Episode Transcript

Transcripts are displayed as originally observed. Some content, including advertisements may have changed.

Use Ctrl + F to search

0:00

This episode is brought to you by Progressive.

0:02

Are you driving your car or doing laundry

0:04

right now? Podcasts go best when they're bundled

0:07

with another activity. Like Progressive Home

0:09

and Auto policies, they're best when they're

0:11

bundled too. Having these two policies together

0:13

makes insurance easier and could help you

0:15

save. Customers who save by switching their

0:17

home and car insurance to Progressive save

0:20

nearly $800 on average. Quote

0:23

a home and car bundle today at

0:25

progressive.com. Progressive Casualty Insurance

0:27

Company and Affiliates. National average 12

0:30

month savings of $793 by

0:32

new customers surveyed who saved with Progressive between June

0:34

2021 and May 2022. Potential

0:38

savings will vary. Ever

0:41

wondered how artificial intelligence or 3D printing

0:43

is used to solve medical problems? Or

0:46

how medical research is discovering new ways

0:48

to slow or stop medical conditions? We

0:50

used to think of as untreatable. Listen

0:53

to Tomorrow's Cure where host Kathy

0:55

Wurzer interviews experts from Mayo Clinic

0:58

and other renowned organizations such as

1:00

Cleveland Clinic, Johns Hopkins Hospital, or

1:02

the Veteran Health Administration. Get

1:05

a glimpse into these brilliant minds as

1:07

they share how they use innovative thinking

1:09

in their pursuit of answers for patients.

1:11

What they describe may sound futuristic, but

1:14

listen and you will find out

1:16

Tomorrow's Cure is already here. Find

1:19

Tomorrow's Cure wherever you get your podcasts.

1:23

I thought that's okay. If you're good enough,

1:25

you will overcome them with your great discovery and

1:28

then nobody will question you. And

1:30

I was wrong. It took

1:32

me 15 years to be certain that all

1:34

other women were discriminated against and I

1:36

still couldn't conclude it for myself. Took

1:39

another five, so it took 20 years. And

1:42

I got to say that the moment I realized

1:44

it was the worst moment of the whole thing.

1:47

You realized you'd been fooling yourself in

1:49

a way that nobody had ever seen

1:51

you as a full participant in

1:53

this system that you loved and are giving your life

1:56

to in a way and felt

1:58

was your life. people

2:00

saw you somehow differently. I'm

2:04

Katie Haffner. Welcome to WAST

2:07

Women of Science Conversations, where

2:10

we talk with people who have

2:12

discovered and celebrated female scientists in

2:14

books, poetry, film, and

2:17

the visual arts. Today

2:19

we're discussing the book, The

2:21

Exceptions, Nancy Hopkins, MIT,

2:24

and the Fight for Women in

2:26

Science, by Cade Zurnicki.

2:29

The book tells the story of Nancy Hopkins,

2:32

a molecular biologist who discovered her love of

2:34

science at 19 in 1963. She

2:39

earned her PhD at Harvard, trained

2:41

with two pioneers in the field,

2:44

and in the 1970s and 80s, she

2:47

made big contributions to

2:49

cancer genetics, broadening our

2:51

understanding of retroviruses, enhancers,

2:54

and their role in cancer biology. Later,

2:57

in 1989, Nancy changed her focus to zebrafish, which

3:03

allowed her to ask and answer

3:05

questions about genetics and development. And

3:08

yet, for all

3:10

those achievements, Nancy faced significant

3:13

challenges. Throughout her

3:15

career, she was often sidelined by

3:17

her male colleagues. By the

3:20

1990s, she began to fight

3:22

against the disparities, and

3:24

she did that with the same precision

3:26

with which she conducted her research. She

3:29

focused on gathering data, and

3:32

she went so far as to measure

3:34

by hand the size of her lab

3:36

and those of her male peers. And

3:39

when she realized that other female

3:41

faculty members at MIT were

3:43

encountering obstacles not unlike hers,

3:46

she led their fight for gender equity. Finally,

3:49

in 1996, a committee which Nancy chaired submitted

3:54

a landmark report documenting widespread

3:57

discrimination against female faculty at

3:59

MIT. We're talking

4:01

today with Kate Cernicki, who was at the Boston

4:03

Globe in 1999 and was the

4:07

first to report about Nancy's fight. Kate's

4:10

now a reporter at the New York Times, and

4:13

joining her is Nancy Hopkins herself.

4:16

Hosting the conversation is Juliana

4:18

Lemure. She's a

4:20

scientist by training with a PhD

4:23

in molecular biology and microbiology. She

4:26

now works in science communication and

4:28

is the deputy editor-in-chief at

4:31

Genetic, Engineering, and Biotechnology

4:33

News, or GEN. Hi,

4:37

I'm Juliana Lemure, and I'm so excited to

4:39

chat today with Nancy Hopkins and Kate Cernicki.

4:42

Kate, let me start with you. So

4:44

the book is about Nancy and the

4:47

fight for women in science, but you

4:49

actually start the story much earlier with

4:51

Nancy's childhood in New York City and

4:53

her journey from high school

4:55

to college at Radcliffe. Why

4:58

did you feel it was important to retrace so

5:00

much of her early life before we get to

5:02

the big headlines? Oh,

5:05

it's a good question. You know, first of

5:07

all, Nancy is such a compelling character, so I wanted to

5:09

tell as much as possible about her.

5:11

I think when I broke the

5:13

story in 1999 for the Globe, the

5:16

women at MIT were talking about unconscious bias, which was

5:18

a new idea at the time. But by the time

5:20

I came back to write the book and I started

5:22

reporting it in 2018, people had

5:25

really heard about unconscious bias and in many cases kind

5:27

of dismissed it and thought it didn't really happen or

5:29

it wasn't really a thing. So I

5:31

felt that to tell the story and to show

5:33

people how it works and

5:35

the toll it takes on women or people,

5:38

you had to tell this very personal story about

5:40

someone. So I wanted people to... I mean, I

5:42

sort of fell in love with the character of Nancy too, but

5:44

I wanted people to understand where she

5:47

came from. I also think there's so much

5:49

about Nancy's childhood that tells who

5:51

she is later on. For instance, there's

5:53

a story about how the

5:55

switchboard operator in the apartment building where she grew up

5:57

got very frustrated one night because... because all the girls

5:59

from her private school, from Spence, would be calling Nancy

6:02

asking for math homework help. And she had to take

6:04

like 34 messages from all the girls in the class

6:06

who wanted Nancy to do their math homework. When

6:09

I mentioned this to my book editor, she said that's

6:11

such a generous impulse. And I think there was so

6:13

much about her childhood that went to Nancy's generosity, but

6:15

also her determination that she had to do the right

6:18

thing. So for instance, when she gets

6:20

caught doing the math homework, the teacher asks her about it

6:22

and she lies about it and she feels terrible that she's

6:24

lied and she goes back and she has to tell the

6:26

truth the next morning, which I think again, just goes to

6:28

the kind of character we're dealing with. Nancy,

6:31

and now I'm gonna turn to you,

6:34

why you persisted for so long in

6:36

science after so many challenges. Can you

6:39

tell us a little bit about when

6:42

you first fell in love with science and

6:44

what it is about science that you love

6:46

so much? Wow,

6:48

what a question. What a wonderful question.

6:51

Listening to both of you does remind me of

6:53

these things, which no one doesn't think about very

6:55

often. I still remember those

6:58

girls who didn't love math

7:01

the way I did and I mean, oh my

7:03

gosh, think what they were missing. I

7:05

know I always felt, solving math problems

7:07

was a little bit like eating candy,

7:09

something about it. It was so rewarding.

7:12

It was just such pleasure to do it. And

7:15

I thought, oh, once they see this,

7:17

they're gonna enjoy it too. So the

7:20

science itself, yeah. I

7:22

have asked myself this question, why did you stick it

7:24

out so long? And it was, you

7:26

captured it. I think that's a tribute to Kate. I

7:29

think she then captured. People who

7:31

love science really love it.

7:34

Then to this day, I've

7:37

looked hard for other things that

7:39

are as exciting or as

7:42

mind blowing as science. But at the end

7:44

of the day, it's almost a

7:47

belief system. And

7:49

it just really appealed. It's mine.

7:51

It's the one that works for me. When

7:53

I had the problems, well, first

7:56

I thought the privilege of being able

7:58

to be a scientist. at

8:00

a place like Harvard or MIT where I worked

8:02

in Cold Spring. I

8:04

mean, I realized how incredibly fortunate

8:06

anyone was who got to do that.

8:09

And so I used to think, god, what if you've been

8:11

born in some place where there isn't such science? You

8:14

wouldn't even know it existed. And so to be

8:16

able to be there, I felt, was a real

8:18

privilege. So I felt sorry for everybody else who

8:20

wasn't there. But tell the

8:23

story about how you fell in love with science, because

8:25

I think it is a real moment for you. And

8:27

I think the passion of that moment and

8:29

all that science was going to uncover for

8:31

you, I think, when you talk about that

8:33

lecture at Radcliffe. Oh, well, yes. I had

8:35

liked science all the way through from school.

8:37

But I had then

8:40

gone to college in an era when

8:42

women were expected to get a very

8:44

good education, meet their husband when they

8:46

were in college, marry soon after, have

8:48

children, and work, perhaps, but not have

8:51

such a concentrated career as a man

8:53

would in that generation at

8:55

that time. And

8:58

I think a lot of young people who go to

9:00

college, you're suddenly free thinking about your life and what

9:02

you're going to do with your life. And

9:05

I wasn't completely convinced that this was the

9:08

right path, even for me. Somehow,

9:10

was I going to be happy living in the suburbs with

9:13

two children and a dog? I don't know. And

9:15

so I thought, maybe I should go to medical school. I

9:18

had all the requirements done except biology. I signed

9:20

up for the thing. And I walk innocently into

9:22

this class. And I hear a

9:25

lecture by James D. Watson, the

9:27

man who discovered the structure of DNA. And

9:29

I walk in as one person. And I walk

9:31

out as a different person. And that is the

9:34

meaning of life. He's just told us the

9:36

secret of life. And for me, it was the

9:38

meaning of my own life. And suddenly,

9:40

everything fell into place. Oh, whoa,

9:44

these molecular biologists, they're going to

9:47

figure out everything about

9:49

living creatures, including humans, who are

9:51

going to understand diseases, and why

9:54

people are the way they are, and how the world works.

9:57

It was a real bombshell. I

10:00

think, yeah, scientists do just get bitten by a bug,

10:02

don't we? We do. I mean,

10:04

I suppose people do for many things. I

10:06

think some people, it's music. Some people,

10:08

it's playing tennis, whatever it is.

10:11

But for me, it was just one moment

10:13

like that, one hour. Wow,

10:16

that's it, done. So

10:19

let's talk a little bit about some

10:21

of the challenges that you did face

10:24

during your career. For

10:26

example, and for people who read the

10:28

book, no, during your recommendation for tenure,

10:30

despite being your department's top choice, your

10:33

name was surreptitiously moved down the list

10:35

at the request of a prominent colleague.

10:38

You were excluded from departmental meetings, did not

10:41

receive the same opportunities to apply for funding,

10:43

or they were actively hidden from you.

10:46

You had the credit for a discovery

10:49

stolen by a male scientist, and

10:51

you were not given the same amount of

10:53

lab space as your colleagues. So

10:56

looking at some of these, was

10:58

there one that was more

11:01

difficult for you, or the

11:03

biggest one that was the turning point

11:05

for you? That also

11:07

is a very interesting question, and a bit hard

11:09

answer, because I think it

11:13

is the cumulative impact of

11:15

these things over years that

11:17

turned me into an activist for sure. I

11:19

think for each one of them, you try

11:22

to find a solution when you

11:24

can't. You navigate around it, you keep

11:26

going, you find another one, another thing

11:28

happens, you do the same thing. But

11:31

I think the other part of it is, when I

11:33

look back, people say, why did it take you so

11:35

long to figure this out? Everybody else knew what was

11:38

your problem. It was a belief

11:40

that science really is

11:42

a meritocracy. And

11:44

if you make an important enough discovery,

11:46

it won't matter what other people think

11:48

of you or how they treat you. You

11:51

will be acknowledged for what you

11:53

do. It's just the nature of science. And

11:57

I think that belief is so

11:59

strongly. embedded in

12:02

the occupation culturally.

12:05

And I think the other thing was that

12:07

yes, if you complained, other

12:10

people who felt as I did would

12:12

see you as a whiner and also

12:14

as somebody who wasn't good enough, because if you were good enough,

12:16

you wouldn't have to complain, you would just get on with it.

12:19

So you were silenced and

12:21

also very insecure in whether

12:24

you were right in your judgment of whether it

12:26

was fair, so you were just going to say,

12:28

well, did that really happen because I was a

12:30

woman? But finally, it took me 20 years, it

12:34

took me 15 years to be certain that

12:36

all other women were discriminated against and

12:38

I still couldn't conclude it for myself.

12:41

Took another five, so it took 20 years. And

12:43

I gotta say that the moment I realized

12:45

it was the worst moment of the whole

12:47

thing. You realize you'd

12:50

been fooling yourself in a way nobody

12:52

had ever seen you as

12:54

a full participant in this system that you loved

12:56

and are giving your life to in a way and

12:59

felt was your life, that

13:01

people saw you somehow differently. And

13:04

so that moment, I think people resisted.

13:06

I think it's easier to think that

13:08

maybe you really aren't good enough than

13:10

it is to think that people don't

13:13

see you fairly. If it's really something

13:15

as deep as they don't see women

13:17

the same way they see their

13:19

male colleagues, there's nothing you can do

13:21

about it. Right, you give

13:23

up a little control over your own destiny to say,

13:25

oh, it's just the system. Whereas

13:27

if you believe it's the meritocracy, you can just keep pushing

13:29

on, which is what I think most women did. Everybody's

13:32

different, you know, what is it that bothers you?

13:34

For me, it was the realization that, oh, they

13:37

never really saw me as one of them. That

13:40

was the one that was a killer. But

13:43

I became an activist because I

13:46

ran out of energy to try

13:48

to leap over one more problem and just keep

13:50

going. I just couldn't do it any longer. I

13:52

just ran out of energy. And

13:55

it was so ridiculous. And this was the

13:57

thing about teaching a class. I've been told

13:59

that I couldn't. teach undergraduates because

14:02

MIT students didn't believe

14:04

scientific information spoken by a woman.

14:07

And so, and I said, well,

14:09

of course everyone knows that. I had accepted

14:11

it as normal because as soon

14:13

as somebody said it, I realized, of course it's true. I

14:16

was able to see that women were

14:18

so under respected that students couldn't

14:21

respect them enough. And

14:23

so they were afraid to put an important cause

14:25

into the hands of a woman for fear the

14:27

students would not be able to respect them. Anyway,

14:31

many years later I took on the teaching of

14:33

a course that other people generally didn't want to

14:35

teach. And then I was pushed out of that

14:37

so because it became valuable.

14:39

And so I was pushed out and I

14:41

said, that's it. I'm done. I

14:43

can't keep doing this any longer.

14:46

No, done. Well,

14:48

because to your mind and to all the feedback you were

14:50

getting was that the course is going really well. The

14:52

course was going really well and it was

14:55

more than that. I'd taken this course that nobody

14:57

else wanted really because it wasn't good

14:59

for yours. It wasn't something that you benefited

15:01

you in a way that certain classes

15:03

do. If you teach graduate students, that's very good for

15:06

your lab because then they come to your lab, you

15:08

get to find out who's a good student and you

15:10

can recruit them to your lab and so forth. And

15:12

here was a class that wasn't going to be valuable.

15:14

It was a service really. And I was happy to

15:16

do it because I was

15:18

just excited about it. And I had done a previous

15:21

course on which this one was based. And then I

15:23

had to even look at the data. Yeah. I had to

15:25

look at the student evaluations to make sure, yeah,

15:28

yeah, no, I am just

15:30

as good as everybody else and better. And

15:33

yet I'm still being pushed out. I

15:35

said, I just can't do this anymore. I

15:38

just can't. Wow.

15:42

And instead of just not doing

15:44

it anymore though, you decided

15:47

to take action. Well,

15:49

again, I mean, by then I was 50 years

15:52

old. So I had a career. It was my

15:54

life and I was running a lab. I loved

15:56

my work, my scientific research at the time and

15:58

had a wonderful lab. So

16:02

I really wanted to fix the problem and I

16:04

didn't know how to fix it and how do

16:06

you fix a problem like this? And

16:08

I ran through all the standard things people think about.

16:10

You go to the different administrators at different levels

16:12

and you talk to them. And

16:14

they all listened politely and said, well,

16:16

I don't know, that might have happened. Again,

16:19

how could they understand it? Took me 20 years

16:22

to figure out how could they understand from a

16:24

single incident or one or two incidents what you're

16:26

talking about. And then

16:28

I thought of suing, but I knew that

16:30

if you sued an institution, you would fight

16:32

for years and it would destroy you as

16:35

well as maybe bother them, but probably not

16:37

much. And I didn't wanna do that

16:40

and I didn't know what to

16:42

do. And finally, I wrote a letter to

16:44

the president of MIT saying,

16:47

I thought this is my last shot, I'm going to the top. And

16:49

I said, you've got a problem here cuz I've

16:52

discovered this is systemic, invisible, I

16:54

believe, a discrimination that people

16:56

don't intend, but it's very damaging.

16:59

And I decided I had better show

17:01

it to another person

17:05

before I sent it to him. And I

17:07

chose a woman and I had not talked

17:09

to other women really seriously about this for

17:11

the reasons I told. You know, afraid that

17:14

other people will think you're whining. I

17:17

knew they were discriminating against, I didn't think they knew.

17:20

This is so interesting. Anyway,

17:22

I've got my courage and I asked this

17:24

woman, I just respected her so much, Mary

17:26

Lou Padoux. And she was

17:28

such a successful scientist and she was dignified

17:31

and impressive in every way. And

17:33

I asked her to read my letter to the

17:35

president of MIT and see whether she thought it

17:37

was okay, that I should send it to him.

17:40

And she read it and then she

17:43

said she wanted to sign it. She agreed with

17:45

everything I said and that moment literally changed my

17:48

life, changed ultimately MIT.

17:51

And thanks to Kate Cernicky, got

17:54

out and changed the

17:56

world, I guess you'd say in a

17:58

funny way. Hi,

18:01

I'm Katie Haffner, co-executive producer of

18:03

Lost Women of Science. We

18:06

need your help. Tracking down

18:08

all the information that makes our

18:11

stories so rich and engaging and

18:13

original is no easy thing.

18:16

Imagine being confronted with boxes full of

18:18

hundreds of letters in handwriting that's hard

18:20

to read or trying to piece together

18:23

someone's life with just her name to

18:25

go on. Your

18:27

donations make this work possible. Help

18:30

us bring you more stories of remarkable

18:32

women. There's a prominent donate

18:35

button on our website. All you have to

18:37

do is click. Please

18:40

visit lostwomenofscience.org. That's

18:43

lostwomenofscience.org. Nancy,

18:48

I want to get back to that point that you just

18:51

were talking about when Mary Lou offered

18:53

to sign the letter. But

18:55

Kate, what I want to ask you is let's go back to

18:57

1999 for a second. When

19:00

you had that first phone call with

19:02

Nancy and began to learn the story,

19:04

what stood out to you? Oh,

19:07

a couple of things. One, just the sheer fact

19:09

that MIT was going to

19:11

admit that it discriminated against the women on its

19:13

faculty. And that alone, Nancy likes to hear me

19:15

say this, that in my business is what we

19:17

call Man By Its Dog story. It was not

19:19

what anyone was expecting. The second and in some

19:21

ways more interesting thing to

19:24

me was that these women had, you know, the

19:26

reason the president of MIT was going to acknowledge

19:28

this was that the women had gathered all the

19:30

data and written this report to show how they

19:32

were discriminated against and they had numbers.

19:35

And I come from, on my father's side, a

19:37

long background of scientists, and I think I just

19:39

thought like, wow, they did what

19:41

scientists do. They had leaned into their

19:43

science, and I thought that was so clever. Those

19:45

were sort of the two selling points. But then it

19:48

really was that they were

19:50

talking about a different kind of discrimination. And I

19:52

think this even persists today a little bit. We

19:54

think that discrimination, for it really to be discrimination,

19:56

it has to be a door shut in your

19:58

face. You have to basically be told, you

20:00

can't have this because you're a woman, because you're

20:02

a person of color, because you're gay, whatever it

20:05

is. And what they were

20:07

saying was, no, no, no, this is

20:09

what happens after the door is open.

20:11

That's what matters. That's what shapes careers.

20:13

And it's the subtle bias, and it's the

20:15

things, you know, many times, as Nancy said,

20:19

many times it was unintentional. But it really,

20:21

it's insidious and it's stubborn. And in some

20:23

ways, again, I think this

20:25

is still true, it's harder to

20:27

fight than the more egregious examples of certainly

20:30

of gender discrimination, because people aren't sure it's

20:33

real, and the women themselves aren't sure it's

20:35

real. So I think it was

20:37

that these women had done what scientists do, I

20:39

thought they were incredibly ingenious, but also that they

20:41

were illuminating a new kind of discrimination, which I

20:44

was just starting my own reporting career. It

20:46

was not something I thought about, but everything

20:48

they said made sense. And I could say,

20:50

oh, yes, I see exactly how that happens.

20:52

And to get back to the collecting data

20:54

part and speaking science, Nancy,

20:56

do you think that that's one of the

20:59

reasons why this

21:01

story had the success that it did?

21:03

Because you were speaking the same language

21:05

because you were fluent in that language.

21:08

Yes, absolutely. I think that was a

21:11

huge part of it. We

21:13

were so lucky. I mean, MIT is a science and

21:16

engineering school, and we

21:18

were scientists and also later soon

21:20

engineers. So we really were talking the

21:22

same language. I've thought about that. What if it had

21:24

been poets? Would

21:27

it have worked out? I hope so, but I'm not sure. Just

21:30

go back to the thing about Mary Lou. Mary

21:33

Lou was the first woman ever

21:37

in the School of Science at MIT elected to the

21:39

National Academy of Sciences. And

21:42

so that's kind of our stamp of approval. If

21:44

you elected the National Academy of Sciences, you're

21:47

good enough for MIT. So

21:49

maybe Nancy Hopkins wasn't good enough for MIT,

21:51

but Mary Lou Pardoux was. I

21:53

respected her enormously. I knew how good

21:55

she was. And yet I also knew that she

21:57

had been discriminated against. The fact that... she

22:00

knew it. That's the new thing

22:02

I learned. And this woman who had this stamp

22:05

of approval from the world really as

22:07

a scientist had now agreed to it.

22:09

The world just shifted in that moment. It

22:12

really did. She was

22:14

looking at me and I think the same thing was going through

22:16

her head and she was looking at me and I think it

22:18

was this thing of, oh my

22:20

goodness, there's two of us

22:22

who agreed with this. We looked at

22:24

each other and said, you don't suppose there could be more? Because

22:28

you realized the power of

22:31

two. Suppose you had more.

22:33

It really

22:35

was an extraordinary thing. And can you imagine,

22:38

here we are sitting here in this room

22:40

talking to each other about this. But

22:42

to me, it's as if it

22:45

happened yesterday, that moment. It

22:48

changed my life. But that it could have

22:50

this impact after all when it

22:52

became public because it did speak to the truth

22:56

and helped people to understand it. I think that

22:58

was the other thing because I had gone to

23:00

these very good men, wonderful men. So we

23:02

had some wonderful administrators. They listened, but they

23:04

couldn't understand it. And I don't blame them.

23:06

I can see why they had trouble understanding

23:09

it. They just thought it was a difficult

23:11

person you ran into. It was the circumstances

23:13

of that particular experience. There was a reason

23:15

and there always was

23:17

another reason you could ascribe it to.

23:20

So it really required this group coming

23:22

together with the data. And

23:25

I think the data was important, but also it was

23:28

the combination of the data and the

23:30

stories. Because another thing about

23:32

scientists, same is true of journalists, we look for

23:34

patterns. So there's this moment in the

23:36

book where Nancy and Mary Lou decide they're

23:39

going to talk to all these other women at MIT and

23:41

see if they feel the same way. And there's this moment

23:43

after the women come together that they go and they

23:46

speak to the dean of science, who's a man.

23:48

And he says, there are six of these women

23:50

sitting around his conference table and he says to

23:52

me later, he knew them

23:54

all individually and had any one of them come

23:57

to him individually and given the same story.

23:59

story, he would have said, oh,

24:02

well, it's this department head or it's this grant

24:04

that she lost out on, or she's mad about

24:06

this, or she's always been difficult, whatever. But

24:08

seeing and hearing these women one after

24:10

another tell the same version of the

24:12

story, he describes it like the

24:15

greatest scientific epiphany he's ever had. You know, it was

24:17

like, oh, this is, we have a problem

24:19

here. We need to fix this. The other

24:21

thing about it is, you know, the people

24:23

were different departments, different fields, and

24:26

the success of these women, and that was the

24:28

thing about Mary Lou. She was the first one,

24:31

but still, out of that group, they

24:33

knew these people were on track to become

24:36

the next bunch of National Academy members, and

24:38

they did. And so they

24:40

knew how good those women were as a

24:42

group. And when you saw

24:44

it all together, it had

24:46

power. So of the 16 women,

24:49

11 are members of the National

24:51

Academy of Sciences, four have won the National Medal

24:53

of Science. I mean, these were not

24:55

women where you, in any objective way, would look and

24:57

go, eh, they're really not good enough. So

25:00

Nancy, going back to the moment

25:03

when Mary Lou signed your letter

25:06

and you knew you had an ally, what

25:08

did it feel like when you realized you

25:10

had allies? It should be noted some were

25:12

men along the way, but your biggest allies

25:14

were the 15 women. What

25:17

was the impact of that group and how

25:19

did it feel to have those allies? They

25:21

really were and remained for me the

25:23

story. And after Mary Lou and

25:25

I looked at each other and said, you don't suppose there could

25:27

be more? We went and

25:29

said, okay, how many more? So we got out

25:31

of catalog to look at the number of women

25:34

faculty, tenured, we all wanted to deal with tenured

25:36

women, tenured women faculty in

25:38

the six departments of science at MIT. And

25:40

there were only 17 women and 200... And

25:49

so it didn't take very long to find

25:51

these people. And so we

25:53

split it into groups that I'll take half, you take

25:55

half, and I think off we went to meet with

25:58

them. everyone

26:00

we met wanted to join up and

26:03

said, do you have something I could sign?

26:05

So they did become a group. And that

26:07

was the most important thing. After Mary Lou's initial

26:09

reaction for me, that was the next most important

26:11

thing. I became very, very close to these women.

26:14

And I knew where they were all the time. And I would speak

26:16

to this one in the morning and that one at late at

26:18

night. And every day I was talking

26:20

to them. And we never did anything, took a

26:22

step without consulting all of

26:24

them. And everybody's in, everyone

26:27

had to agree. And I would then write

26:29

a memo and I'd send it to the

26:31

dean and say, once we got going, this

26:33

is what we want to do next. And every

26:36

woman had to sign off on it. We needed

26:38

all those people's ideas because they were different

26:40

fields. And it was the common themes that

26:42

told the story. And so finding

26:45

those common themes and making sure everyone was comfortable

26:47

with it and no one was gonna be

26:49

exposed. And we never talked to people about it.

26:51

We were operating in secrecy essentially. So

26:53

people wouldn't be damaged by people knowing we

26:56

were doing this. So to this

26:58

day, I still don't make my decisions

27:00

without calling some of them up and saying, what do you

27:02

think I would do about this? They

27:04

were amazing people. Every one of them

27:06

pioneers, I mean everyone. I

27:09

think Kate, you once said, Nancy couldn't

27:11

have done it without the group and the group wouldn't

27:14

have done it without Nancy. Absolutely. So they were just

27:16

a beautiful marriage there. Yeah, I mean, I often say

27:18

that Nancy is, well Nancy will say it herself. She's

27:20

a reluctant feminist, but I think she was also a

27:23

reluctant leader. But these women

27:25

wouldn't have come forward without Nancy's determination

27:27

to do this. And I think Nancy

27:29

wouldn't have necessarily felt secure

27:31

in that determination without those women behind her. Well,

27:34

and to your point about the

27:36

women going and telling all the stories

27:38

at the same time, it maybe wouldn't,

27:40

it certainly wouldn't have worked without a group.

27:43

And this sort of goes to the title of the

27:45

book. Like everyone thinks they're the exception. Everyone thinks, oh,

27:47

this is just happening to me. Or, oh, that was

27:49

just this one situation. What you have to realize is

27:51

like, no, no, no. This is the rule. This

27:54

is happening to everybody. And the only way we're gonna talk

27:56

about this is to point that out.

27:58

So Kate, it's been over two. decades since

28:00

your first report in 1999. Why

28:04

did you want to return to Nancy's story today?

28:06

Well, again, I thought

28:08

these women were so ingenious in what they'd done.

28:10

They'd really educated me. I think partly

28:12

when I came back to this story to write

28:14

it as a book, I was the age Nancy

28:16

was when she took her magic tape measure and

28:18

measured these, the lab space

28:21

and the office space. And so I

28:23

had seen more and understood, and I

28:25

think I slightly kicked myself for not

28:27

having digested it and learned the lesson

28:29

as a younger reporter. But

28:31

really, I think I just felt like this was

28:33

a real learning opportunity and a way to sort

28:35

of educate people about what we're talking about. How

28:37

does this work? How does bias work? I

28:40

started looking into this as a book idea in January of

28:42

2018. And we were just coming out

28:44

of the surge of the Me Too movement. And

28:47

I was watching the Me Too movement thinking,

28:49

okay, great, I'm glad that we're addressing these

28:51

issues, these very egregious issues. I'm

28:54

sort of amazed it took us this long. But

28:56

what about the problem that I see happening to

28:58

so many more women that I think

29:00

is more stubborn and more

29:03

insidious because you can't identify it. Which

29:05

is this idea of the unconscious bias

29:07

and the small ways in which women

29:09

are marginalized. Not allowed to be on

29:11

the track that men are in terms

29:13

of career promotion, sort of pushed aside

29:15

or ignored. And it's not a big

29:17

aha moment usually. It's really small stuff,

29:19

but that small stuff adds up. And

29:22

to me, I was just looking at the

29:24

world and thinking like, well, that's the problem, why is no

29:26

one talking about that? Let's talk about that. And

29:29

again, I thought Nancy was a generous

29:32

and wonderful vehicle to tell a story through

29:34

because this really was her life. This is

29:36

what happened to her. Absolutely.

29:39

And when you read the report that Nancy

29:41

and the other women had put together, what

29:44

stood out to you? And what

29:46

made you think that this was going to have huge

29:48

ripple effects beyond the scientific community?

29:51

Yeah, I think in the beginning, because my father,

29:53

who was a physicist, had talked to me about

29:55

women and the lack of women in physics, I

29:57

thought, this kind of appeals to

29:59

me, right? I didn't know, and

30:01

nor did Nancy or anybody else at MIT, that this was

30:03

going to rock around the world the way it did. But

30:06

I think it was, what I read

30:08

in the report, I remember a few

30:10

phrases, and it really was this whole

30:12

idea of 21st century discrimination, how discrimination

30:15

works now. It's not the egregious

30:17

stuff. I mean, there is still some egregious stuff, obviously,

30:19

as me too taught us. But it's the subtle

30:21

stuff. And it was this idea, I think you

30:24

had a line in there, Nancy, it was something

30:26

about they'd open the door, but you were tolerated

30:28

but not welcomed, tolerated but not included. And

30:30

that's really the essence of what happens, right? You

30:32

open the door to people, but are you really,

30:36

are you accepting them as full citizens? Nancy,

30:39

switching to some more recent and

30:41

very good news, you

30:43

recently received a prestigious award, the

30:45

National Academy of Sciences Public Welfare

30:47

Medal for your brave leadership over

30:49

the last three decades to help

30:52

make sure more women have fair opportunities in

30:54

science. What did it mean

30:56

to you to receive that award? I

30:58

don't know if I can explain it.

31:02

I was just overwhelmed, honestly. I

31:04

really was and still sort of am.

31:08

And I think there's a couple of reasons, I just

31:10

never thought of it on those terms. I think when

31:12

you set out to cure cancer, you're gonna win the

31:14

Nobel Prize. You have a goal. This

31:17

was something I backed into because you couldn't

31:19

do your work, and

31:21

it wasn't very popular. And

31:23

so to have it, have this outcome, it's

31:25

hard to even grasp. And I

31:27

think the other thing is

31:30

that I realized, after

31:33

I did this and went back and learned

31:35

more about women in science and

31:37

traveled all over the country giving talks on

31:40

this report and met all these women,

31:42

how many women and

31:44

some men gave their lives to

31:47

make it possible for women to have a job. If

31:50

you read the histories from Margaret Ross, such as

31:52

book, for example, Women in Science, oh

31:54

my gosh, what it took for

31:57

women to be allowed to get an advanced

31:59

degree. to become a faculty member of

32:01

these, what do we have

32:03

to have, the Civil Rights Movement, the Women's

32:05

Liberation Movement, Title IX, these

32:09

monumental social movements about how

32:11

social change happens. So

32:13

I feel, yes,

32:15

the MIT story is amazing, and within science,

32:17

I think it really had a certain impact.

32:21

But I felt, gosh, it's

32:24

picked out this particular thing as

32:26

a representative of the work of so

32:28

many people. Actually, Kate

32:30

and I went to Washington, and we went through

32:33

this event, and it was really

32:35

remarkable. And to join the people who

32:37

have been given this award are people

32:39

whose work really did have an impact

32:41

in changing the world. And I think, you

32:43

know, when Kate told the story, it had this

32:46

outcome. I didn't predict it. I wish

32:48

I could claim credit, but I can't. But

32:50

hey, it's what happened. Quite

32:52

a trip. One of the things

32:54

that's been kind of heartbreaking for me is in all

32:56

the time that I was reporting the book, Nancy and

32:58

I would have these conversations, and I felt like

33:01

Nancy, you would constantly be thinking, well, was it

33:04

really worth doing all this work on the women?

33:06

Was that really, that this was sort of somehow

33:08

second best work? And there was a, obviously, as

33:11

there would be, because time is not flexible, there

33:13

was a cost to your science. And I felt like

33:15

you really worried about the cost to your science. And

33:17

so getting this, getting the Public Welfare

33:19

Medal from the National Academy of Sciences, I feel like that

33:21

was the first time that I heard

33:24

you fully acknowledge that, oh

33:26

yes, this work was important. This was a

33:28

big deal. Well, for sure.

33:30

I mean, that's for sure. I think, you know, so you

33:32

realize the thing that you set out to do that was

33:34

so important to you may not be the thing you end

33:36

up doing that other people think is an important thing you

33:38

did. I would say, adding

33:41

to that, that you did all the

33:43

amazing science and this on

33:45

top of it, right? As amazing

33:47

sciences, the men at MIT, and

33:50

also all this other work. But I think, I

33:52

mean, this is something we haven't talked about

33:54

and maybe we don't need to, but you

33:57

do pay a price when you do this. Okay, there is a

33:59

cost. And I think through all the

34:01

time, I think this was the other reason the medal had

34:03

such an amazing effect. Through all those years I was

34:05

doing it, I did it because it had to be done.

34:07

I ended up in a position where I was the person who

34:09

had to be doing it. I felt I'm

34:12

doing something wrong here because so many of

34:14

my colleagues will never understand it and will

34:16

always hold it against you at some level.

34:19

So there's a certain pain associated with it as

34:21

well and that will never go away completely. And

34:23

I understand it. But

34:27

you know, it had to be done. It has to be

34:29

done. Wait, I think that's...say that again. So you were saying

34:31

you feel like your

34:34

colleagues held it against you and so... Of course. ...there

34:37

was pain associated with it, but this kind of took away the pain,

34:39

is that what you mean? It did. It did.

34:42

I think it really did. We've talked very politely about all

34:44

of this due to unconscious bias. The reality

34:46

is underlying that bias is

34:49

a belief that women aren't good enough. That's

34:52

what it comes down to. At the bottom of

34:54

it all, that's what drives that belief.

34:58

So when you stood up against that,

35:00

people don't...of course they don't... Oh,

35:02

thank you for telling me now I got it right. No,

35:04

that's not how it works. No, they still believe it.

35:07

And so you have to deal with that. But

35:10

I think that the National Academy

35:12

did what they did is

35:15

extraordinary and extraordinary on the part of

35:17

the leadership of the Academy and of

35:19

the committee that did this because it says

35:21

it very loud and clear. No,

35:23

this is the way it really is. Nancy

35:27

gave this wonderful talk and there was such a

35:29

prolonged standing ovation afterward for

35:31

her. I mean, I still feel

35:33

it. It was really incredible. You really got the sense

35:36

that Nancy had moved this room and she'd

35:38

moved the world, really. Amazing. What

35:40

a positive note to end on. Well,

35:43

thank you again, Nancy and Kate, for

35:45

sharing this amazing story that continues to

35:48

have such a huge impact. Thank you.

35:51

Terrific. This

35:53

has been Lost Women of Science

35:55

Conversations. This episode was hosted

35:58

by Juliana Lemure, Laura Laura

36:00

Eisensey was our producer, and

36:02

Hans Shee was our sound engineer. Thanks

36:05

to Jeff Del Visio at our Publishing

36:07

Partner Scientific American, and to

36:10

the team at CDM Sound Studios in

36:12

New York. And thank

36:14

you to my co-executive producer Amy Scharf,

36:16

as well as our senior managing producer

36:18

Deborah Unger. The episode

36:21

Art was created by Karen Mevarach,

36:23

and Lizzie Yunnan composes our music.

36:26

Lexia Tia was our fact checker. Lost

36:29

Women of Science is funded in part

36:31

by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and

36:33

the Amwa Jiski Foundation. We're

36:36

distributed by PRX. If

36:38

you've enjoyed this conversation, please go

36:40

to our website, lostwomenofscience.org,

36:44

and subscribe so you will never miss

36:46

an episode. That's

36:49

lostwomenofscience.org. Oh,

36:51

and do not forget to click on

36:53

that all-important donate button. I'm

36:56

Katie Hafner. See you next time. Thanks

37:00

for watching.

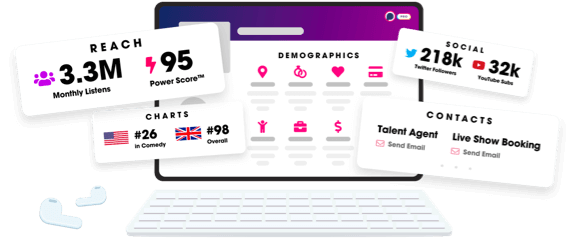

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us