores. Swimming around

8:16

those cold chilled ammonites. They're so fun

8:19

to collect. We're out in the seas.

8:21

So it was like what we think of sometimes

8:23

in ecology is like a climax. Community. And

8:25

that there are multiple interconnected tiers.

8:28

So you have Apex predators, competitors

8:30

in the middle, and herbivores of all shapes and sizes.

8:32

So this is really well formed in, like,

8:34

established community of organisms.

8:37

And then basically, snap your fingers,

8:39

that all changed.

8:41

It's all changed indeed. I mean, one

8:43

more quick question before we delve into that. I

8:45

noticed in your book the name of one particular

8:47

place, Hell Creek I mean,

8:49

what is this? There seems to be an important

8:52

location for this time in pre

8:54

pre pre history.

8:55

Right. So if you travel through Montana,

8:58

especially the eastern part of the state. You know, these

9:00

little roadside sounds like Iqalaka that you'll

9:02

pass through. And you look around you and you

9:04

see this rolling landscape, and

9:06

that is what we call the Hell Creek

9:08

formation. So is this unit of

9:10

rock that spans about two million

9:13

years. And if you want to find

9:15

some of these dinosaurs, if you're gonna go looking,

9:17

for a tyrannosaurus or triceratops. This is

9:19

where you go for it. And it's incredibly

9:22

fossil rich. People have sometimes done fossil surveys

9:24

just like picking up every single thing they could find, like,

9:26

in a mile radius. And saying,

9:28

okay, what does like the population of the animals look

9:30

like? So it's incredibly phospholiferous. It's

9:32

told us an incredible amount I've been lucky

9:34

enough to go out and do some field work out there, and I

9:36

love these particular places called microsites, because

9:39

microsites get like a census of

9:41

who is around. So you don't get big bones

9:43

but you have a lot of teeth. You got scales from

9:45

fish. You have bits of mammal jaw. Things

9:47

like that kinda helps paint this picture. So,

9:49

yeah, so much of what

9:52

we know about what happened before

9:54

the impact and after comes from this area

9:56

because we have the before and after snapshots.

9:58

It's not just about the whole creek formation

10:00

where our favorite dinosaurs are. There's an overlying

10:03

geological formation that basically

10:05

you can track, okay, you've got dinosaurs here.

10:07

We can find the boundary layer where the impact

10:10

occurred, and then we can see life

10:12

for the million years or so after that.

10:14

And that is incredibly useful in figuring

10:16

out who survived, who and extent,

10:18

what has shifted

10:19

around. But we really start in the book.

10:22

The story starts in what we now know

10:24

of as the Hell Creek formation. Rice.

10:26

Well, to get that therefore narrative,

10:29

let's go into the story proper writing. You're gonna

10:31

tell us the story now. We've gotta start

10:33

with the armageddon, the catastrophe

10:35

itself, what do we know therefore about

10:38

the asteroid? Right? So this is the neat

10:40

thing about the

10:41

asteroid. We have the crater. It's

10:43

in Yucatan Peninsula. It's called the Chuxu

10:45

Loop crater. It was found in the mid

10:47

twentieth century, I think, in the nineteen sixties by an oil

10:49

geologist. And they didn't quite know what they had found.

10:51

Just yet, it took quite a while to

10:53

start putting all these pieces together. But

10:56

this was made by a chunk of rock

10:58

that snacked the planet. It was about seven

11:00

miles across. It's more less it's been like into

11:03

Mount Everest. So if you can imagine Mount Everest

11:05

slamming into the planet at tens

11:07

of thousands of kilometers per hour

11:10

as the earth is turning, as the earth is spinning,

11:12

the amount of kinetic energy that was released for this.

11:14

And there's a whole backstory to that too, which I love

11:16

we often forget, like, in this fast drink, it wasn't

11:18

just, like, hanging out in our solar system

11:20

and decided to pay us a visit. This is

11:23

something that it seems to be, what

11:25

we call, a carbonaceous chondrate. So it's a kind

11:27

of asteroid that's kind of like debris.

11:29

It's leftovers from the formation of

11:31

our solar system that might have been hanging

11:33

out in this kind of Debris cloud, called

11:35

the or cloud that's around our solar

11:38

system and gradually kinda

11:40

got pulled in by the gravitational pull

11:42

of the sun and Jupiter, And this has happened

11:44

to other sort of comments and

11:46

meters and astroids before where,

11:48

like, that poll will bring something in almost kinda,

11:50

like, tractor beam. And then, like, put it under such

11:52

tension that kinda snaps and gets sent

11:55

further into our solar system. And

11:57

this was happening during

11:59

the time that dinosaurs are first evolving and

12:01

diversifying. So in a sense,

12:03

like, their conclusion was already sealed,

12:07

when they originate it. And this is

12:09

basically happening. It's just physics playing

12:11

this out and it's coming towards them until one

12:13

day. Sixty six million years ago from our present

12:15

time. This chunk of rock hits

12:17

the planet in basically modern day Central

12:20

America. And the effects

12:22

were just immediately devastating. You know, in

12:24

in the area there I

12:26

mean, whatever was living, they would pretty much be vaporized

12:28

by the amount of energy and heat. Created

12:31

by this impact. You had tsunamis

12:33

that went out from the impact

12:35

site that were as tall skyscrapers. They

12:37

had so much energy to them. That they hit

12:40

the coastline and then rebounded back. So

12:42

when we look at the crater today, it looks like a mess

12:44

because it's actually been covered over. By

12:47

the settlement moved by all the

12:49

tsunamis. And one of

12:51

the worst parts about all of this. You

12:53

have all these small effects you have. Tsunamis, you

12:55

have seismic activity that reaches

12:57

the whole peak ecosystem within about fifteen

12:59

minutes to an hour or so after impact.

13:02

But the worst part of all this, you have so much debris

13:05

that's basically pulverized by

13:07

this impact. All these little bits of rock

13:10

and glass and quartz and other things like that

13:12

get thrown up into our atmosphere. And

13:14

it starts to spread around the planet. And as these

13:16

things come down, if you've ever seen a science fiction film

13:19

with like a space shuttle, you know, reentering or

13:21

satin veerance starts to heat up from all the friction

13:23

from from hitting the air, that's what's

13:25

happening on a small scale to all these little things.

13:27

So any one particular thing, it doesn't really matter. It's

13:29

almost microscopic, how small things are.

13:32

But there's so much mass, there's

13:34

so much material that they're

13:36

all doing this, that the

13:38

friction creates what we call infrared

13:40

pulse. So basically, it heats

13:43

the air to about

13:45

what you would use to broil a chicken

13:47

in your home oven. Like, basically, the max

13:49

setting for your home oven is

13:51

what the air was like. And this is within

13:54

the first day. This is within the first twenty

13:56

four hours. So unless you

13:58

are adapted to unless

14:00

you live in water, unless you can burrow

14:02

underground, unless you have some kind of shelter

14:05

from this heat. There's no way to get away

14:07

from and it's so hot that, like, dry,

14:09

tree material, plant material out in the forest at

14:11

the time would have spontaneously caught fire.

14:13

So you're not just you don't just have the heat

14:16

You have the forest fires or things sitting here.

14:18

It's really apocalyptic, it truly is.

14:21

And that's even before we get into

14:23

all the after effects in the following years. Of

14:25

the impact went through all these. So you have

14:27

this incredible heat pulse. It's like

14:29

nothing in the world has ever been through before.

14:32

That dies down life has already taken a major

14:34

hit. Where the asteroid struck

14:37

used to be an ancient reef made of

14:39

limestone basically. So these are compressed

14:41

fossils that were made millions

14:43

of years before the impact. There are already fossils

14:45

in the time of dinosaurs. It's so

14:47

full of sulfur based compounds. Those

14:49

get aerosolized. And we know from some of our own

14:51

human activity, use. That these sulfur based

14:53

compounds when you put them into the atmosphere, they're really

14:55

good at reflecting sunlight back. And

14:58

after you have this heat pulse, after you have the fires that

15:00

dies down, you start to have this accredibly

15:02

quick global cooling. You have an impact

15:05

winter that drops temperatures around

15:07

the planet. Photosynthesis is on a

15:09

stop. We know this from some fossils in the ocean

15:11

where if you're a photosynthesizing algae, which is

15:13

one of the most important creatures on the planet,

15:16

they provide so much for oxygen, everything else,

15:18

they just disappear. You only have things

15:20

that are basically able to scavenge to,

15:22

like, make do on whatever

15:24

little morsels they can find.

15:27

And that goes for about three years. So

15:29

you have, like, this perfectly idyllic, you

15:32

know, for a dinosaur, cutaneous day, an

15:34

asteroid impact within twenty four hours.

15:37

It's so hellish that most

15:39

creatures of an extinct probably went extinct in this

15:41

interval. And then even if you survived that,

15:44

you had to deal with years

15:47

of basic scraping buying whatever you could possibly

15:49

find. And that's this extra extinction

15:52

filter. So this really was there's not a mass

15:54

extinction like it. All previous four that we

15:56

know about were caused by things like volcanic

15:58

activity or changes in oxygen levels. They took

16:00

tens tens of thousands of years to transpire.

16:03

This we're really talking about, like, the blink of

16:05

an

16:05

eye, that all of this happened, the world changed.

16:07

It's fascinating as you say twenty four hours

16:10

one day and Riley, so Do we think

16:12

therefore that the whole world was grid

16:14

basically became an oven in those twenty

16:16

four

16:16

hours? Or was it more centered around where

16:18

the asteroid actually hit? So far as

16:21

we're able to tell, the models suggest that this

16:23

was global. This wasn't just localized somewhere,

16:25

but all this debris basically got scattered.

16:28

So high into our atmosphere and spread so

16:30

far that they're coming down all over the planet. And

16:32

we've been able to verify this if you go to

16:34

New Zealand, if you go to Italy, if you go

16:37

to China. If you go to all these different places

16:39

around the world, you find

16:42

impact debris. You find little spirals of

16:44

glass and little bits of rock and

16:46

what we call shocked quartz. So quartz has been hit

16:48

so hard. It's actually kind of cracked on

16:51

the inside. So that was one of the ways

16:53

that this event was first identified. was

16:55

geologists looking at saying, like,

16:57

hey, we have this, like, impact layer. We wanna

16:59

try and figure out how quickly it formed.

17:02

And they started to realize this isn't just in

17:04

this one locality, this is global.

17:07

So even though, like, the

17:09

direct effects of the impact were very local,

17:12

the aftereffects sort of the how quickly

17:15

this asteroid was moving the angle at

17:17

which it hit the rock that it hit

17:19

all of these things played into it. And

17:21

that's what really gets me about this whole thing is

17:23

that it didn't have to be this way. We have impact

17:25

creators that are, in fact, larger. There's one

17:28

in Siberia called the Popeye Creator that was

17:30

made around fifty million years or so ago that

17:32

is not tied to any kind of mass

17:34

extinction whatsoever. So,

17:36

you know, we would treat it as obvious, you know, big rock strikes,

17:38

planet. There's gonna be a mass extinction. Most

17:40

of the time that's not true, most of the time life

17:42

on earth is outside of, like, the local area

17:45

that that impact would have affected has gone

17:47

on pretty much unimpeded. This is

17:49

the one time. This is the one

17:51

worst case scenario where everything that

17:53

could have possibly went

17:55

wrong. Went wrong. It's absolutely

17:57

extraordinary, Ryan. And before we go on to

17:59

the the longer after effects

18:01

the year you mentioned impact winter. But

18:03

from what you were saying there, dinosaurs,

18:06

you know, the acme creature on land

18:09

before then. It seems like

18:11

if they were on land, not underwalls, or any

18:13

of those places that are they creatures

18:15

most affected by this immediate

18:17

effect of the asteroid strike?

18:20

So we think of our non avian dinosaur

18:22

friends. Let's say non avian because, you know, dinosaurs

18:24

are still alive in the form of birds, so the ones that survive.

18:26

I'm not sure. We'll we'll talk about that. At

18:28

the time, non avian diners were they were

18:31

sort of the most I wanna say the most prominent

18:33

creatures in the landscape. We often talk about dominance,

18:35

so that doesn't really mean anything. That's just

18:37

something that we use to make them sound impressive. But

18:39

the fact is that they existed in sizes

18:41

from absolutely tiny to gigantically huge.

18:44

Share all these different roles and it's just everything else.

18:46

They were important creatures. They're sort of like the equivalent

18:48

of what mammals are today. And

18:51

of course, this basically wipes them out

18:53

entirely because with the exception

18:55

of maybe a few species that were able

18:57

to find refuge in burrows

18:59

that they were small enough or they'd made themselves

19:02

and they eventually still went extinct. There

19:04

wasn't anywhere for them to go. You know,

19:06

if you are transverse sex.

19:09

Let's say, well, you're not even the big ass. Let's say, you're, like,

19:11

thirty feet long and something

19:13

like six tons. You know, still a big animal.

19:16

You're not gonna dig something deep enough,

19:18

fast enough to escape

19:20

this. They didn't have any preexisting

19:22

adaptations to help them through, and that's what

19:25

made the difference for this you can't plan for

19:27

an event like this. It's really the lack

19:29

of the draw in terms of like what you do.

19:31

But I wanted to be clear that. The dinosaur were

19:33

literally that We lost them beyond

19:35

the beaked birds, but there are also mass

19:37

extinctions of mammals birds

19:40

and lizards and snakes. And amphibians

19:42

do really well and really only starting to

19:44

understand why that is. That's always been a big

19:46

mystery. And even in the oceans, you had almost

19:49

total ecosystem collapse. As

19:51

a result of this. So we lost

19:53

the ammonites and the moses swords and the

19:55

other marine reptiles. And even these clams

19:57

are, like, the size of a toilet seat called the

19:59

Rudesc disappear. And nobody talks

20:01

about them. always like that, you know, we could have had giant

20:04

clams, if not for this impact. So dinosaurs,

20:06

I think, were most effect in terms

20:09

of, like, most shaken up by this. They were

20:11

cut back incredibly severely. Whereas

20:13

for most other groups, they went through mass extinctions was

20:15

kind of a reshuffling. So, like for mammals,

20:18

marsupial mammals used to be much more prominent

20:20

around the world, especially in the northern hemisphere, they

20:23

became much less prominent afterwards and

20:25

gave or placental mammal relatives

20:27

and ancestors a shot to proliferate

20:29

through those spaces. So, yeah, I

20:31

think that's probably reason that we focus on dinosaurs

20:33

so much is that they were around for

20:35

so long. They survived the continent

20:38

shifting around. Changes in global

20:40

climate change. All these things they lived

20:42

through earth fantastic changes

20:45

for hundred and fifty million years.

20:47

And then in a day, they're basically

20:49

gone. That demands an answer. We want

20:51

to know why, like, as much as we might feel

20:53

directly for mammals or other things.

20:55

It's to look at these animals that we kind of

20:57

like you said, look at as the acme of these paragons

21:00

of success. And then it vanishes suddenly.

21:03

And this impact, this mass extinction, is

21:05

really showing us why, how that happens. Riley,

21:08

I mean, absolutely two minds at the moment, whether it's

21:10

continued the story. But I've got one question that

21:12

is my brain is just dying for me to ask

21:14

now. Which is you've mentioned borrowing already,

21:17

and these catastrophic twenty four

21:19

hours right at the start. So how

21:21

can a few inches centimeters of

21:24

soil save so

21:27

many of these smaller mammal like animals

21:29

in this first day compared

21:31

to those that don't have anywhere to borrow

21:33

into. Alright. So the secret

21:35

really is the soil or if you're

21:37

an ancient turtle or crocodile or something like

21:39

that, you know, even just a few inches or a few centimeters

21:42

of water can make a huge difference.

21:44

And as far as soil goes, that's because soil is

21:46

great acting as a buffer against heat.

21:48

We know this from modern forest fires. There are some forest

21:51

fires so intense that it kind of recreate

21:53

some of these conditions from sixty six million

21:55

years ago. And we know that,

21:58

you know, the moisture that's held in the soil

22:00

sort of what soil is made of, you know,

22:02

not just sort of particles of, like, rocks

22:04

and things have been ground up, all the organisms and

22:07

things in there. It's really good

22:09

at taking up heat and and acting

22:11

as a buffer. So, really, I think it was about ten

22:13

centimeters. It's really all it takes

22:15

to buffer the effects of, you

22:17

know, the equivalent of this heat pulse. So

22:20

you didn't have to go down very far. So

22:22

if you are a burning mammal, you don't

22:24

have to go far down. But there are also other organisms

22:26

like, you know, we know there are ancient turtles. And

22:28

crocodiles and even some dinosaurs borrowed.

22:31

And these animals didn't always just make

22:33

a bird and live their their whole lives. They'd make

22:35

them season after season to move place to place.

22:37

So, like, even though we're abandoned boroughs

22:39

or what we know from organisms today that sometimes

22:42

different species share. The same

22:44

burrow. And this was definitely like an any port in the

22:46

storm kind of moment, you know, during this heat pulse.

22:48

So if you were able to get underground that

22:51

quickly, you know, at least had the sort of refuge

22:53

wouldn't really be able to tell very much what was going

22:55

on on the surface above you. It acts

22:58

that well as a buffer. So that, I guess, is

23:00

the one actionable piece of advice if

23:02

you ever say, okay. You know, we're gonna have

23:04

an impact tomorrow. Break out the

23:06

shovel and start digging in the backyard because really that's

23:08

the best thing you can probably

23:09

do. House survived Armageddon.

23:12

Yeah. Yeah. Non dinosaur style.

23:18

Over on the warfare podcast history

23:20

here, we bring you brand new military

23:22

histories from around the world. Each

23:24

week, twice a week, we release new episodes

23:27

with world leading his Historians expert

23:29

policymakers and the veterans who

23:31

served from the greatest tanks

23:33

of the Second World

23:34

War. And so what are you actually trying get out of

23:36

you're trying to get maneuverability and you're trying to get

23:39

really big gun. You're tightening your pamphlet there

23:41

to dominate the battlefield primarily on the eastern

23:43

front and in the North Africa and all that sort of stuff.

23:45

But by this time, actually coming in in numbers.

23:47

That moment is already parked, through to new

23:49

histories that help us understand current

23:51

conflicts.

23:52

Any invader, any attack, or any adversary,

23:55

will ploit gaps within society.

23:57

It was true then. It's true today, but

23:59

the fans signaled that they were united, and

24:01

I think that's what the Ukrainians should

24:03

signal today too.

24:05

Subscribe to warfare from a history hit wherever

24:07

you get your podcast and join us

24:09

on the front lines of military history.

24:21

Friday. Okay. Let's continue with the story then.

24:23

So we've got past this first day. It's the first

24:25

few days. Temperature decreases if

24:28

I'm

24:28

correct, and you've mentioned a word already

24:30

that impact winter. So what

24:32

is this? Yeah. Peckelter here's

24:34

this event that's specifically tied

24:37

to the kind of rock that the asteroid

24:39

struck. And this

24:41

for long time is thought to be the main killing mechanism.

24:43

We didn't know that the heat pulse until relatively

24:46

recently. During the 1980s when this

24:48

hypothesis was first coming forward, and there

24:50

was a lot debate about it. this was sort of the end

24:52

of the cold war, and it was very much into

24:54

worries about nuclear winter. So if you think

24:56

about sort of like fears over nuclear winter, it's

24:58

kind of like that naturally naturally caused.

25:00

So what happened was you had all these sulfur based

25:02

compounds that went out to the atmosphere, they're

25:04

reflecting sunlight back. Like enough to

25:07

send enough sunlight back that photosynthesis on

25:09

our planet was reduced by about twenty

25:12

percent or so. That doesn't sound

25:14

like, you know, it's it's purely significant,

25:16

but it doesn't sound like it would be lethal. But

25:18

the thing is, Oliver's ecosystems are

25:21

basically based on photosynthesis. So

25:23

if you don't have plants to eat,

25:25

then you're not really gonna have very many insects. You're gonna

25:28

have things that eat those insects. It's really getting

25:30

bind what we can and it seems to dovetail with some

25:32

other evidence that we've found or at

25:34

least other hypotheses about why

25:36

certain creatures survived. Another died out.

25:38

Just to give an example of this, you know, birds

25:40

are living dinosaurs. But we know during the

25:42

Cretaceous, you know, the day before the asteroid

25:44

struck. We had bird like raptors.

25:47

So basically, you know, things like the lost raptor covered

25:49

feathers. They had teeth and claws. They also

25:51

had toothbirds that ate little

25:53

lizards and insects and things like that. And we had beechbirds

25:56

that specialize in vegetation and seeds

25:58

and that sort of thing. So during

26:00

this impact winter, we don't really have plant material,

26:02

and you don't really have very much prey

26:05

to go hunt. The carnivorous species disappear

26:07

the tooth birds and the Raptor like

26:09

dinosaurs, they go extinct. But

26:11

beechbirds make it through because they had

26:13

already adapted to shift to basically

26:15

underground storage organs. You know, seeds,

26:18

nuts, things like that. They're in the seed bank that

26:20

are preserved in the soil, so they can get enough

26:22

of those things to make it through.

26:24

So even though this is, you know, it

26:26

might seem like not all that long. It's three

26:29

years compared to some of these other mass extinction events

26:31

that took tens of thousands of years

26:33

to play out. That is still an excruciating

26:36

long time. If you're an organism trying to, like, make

26:38

your way through to to continue to survive and

26:40

reproduce and all these things

26:42

that life does. When we look in the

26:44

oceans, the oceans like, we're

26:46

so close to basically

26:48

being thrown back five hundred million years. By

26:50

that, I mean, like, going back to almost, like, a

26:53

a state where only single celled organisms

26:56

live there. We can tell this. Because

26:58

there are these little things called cocolates.

27:01

They're basically algae. There's these little clumps

27:03

of algae that kind of make these circular

27:06

structures. And before the mass extinction,

27:08

you have ones that photosynthesize. And you also have

27:10

ones that are able to eat organic matter. They're

27:12

called mix of truth. So they can photosynthesize But

27:14

if they can't photosynthesize for some reason,

27:16

they can find other food. After the extinction,

27:19

you only find the mix of the trosts. The photosynthetic

27:21

ones entirely disappear for

27:24

a time. So if those algae

27:26

basically hadn't evolved this, like,

27:28

not carnivorous isn't the right word. You know,

27:30

these algae they're able to feed on other

27:32

organic matter hadn't existed, then the

27:34

oceans would entirely one hundred

27:36

percent collapse and would've been worth

27:39

even than it was. So we came that

27:41

close to having basically the reset

27:43

button pressed on the planet.

27:45

So it was three years of really scraping

27:48

by however life possibly could

27:50

for we're still learning about what happened.

27:52

In that interval, it's hard to be that precise

27:54

when we're looking this far back in time.

27:57

But that picture is starting to come into view.

27:59

And it it seems a lot more dire than we

28:01

thought. There'd be a lot of, like, cartoons I remember seeing as

28:03

kid of sort of, dynafores wandering around

28:05

this darkened and kinda ashes landscape,

28:07

and that's the sort of, you know, caricature image.

28:10

The reality of it was like, this

28:13

was a a time of great struggle. Really,

28:15

if you're able to make it through that first day,

28:17

then you had three years of really hanging on however

28:19

you

28:20

could. mean, it's interesting that you mentioned

28:22

just three years. So is it

28:24

almost as if you get through those three years?

28:26

Is that almost a moment when it

28:29

I guess, could you say a recovery starts?

28:31

Or does it take much

28:32

longer? Yeah. That's a great question. Now,

28:34

like, what does recovery look like? We talk

28:36

about recovery would like to think, you know, sixty six

28:38

million years later, the life has recovered.

28:40

And yet, we don't have anything like

28:43

a twenty ton herbivore wondering

28:46

around. So, like, how have we fully recovered

28:48

yet? It's something life is life is certainly

28:50

different. But in terms of ecosystem

28:52

complexity, what we

28:53

were talking about before where you have, you

28:55

know, your photosynthesizers and the things that eat

28:57

them, the things that eat those animals and so on

28:59

and so forth. That took

29:02

at least a million years after

29:04

impact. You start to see the beginnings of

29:06

recovery after the impact winter. Guys

29:08

away, but still takes time. Really, you you

29:10

have what we call disaster tax. So these

29:12

animals and organisms and plants that

29:15

do well in disturbed environments. So

29:18

for example, on a hundred thousand years,

29:20

more or less, after impact, you

29:22

see fern pollen appearing

29:24

great amounts all over the world. You look at the

29:27

rocks like basically just above the impact

29:29

layer. And this has been referred to as

29:31

the fern spike. And ferns, we know this

29:33

from places like where volcanoes are at. Today,

29:36

they do very well in places that have recently

29:38

been shaken up in some way, or

29:41

that ground has been disturbed. And

29:43

the way that they reproduce in those very dependent

29:46

on water and moisture, they do

29:48

really well in those. So that

29:50

was kind of the beginning of sort of life

29:52

beginning to really reseat and

29:54

build up these forests so that by a

29:56

million years after you have

29:59

forest growing in ways that they never did

30:01

before. It's different. Than it was.

30:04

But you can start to say, okay, life seems

30:06

to be not just even settling in,

30:08

but evolving in different ways, you know,

30:10

mammals, for example, by that time. We're

30:12

getting big so quickly. So

30:14

you'd have a mammal that was the size

30:16

of German shepherd. But with

30:18

the brain, the size of its cretaceous, ancestors

30:21

so that body size just explodes during

30:23

this interval. That brain size and these

30:25

other sort of traits and adaptations haven't

30:27

caught up. Just yet. But we can look

30:30

at that and say, okay, this is the beginning of life really

30:32

starting to proliferate and fill these

30:34

ecosystems and do something different than

30:36

before.

30:37

Really for me is an average joke box. It still absolutely

30:39

blows my minds that species such

30:41

as mammals and amphibians. You know, Crocs,

30:44

they were able to survive that incredibly catastrophic

30:47

tumultuous period, which as he mentioned,

30:49

was a hundred thousand years or more.

30:52

And then are able to start thriving

30:54

in this new world where the dinosaurs

30:56

are and those huge reptiles in the sea

30:58

are no longer there. It's strange.

31:01

Right? Strange thinking about this world that's

31:03

so full of possibility. Really?

31:05

One of the things I love learning about in writing this

31:07

and I really want to drive home. Was

31:10

the interconnections between all this. We often

31:12

focus on, like, a singular animal

31:14

or icon. And what what is it doing? We

31:16

try and understand the whole ecosystem through

31:19

its adaptations and its perspectives and really

31:21

it's all these interconnections. So we think about

31:23

forests, for example, that is a really critical

31:26

part of the story because when

31:28

animals like triceratops and edmontosaurus were

31:30

around, they're not just eating plants.

31:33

They're trampling things down depending on where they

31:35

walk. They are spreading seeds

31:37

in their dungas they go about their business. They

31:39

are basically shaping the landscape.

31:41

These are what we call mega herbivores today. I think

31:44

the equivalents of elephant and drafts

31:46

and things like that, that not only,

31:48

you know, have their place in the ecosystem, but they change

31:50

it, and they make it open. So

31:53

even though the plants were very, very different, if you can

31:55

imagine sort of, you know, almost any documentary you've

31:57

seen you know, Eastern Africa and sort of the

31:59

grasslands and stuff there, how it's kind of these

32:01

stands trees and big spaces in

32:03

between them. That's kind of what dinosaur

32:05

created forest would somewhat look

32:07

like. But then after the impact, you don't

32:10

have these big animals. Eating so

32:12

much and pushing trees over and trampling

32:14

the ground down. So forest grow denser.

32:16

And when you have that, when you have this dense

32:18

canopy kind of environment, you have

32:20

a lot more sort of ecosystem space

32:23

per, you know, square kilometer. So you

32:25

have, you know, organisms that are gonna burrow

32:27

into the soil and then those that live on the surface

32:30

and those that live on the trunk of the tree and at different

32:32

levels in the canopy. So for any given

32:34

space, you have a lot more different

32:36

habitats. And that's what really underwrites

32:39

this evolutionary explosion that we see,

32:41

you know, about a million years or so after

32:43

the impact. If that if

32:45

if there's more room to do something

32:47

different, to evolve in a new way, you're having

32:49

a hard time, you know, getting the food you

32:51

require, on the surface of the ground.

32:53

Maybe you start climbing trees if you're able to

32:56

do that. And, like, I don't mean to make this sound like

32:58

one market, like, these creatures are siding to do

33:00

it or something somehow. But through all

33:02

this competition for this incredibly rich

33:04

space, all these organisms are kinda

33:06

nudged into doing new things that

33:09

they didn't do before. And

33:11

it really allows us, you know, mammals and

33:13

birds and all these other creatures to come

33:15

forward. One of the things I love about Crocs for example

33:17

is, like, they look like they you know,

33:19

they're they're ancient. You know, they haven't been doing anything

33:22

new. But what we understand from some

33:24

newer research is that they

33:26

evolve incredibly quickly, they just keep doing

33:28

the same thing. It's like when you have have

33:30

your favorite takeaway place and you order the same

33:32

things each time on those rocks you're

33:34

doing that in evolutionary sense. Where

33:37

instead of doing something different or becoming dinosaur

33:39

like, you're just doing the semi aquatic ambush

33:41

predator thing over and over again.

33:44

So you know, even the organisms

33:46

that make it through, they're not just doing

33:48

it because they're kind of stalwart in their

33:51

niche or their adaptations. They're

33:53

still responding to all this change and often

33:55

evolving very quickly to meet these new

33:57

conditions. I've got to ask

33:58

this, how do we know all of this? Yes.

34:01

It really comes together from a lot of different

34:03

lines of information and this really in

34:05

the past five years. We have

34:07

learned so much more than possible. Like,

34:09

the book that I wrote, I probably wouldn't have been

34:11

able to write it with as much detail if I

34:13

tried to do so maybe even five years

34:15

ago. So one of the most

34:17

critical places where a lot of this information comes

34:20

from, there's spot outside Denver, Colorado

34:22

called Corral Bluff. And it's

34:24

a great place because you not

34:26

only have fossils of the animals that come in

34:28

these concretions is kind of neat. If you imagine kind

34:30

of like a geoder, almost like a boulder, have

34:33

to crack them open and prep away this really

34:35

hard rock to see them. But you have mammals

34:37

and turtles and rocks and things like that, but also

34:39

plants and also it's really well constrained

34:41

in time. So we're able to get good dates from

34:43

it. To get a good date in paleontology

34:46

is phenomenal. Because then you finally said that, like, this

34:49

was happening at this time, and we're not doing,

34:51

like, the more give or take, you know, a million years

34:53

or five million years, which is a long span of time.

34:55

So at Carell Bluffs, we're

34:57

able to see how life is responding

35:00

about a hundred thousand years after

35:02

impact, about a million years after impact

35:04

in the

35:05

same place, basically in the same

35:07

geographic spot. Where

35:09

all these changes are unfolding. And

35:11

as discoveries like that, this was something that

35:13

someone had actually found long ago, and, you know, paleontologists

35:16

only recently went back to have another look.

35:18

So it's things like that, the continued

35:21

sort of research and modeling of what would

35:23

happen, like, as we get a better understanding

35:25

of know, impact through

35:28

history and what happens and the speeds

35:30

and forces them better constrained like what this asteroid

35:32

was doing and how it struck planet. All these

35:34

little pieces come together, and that's what really the book

35:36

is. The reference list is really a synthesis

35:39

of all these little bits and pieces. That

35:41

are just starting to come together,

35:44

that we finally have these sort of

35:46

computing power and discoveries and

35:48

the curiosity. To look at this in a

35:50

different way. It used to be that we took the extinction

35:52

of the non avian dinosaurs as a given.

35:55

Why wouldn't they? They're big, weird, lizard things.

35:57

Once we realized that this was something

36:00

exceptional, then we could

36:02

start to ask these questions and

36:04

serve refine. What we thought. And it's really

36:06

been relatively new. The impact hypothesis came

36:08

out in nineteen eighty. And

36:10

I was born in nineteen eighty three, so this really

36:13

has only been in my lifetime that we even

36:15

knew that this happened much less

36:17

getting the clarity that we do now. So I am really

36:19

curious to see forty years from now,

36:21

if I'm lucky to be around to see it, like, how

36:23

our understanding will have changed. So

36:25

that's something I tried to be transparent about in the

36:27

book. This is all sort of the best information that we have

36:29

right

36:30

now. I'm probably wrong about some of

36:32

it, and I'm gonna be happy to find out what actually

36:34

happened when we get to that point. It'd

36:36

both be very, very exciting for the future,

36:38

indeed, therefore. I mean, I love going

36:41

to one particular case study now. You mentioned it

36:43

earlier. I could ask more about mammals. I could ask more about

36:45

crocodiles. I want to ask about amphibians. Why

36:48

do amphibians

36:50

survive the impact so well and

36:52

then go on to thrive?

36:54

Yeah, this is something that we haven't really

36:56

been able to get our heads around. It doesn't seem

36:58

to make sense. You have these ectothermic

37:01

organisms. They get they get their, you know, temperature

37:03

regulation. They regulate their body temperature

37:06

based upon the environment they're in and they go

37:08

through incredible heat and then incredible cold.

37:10

How does this make sense? The acid rain was

37:13

thought to play a role in this because a lot of those sulfur

37:15

based compounds, they also create acid rain that probably

37:17

has something to do with why fossils are so difficult

37:19

to find. From this interval that a lot

37:22

of them were kinda eaten away by

37:24

the acid rain that, like, eventually came

37:26

back out of the atmosphere. But

37:29

in terms of amphibians specifically, there was just

37:31

a paper that came out about body size,

37:33

how, like, if you're very very small in your amphibian

37:35

or you're very very large, you're

37:37

much more affected by environmental changes.

37:41

Things like, for example, if you're a very, very small

37:43

frog, a slight change in

37:45

the temperature of your environment, make it

37:47

very much more difficult to regulate

37:49

your body heat, to do things like reproduce, and

37:52

and all that sort of stuff that a frac would normally

37:54

do. Same thing if you're really, really big, it can be

37:56

very difficult to lose excess

37:58

heat or to warm up if things get too cold.

38:01

Whereas if you're kind of in the middle, those

38:03

amphibians seem to do a little bit better,

38:05

but that's just really describing a pattern. That's not

38:07

really telling us precisely why it's more just like these

38:09

seem to do a bit better. And it's

38:11

possible that for the acid rain component of

38:13

this, like, number one, and it wasn't as much of

38:15

an amphibian killer as we previously believed.

38:18

And also there are like a lot of ponds

38:20

and water sources that had limestone

38:22

basically as their foundation. And if you

38:24

have that, the acidity

38:27

of the rain would react with

38:29

the calcium carbonate in that

38:31

limestone and basically the the rock acted

38:33

as a buffer. It reduced the acidity.

38:36

So those water sources didn't become

38:39

as hostile to amphibians as we previously

38:41

believed. That's really the main outline.

38:43

That's something that, like, it really has only

38:45

been in the past year or

38:47

so. That this is starting to come

38:49

into to focus. I think one

38:51

of the that question of, why

38:54

do you these things like

38:57

bony fish and rocks and amphibians

38:59

do so well? When our big charismatic

39:01

favorite creatures don't do very well.

39:04

And there's there might be something we don't know

39:06

just to end on on, you

39:08

know, that question this particular point. I remember

39:10

seeing a presentation number years ago. Just

39:12

looking at, like, each of the species

39:14

that makes it through. How long are

39:17

they around? Just in evolutionary terms,

39:19

what is the turnover for it? So

39:21

a dinosaur species on land. Most

39:24

organisms on land are really only around

39:26

for a million years, two million years before

39:28

they either evolve into something else or they go entirely

39:30

extinct. Organisms in freshwater

39:33

environments, you can go back ten million

39:35

years before the impact and find

39:37

the same species of crocodile and

39:39

herd fertile and thick and things like

39:41

that. So there's something about those environments

39:45

that they're stable enough, or the

39:47

conditions are stable enough, or organisms have evolved

39:49

in such away that there's always a kind of place for

39:51

them, that they have a longer staying power

39:53

through all these shifts. They're kind of adapted to

39:56

deal with environmental turbulence. In

39:58

the way that organisms on land are almost

40:00

constantly changing to

40:02

try and keep up with all these little

40:04

shifts. And that might have something to do with this

40:06

pattern. Let me see. Well, it's supposed to be very

40:08

exciting for paleontologists in the future

40:10

and budding paleontologists and people like

40:12

yourself Friday looking to learn

40:15

more and more about this incredible past

40:17

past, very, very, very distant past.

40:19

I mean, to wrap it all up now, it is so

40:21

extraordinary to talk about this topic because

40:23

we do as hinsed out at the start.

40:25

We always focus on the catastrophe, you know,

40:27

seventy five percent roughly of life is wiped

40:29

out with the meteorite, but it's

40:31

the recovery and the resilience of

40:33

the earth. Which is equally if

40:36

not more astonishing, isn't it? Oh,

40:37

absolutely. I mean, the fact that

40:40

since life originated, on earth. So

40:42

far as I know, barring any, like, early extensions that

40:44

we wouldn't know about. But basically, if we go back to the last common

40:46

ancestor of all life on earth, you know, over

40:48

three and a half billion years ago, life has never

40:50

disappeared. Since then. It has always

40:53

made it through. It's been battered.

40:55

It's been cut back. It's had to deal with extreme

40:57

circumstances, but it has always

41:00

made it through somehow.

41:02

And I found a lot of personal meaning in that. I talked

41:04

about this a bit in conclusion where during the

41:06

time I was writing this book, I was going through a lot of personal

41:08

changes and some big shakeups. In

41:10

my own life. And I took a lot of solace

41:13

in the idea that, like, after

41:15

going through what felt like very personal kind of

41:17

asteroid impact in a way in the life that I

41:19

had, being more or less swept

41:21

away and starting something new, especially

41:23

through transition. It was

41:26

focusing on that sort of resilience. Life

41:28

can grow in a different way, but it's not lesser.

41:30

It's not something that has to

41:32

compete with what existed before.

41:35

It's amazing that it can exist

41:38

and grow in different way. And I

41:40

love that on the geological timescale. This is

41:42

really that story. We are here. Because

41:44

of this. And I love the fact that our ancestors

41:47

were there, and I don't just mean that in a general sense.

41:49

You know, there's this animal might not be a direct

41:51

ancestor of ours, but the first primates.

41:54

Or around the same time as t rex. So when

41:56

the asteroid struck, our

41:58

primate forebearers who

42:00

had just evolved really that were these new

42:03

things on the planet made it through that,

42:05

whereas our favorite dinosaurs didn't. And if it's

42:07

things that did just a little different, the primate

42:09

story, our story would have been snuffed out

42:11

before it even started, and yet we're here.

42:13

And I think that's fantastic. And I think

42:16

rather than the loss, especially through

42:18

all the various stresses and things like,

42:20

you know, our world has been through recently, A

42:22

story of resilience like this is a really

42:24

important one to

42:25

tell. Well, Brady, that's a lovely

42:28

comment to finish the podcast episode

42:30

on last but certainly not least. Your

42:33

book on this topic, it is called

42:35

Riley, the last days of the dinosaurs.

42:37

Well, fantastic, Riley. It just goes me to say

42:39

absolute pleasure, and thank you so much for taking the time

42:41

to come forecast today. This

42:42

has been wonderful, Chestnut. Thank you.

42:48

Well, there you go. There was Riley Black

42:50

taking us back some sixth six

42:52

million years to the worst day in

42:55

the story of life on earth.

42:57

The extinction of the dinosaurs, the

42:59

asteroid's collision with the Earth,

43:01

and how the planets recovered

43:04

in the wake of

43:06

this massive catastrophe.

43:09

I hope you enjoyed the episode today.

43:11

Last thing from me, you know what I'm gonna say. Well, if

43:13

you're enjoying the ancients and you want to help

43:15

us out, you can do something very easy, very

43:17

simple. Just leave us a lovely rating on

43:19

Apple Podcasts and spotify wherever

43:22

you get your podcast from, it greatly

43:24

helps us as we continue to

43:26

share these amazing stories with our distance

43:28

past with you. And with as many people

43:30

as possible. Have you got any thoughts

43:33

on the ancients podcast, what you love about it,

43:35

but also ways you think that we can improve. We can

43:37

be better in the future. Please do also drop

43:39

us a comment

43:40

too. I love new

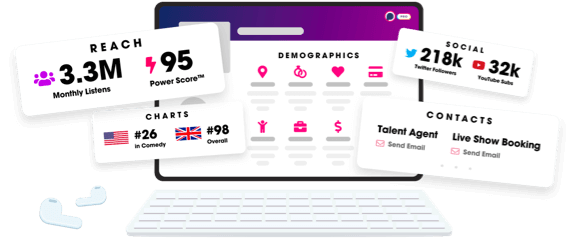

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us