Episode Transcript

Transcripts are displayed as originally observed. Some content, including advertisements may have changed.

Use Ctrl + F to search

0:00

So the King's new lemonade lineup

0:03

is here. Name and a lemonade

0:05

The Smoothie King Way try strawberry.

0:07

Guava Lemonade ask refresher over

0:09

ice a power up in

0:12

it can energize, or a

0:14

blueberry lemonade smoothie lead it

0:16

up being. Made

0:18

with real fruit. Real juice for

0:21

a real sipping good summer. Yeah

0:23

yeah, Data is no Smoothie Kings

0:25

New lemonade lineup of for a

0:27

limited time. Who. Stars Day.

0:59

If you haven't been doing so already,

1:01

you should listen to these episodes sequentially,

1:04

starting with episode 501. Without

1:07

any further ado, enjoy the episode.

1:11

Hello

1:27

and welcome to the History of Japan Podcast,

1:29

episode 537, The New Order. America's

1:35

occupation of Japan came to an end

1:37

earlier than planned, and with little fanfare,

1:39

late in the spring of 1952. The

1:44

impetus, as with so many foreign policy

1:46

decisions made by the United States during

1:49

the 20th century, was the Cold

1:51

War. Seriously, if you're

1:53

trying to explain basically any decision made by

1:55

the US government from about 1945 to 1991,

2:00

the answer is almost certainly because

2:02

of the Kamees. Specifically,

2:05

the outbreak of the Korean War in the summer

2:07

of 1950 drew

2:09

huge numbers of American troops away from

2:11

Japan and towards the peninsula, and

2:14

accelerated an already growing trend towards

2:16

abandoning the lofty early occupation goals

2:19

of a total reconstruction of Japanese society

2:21

in favor of simply getting things up

2:24

and running, so to speak, as a

2:26

Cold War ally of the United States.

2:30

And so on September 8,

2:33

1951, then Prime Minister of Japan

2:35

Yoshida Shigeru found himself in San

2:37

Francisco, signing a final peace treaty

2:39

with the Allies. Well,

2:42

with most of the Allies, given

2:45

the nature of the Cold War, neither

2:47

Soviet representatives nor those of the New

2:49

People's Republic of China were present, and

2:52

given the ongoing Korean War, neither

2:54

Korean government came either. Final

2:58

peace deals with South Korea and China would

3:00

wait until the 60s and 70s respectively, technically

3:04

North Korea and Russia have never signed

3:06

a final peace with Japan. The

3:10

final treaty which Yoshida signed laid out

3:12

the terms of Japan's readmission to the

3:14

family of nations and the regaining of

3:16

its sovereignty, namely the overseas

3:19

assets of the Empire would be confiscated

3:21

and everything other than the four home

3:23

islands and some of the outlying ones

3:25

given up. This

3:27

by the way included Okinawa, which had been

3:30

built up by the United States as a

3:32

base for the potential invasion of the home

3:34

islands late in the Second World War. While

3:37

that invasion never actually materialized,

3:40

Okinawa had become a major hub of

3:42

American power in the Pacific, and so

3:45

part of the deal made at San

3:47

Francisco was that Okinawa would remain under

3:49

American control. The United

3:51

States did not return the territory back to

3:53

Japan until 1971, and

3:56

only then would the understanding that the US

3:58

could continue to use the same. its bases

4:00

there. Beyond

4:03

giving up Okinawa there was one other

4:05

price to pay. After

4:08

Prime Minister Yoshida signed the Peace Treaty

4:10

he was then loaded into a car

4:12

and taken to the other side of

4:15

town to sign a separate document, the

4:17

US-Japan Mutual Security Treaty. This

4:20

treaty had been a precondition for the

4:22

end of the occupation and though it

4:24

was ostensibly an agreement between two equal

4:26

powers, in reality it very much

4:29

was not. Article

4:31

1 stated that quote, Japan grants and the

4:33

United States of America accepts the right upon

4:35

the coming into force of the Treaty of

4:37

Peace and of this treaty to dispose United

4:40

States land, air and sea forces in and

4:42

about Japan. Such forces

4:44

may be utilized to contribute to the maintenance

4:46

of international peace and security in the Far

4:49

East and to the security of

4:51

Japan against armed attack from without, including

4:53

assistance given at the express request of

4:56

the Japanese government to put down large

4:58

scale internal riots and disturbances in Japan

5:01

caused through instigation or intervention by

5:03

an outside power or powers. To

5:07

translate from the original legalese, the US

5:09

had the right to put its forces

5:11

anywhere in Japan to send them anywhere

5:13

it wanted to to contribute to the

5:15

maintenance of peace and security, which is

5:17

very vague language naturally, and did not

5:20

have to check in with the Japanese

5:22

government before doing so. That

5:24

last bit about large scale internal riots

5:27

and disturbances, it's codifying the

5:29

right in case of communist revolution or

5:31

insurrection for the US military to sweep

5:33

in and put the revolt down. Just

5:38

as Galing was the fact that no

5:40

part of this mutual security treaty obligated

5:42

the US to defend Japan in case

5:44

of a war, it merely suggested that

5:46

might happen, and that Article 4

5:49

laid out very vague terms for ending

5:51

the treaty. Quote, this treaty shall

5:53

expire whenever in the opinion of the governments

5:55

of the United States of America and Japan,

5:58

there shall have come into force

6:00

such as United Nations arrangements or

6:02

such alternative individual or collective security

6:05

dispositions as will satisfactorily

6:07

provide for the maintenance by the

6:09

United Nations or otherwise of international

6:11

peace and security in the Japan

6:13

area. Again,

6:16

just to translate, that's a

6:18

very vague precondition that leaves

6:20

a lot up to interpretation

6:22

particularly because both countries have

6:24

to agree that this new

6:26

arrangement will provide for international

6:28

peace and security. In

6:31

other words, Japan could not

6:33

unilaterally decide to end the treaty

6:35

if a future Japanese government ever

6:37

decided it was no longer in

6:39

Japan's interest, it would need American

6:41

permission to do so. Unsurprisingly

6:45

the new security treaty was enormously

6:48

controversial from the jump. Leftists

6:51

in Japan hated it because the document openly

6:53

aligned the country with the US in the

6:55

Cold War and as a result

6:57

made the nation a potential battleground for World

6:59

War III. And

7:02

it's important to remember here that it's something

7:04

of a truism that one of the hardest

7:06

parts of doing history is knowing how the

7:08

story ends. We know the Cold War

7:10

is never going to turn hot, but you have to

7:12

remember in 1952 that's not

7:15

a certainty. The risk of

7:17

Japan getting caught in a nuclear crossfire

7:19

between the United States and the Soviet

7:21

Union felt very real. Even

7:25

those in the political right, which

7:27

Yoshida was, were not huge fans

7:29

given how obviously one-sided the treaty

7:31

was. As early

7:33

as 1955 the Japanese government

7:35

began sending delegations to Washington requesting

7:38

renegotiation of the security treaty though

7:40

those early attempts were all

7:42

rebuffed. More

7:45

ambiguous was the view of the wider Japanese

7:47

public. For example in

7:49

his excellent series Japan a Documentary

7:51

History, David Liu translates an

7:53

opinion survey done by the Major Daily

7:55

Asahi Shimbun on the occasion of the

7:58

coming into effect of the San Francisco.

8:00

go and mutual security treaties. There

8:03

are a whole bunch of questions in this survey,

8:05

all of which are great for getting a sense

8:07

of the public mood. For example,

8:10

the very first one is, do

8:12

you think that as a result of the coming into

8:14

effect of the peace treaty, Japan

8:16

is now independent, or do you think Japan

8:18

is not independent? 41% said

8:21

yes Japan is

8:23

independent, but another 40% said

8:25

some variation of no, either

8:27

only in name or not

8:29

independent, with the final 19% having

8:32

no opinion, which seems pretty high for

8:34

a fairly fundamental question. But

8:37

then again, not having an opinion seemed to be

8:40

the order of the day. For the

8:42

question, during the period when Japan was

8:44

under occupation, was there anything which Shkaap

8:46

or the Japanese government did, which in

8:48

your opinion is good, 47% said yes,

8:52

14% said no,

8:54

39% had, you guessed it,

8:57

no opinion? For

8:59

the same question but replacing do anything good

9:02

with do anything undesirable, the results were 28%

9:04

yes, 26% no, 46% no opinion. And

9:12

by the way, those who said yes were

9:14

asked to elaborate on what was good or

9:17

desirable, their answers emphasized the

9:19

promotion of democracy, followed by land

9:21

reforms that made the countryside more

9:24

equitable, improvement in women's social position,

9:26

expansion of education, and economic assistance

9:28

to Japan. Most

9:31

interesting in my opinion are a series

9:34

of three questions on the American military

9:36

presence in Japan. First,

9:38

respondents were asked why the US military remained

9:40

in Japan, despite the end of the war

9:42

and the end of the occupation. The

9:46

largest segment, of course, said

9:48

no opinion 30%. That was

9:50

followed by to protect Japan 21% to guard

9:52

against communist forces

9:55

18% to maintain Japan's

9:58

internal security 13%. due

10:01

to a lack of Japan's defensive power, 11%, for

10:04

the protection of the United States itself, 4%,

10:07

and to place Japan under surveillance, 3%.

10:12

The next question asked, who requested these American

10:14

troops stay in Japan? 29% said both countries,

10:16

24% just the Americans, 21% the Japanese government,

10:18

26% no opinion. And

10:27

then finally the respondents were asked, do

10:29

you want to see US troops remain

10:32

in Japan? 48%

10:34

yes, 20% no, 16% each

10:37

for, we have no choice so

10:39

either way is fine, and of

10:41

course, no opinion. So

10:45

those are all some interesting numbers, but what do they

10:47

actually tell us? Well, very roughly,

10:50

I think they show us a society

10:52

divided roughly into three chunks. Roughly

10:55

one third was fairly positive about the

10:57

new order, roughly a third opposed for

10:59

one reason or another, and

11:02

roughly third with no time for this

11:04

sort of high level consideration of the

11:06

nature of Japanese sovereignty, because hey, the

11:08

economy is still kinda in shambles, and

11:10

the question of how am I gonna

11:12

feed my family feels a little more

11:14

important than all of this. And

11:18

indeed, that's kinda the essence of Japan in the 50s.

11:21

Everybody's kinda mad about how things are

11:23

going, but they're all mad for different

11:25

reasons. Which leads us

11:27

into talking about the politics of the

11:29

50s, which are really important because they

11:31

are gonna set up the political structure

11:33

of the post-war more generally, up to

11:36

really the present day in a lot of ways.

11:39

We're gonna start off by talking about

11:41

the Japanese left, which in turn was

11:44

subdivided into two distinct movements, the

11:46

communists and the socialists. There

11:49

are, of course, and always have been other

11:51

branches of leftism in Japan, such as anarchism,

11:54

but they never reached the same level of

11:57

support as the more Marxist-aligned left. Now,

12:01

the post-war era started off pretty great for

12:03

the Japanese left, honestly. After

12:05

all, the militarist right-wing government had taken

12:07

Japan to literal ruin, and so by

12:10

comparison the left was looking pretty good.

12:13

Plus, early in the occupation when the

12:15

Americans rolled into town, they let out

12:17

all the jailed socialists and communists from

12:20

prison and loaded their former

12:22

captors into those prisons instead. The

12:24

socialists and communists were even allowed to

12:26

openly organize in ways that had never

12:28

been possible before. In

12:31

fact, in 1947 the socialists actually

12:34

won an election. They

12:36

picked up 150 seats in the diet

12:38

and were able, with the help of

12:40

more centrist parties, to form a governing

12:42

coalition and take the prime minister's seat.

12:45

Given that the Socialist Party had literally been

12:47

illegal just two years earlier, that was quite

12:50

a feat. Unfortunately,

12:52

things did not go great after

12:54

that point. The reverse

12:57

course, which we talked about last week,

12:59

saw a crackdown on the union organizing

13:01

that formed the backbone of socialist support,

13:03

and the party's chosen leader, Kateyama

13:05

Tetsu, was by all accounts

13:07

a lovely and very affable guy who

13:09

did pass some great reforms to labor

13:11

laws and expanded the social safety net,

13:14

but didn't really have any ideas for

13:16

addressing one of the most important issues,

13:19

how to reboot the faltering post-war economy.

13:22

As a result, he was kicked out of office

13:24

about 10 months after taking it. And

13:28

that defeat proved, let's call it,

13:30

fateful. In time-honored

13:33

leftist tradition, in the aftermath

13:35

of Kateyama's fall from grace,

13:37

the Socialist Party started to

13:39

factionalize internally over arguments regarding

13:41

why he had failed. Broadly,

13:45

we can distinguish three big socialist

13:47

factions that emerged as a result.

13:50

First, you have the so-called Left

13:52

Socialists, who tended to be more

13:54

doctrine or Marxists. In other words,

13:56

convinced the capitalistic order of Japan

13:58

had to be dealt with via

14:00

a class revolution of the urban

14:02

proletariat. You

14:04

might be wondering, wait, wouldn't that make them a

14:06

Communist Party, not a Socialist one? Well,

14:09

for one thing, the lines between those are a little more

14:11

complicated than we're going to get into, with

14:13

apologies towards those of you, and I know

14:16

there are very many of these, who are

14:18

very interested in the finer gradations of Marxist

14:20

politics. For another,

14:22

Japan's Communist Party at this

14:24

point was actually more Maoist

14:26

than conventionally Marxist-Leninist, and

14:28

also, more or less imploded in

14:30

the early 50s, when it decided it was

14:33

time to launch a Maoist revolution in Japan.

14:36

The time was not in fact

14:38

ripe for revolution, and the Japanese

14:40

Communist Party's insurrection accomplished little more

14:43

than firebombing some police boxes and

14:45

didn't really gather any public support.

14:48

Only did the revolution fail, but popular support

14:50

for the party as a whole tanked, to

14:52

the point that while it ran for elections

14:54

after trying to overthrow the government, by

14:57

the late 50s the JCP held only a

14:59

single seat in the House of Representatives. On

15:03

the other side we have the Right Socialists,

15:06

closer to what you would call

15:08

Social Democrats, and more in favor

15:10

of gradual shifts in policy via

15:12

Democratic means. And

15:15

then finally we have the Center Socialists, who

15:17

are pretty much what they sound like, they

15:19

fall into the middle of the two extremes.

15:24

Defeat proved very toxic for the dynamic

15:26

between these groups, which ended up ideologically

15:28

at each other's throats over the question

15:30

of how to proceed in the post-war

15:32

era. From the

15:35

perspective of the Left Socialist

15:37

leadership, the Right Socialists were

15:39

basically counter-revolutionaries in sheep's clothing.

15:41

They lacked an ideological commitment to

15:44

change, and their leader,

15:46

Nishio Suihiro, even tacitly endorsed an

15:48

alliance with the United States and

15:50

refused to call himself a Marxist.

15:53

No wonder the workers had abandoned a

15:55

party with such foolish revisionists in it.

16:00

socialist perspective, meanwhile, the left

16:02

socialists were frothing at the

16:04

mouth lunatics, more invested

16:06

in burning the system down than

16:08

actually creating meaningful change in people's

16:11

lives. No wonder voters had lost

16:13

confidence in a party that was

16:16

more concerned with revolutionary grandstanding than

16:18

meaningful policy. These

16:21

divisions were so stark that for

16:23

a good few years the Socialist

16:25

Party actually split up into creatively

16:27

named left and right socialist parties,

16:30

with the two splinter parties being

16:32

more focused on trying to cannibalize

16:34

each other's voters than actually contesting

16:36

the conservatives in elections. In

16:40

1955 the two parties would

16:42

begin the process of putting aside

16:44

their differences to reform a single

16:46

party and challenge the conservatives politically,

16:49

which sounds like a big step, but well,

16:51

let's put a pin in that. So,

16:55

let's talk about conservative politics in

16:57

the 50s, which are in

16:59

a certain sense just as splintered but

17:02

for different reasons. Our

17:04

story starts in 1945 just after

17:06

the end of the war with

17:08

the formation of the so-called Giuto

17:10

or liberal party. This

17:13

was one of the first post-war

17:15

parties to reorganize, primarily put together

17:17

from former members of the pre-war

17:19

Seiyuki. Its mastermind was

17:22

a fellow named Hatoyama Ichiro who we're

17:24

not going to get into in too

17:26

much depth here because we actually did

17:28

a whole series of episodes on his

17:31

family, the Hatoyamas, Japan's biggest political dynasty.

17:34

If you're curious about that, the series starts at episode

17:36

478. For the short version,

17:39

Hatoyama Ichiro was the son of a famous

17:41

politician and had been in the diet for

17:44

decades before the war, and was

17:46

thus a natural fit to take leadership

17:48

of the post-war conservative movement. democratic

18:00

elections opposed to, from their

18:02

perspective, the excesses of left-wing

18:05

political movements. Hatoyama

18:07

was banking on the idea that this was

18:09

pretty much American politics in the nutshell, and

18:12

that given America's victory over Japan, people

18:15

would be drawn to an ideology that

18:17

was associated with the winning side. And

18:20

he was absolutely right, the jiyuto

18:22

cleaned up in Japan's first post-war

18:24

election in Unfortunately

18:29

for him, Hatoyama wouldn't benefit much

18:31

from this because right after the election,

18:34

as he was on the cusp of

18:36

becoming Prime Minister, something not even his

18:38

famous father had managed, he was notified

18:41

that SCAP had purged him because

18:43

of his participation in wartime cabinets as

18:45

a minister. Thus he

18:48

was no longer eligible for any office,

18:50

including the Prime Ministership. And

18:52

so Hatoyama had to go into a sort

18:54

of forced retirement. And

18:58

the role of Prime Minister for the victorious

19:00

Liberal Party fell to its

19:02

second man, an old friend

19:05

of Hatoyama's, Yoshida Shigeru, a figure

19:07

who looms very large indeed in the

19:09

history of post-war Japan. Yoshida,

19:13

unlike Hatoyama, was not a politician

19:15

by trade. He'd been a

19:17

part of the foreign ministry, a diplomat

19:19

who'd been pushed out of leadership during

19:21

the war years because of a politically

19:24

unpopular Anglophile streak. Because

19:27

he'd been given the boot like this,

19:29

unlike Hatoyama he couldn't be accused of

19:31

having collaborated with the wartime government. Yoshida

19:34

would take the Liberals in a different direction

19:36

from Hatoyama. As a

19:39

bureaucrat by training he was inherently

19:41

mistrustful of politicians and tended

19:43

to recruit his closest confidants from the

19:45

bureaucracy. For example, his

19:47

two political proteges, Ikeda Hayato

19:50

and Satoei Saku, were both

19:52

ex-bureaucrats, actively from

19:54

the finance and railway ministries. Hatoyama

19:59

had also been an opponent. of Article

20:01

9, the clause inserted by the Americans

20:03

into the Constitution banning Japan from having

20:05

a military. He felt, not

20:07

without some reason, that it was an

20:10

unfair restriction on Japan becoming a normal

20:12

nation once again, particularly given

20:14

that Germany had not been similarly

20:16

treated during its occupation. Yoshida,

20:20

by contrast, did not care about

20:22

normality, he cared about pragmatics. Militaries

20:25

were an expense that, barring a war

20:28

Japan was unlikely to fight anytime soon,

20:30

didn't offer much in return. He

20:33

was more than happy to have an official reason not

20:35

to spend money on an army, particularly

20:37

once the Cold War got going and

20:39

the Americans came to town saying, hey

20:41

actually since you're our allies, could you

20:43

build up some armed forces to help

20:45

defend Asia? Yoshida

20:48

could point to Article 9 and say hey you

20:50

know I'd love to help you, but we have

20:52

this great constitution that you gave us and we

20:54

are so grateful for it and it says we

20:56

can't. He

20:58

did sign off on some limited rearmament

21:00

in the form of the modern day

21:02

Japan self-defense forces, legally justified,

21:05

so the government argued, because

21:07

Article 9 banned war potential,

21:09

which was a distinct category

21:11

from self-defense potential, which

21:14

is splitting hairs on basically the

21:16

subatomic level, but it worked

21:18

and to this day Article 9 remains

21:20

a part of the constitution and

21:23

the Jie Tai, the self-defense

21:25

forces, continue to operate with

21:27

some restrictions in place to

21:29

ensure their self-defense potential never

21:31

becomes war potential. Hatoyama

21:35

would eventually be removed from the purge rules

21:37

at the end of the occupation, at which

21:39

point he went to his old friend the

21:41

Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru and said, hey thanks

21:43

for holding down the ship, but I'm back

21:45

now and I can take the liberal party

21:47

over again. Yoshida

21:50

though was unwilling to give up the party

21:52

he'd spent such a long time building up.

21:55

Sure, Hatoyama had founded the party, but

21:57

Yoshida had run it far longer than

21:59

Hatoyama had even been involved by this

22:01

point, and so he said, no

22:03

thank you. From

22:06

here, things unfolded in a way likely

22:08

to be familiar to anyone who has

22:10

ever experienced the world of petty personal

22:12

drama. Hato-yama, furious,

22:14

left to found his own

22:16

party, the Minxuto, or Democratic

22:18

Party, which despite being also

22:21

a conservative party, then went

22:23

to war against the liberals.

22:26

Seriously, Hato-yama ended up siding with the

22:28

Socialists, who hold a no-confidence vote and

22:31

boot Yoshida from office in 1954. Not

22:35

that the liberals responded any better, Hato-yama

22:37

had suffered a stroke a few years

22:40

back and once he became Prime Minister,

22:42

the liberals set about constantly calling him

22:44

in for 10-hour sessions of questioning, one

22:47

of the rights of any parliament, in

22:49

hopes of re-aggravating his condition. You

22:53

can see why, given all of this very

22:55

petty drama, the left and right Socialists felt

22:57

they had a chance to take these people

23:00

down if they combined forces. Unfortunately

23:03

for the Socialists, it didn't quite work out

23:06

that way because, once news got round that

23:08

the Socialists were planning to heal their old

23:10

wounds and come back together, momentum

23:12

began building among the conservative parties to

23:14

do the same thing. After

23:18

all, while Yoshida and Hato-yama each hated

23:20

each other by this point, they were

23:22

also both old men, respectively 77 and

23:25

72 at this point, and

23:27

their younger protégés were less concerned

23:30

with their infighting. The

23:33

result was that, just a few

23:35

months before the merger of the

23:38

Socialist parties, the liberals and democrats

23:40

agreed to come together as well

23:42

into a new party creatively named

23:44

the Liberal Democratic Party, or Jimintol,

23:47

for short. The

23:49

LVP, as it's known in English, has been

23:52

the most dominant force in Japanese politics since

23:54

it was founded in 1955. From

23:58

that year, it has lost control of

24:00

the national government for only six years

24:03

in total, and that looks

24:05

unlikely to change anytime soon. We'll

24:08

get into the reasons why it has managed

24:11

this in a future episode, for now I

24:13

want to focus on how politics for the

24:15

next few years unfolded. At

24:19

the time of the LDP merger,

24:21

Hataoyama's Democrats were stronger than Yoshida's

24:24

liberals. Yoshida had

24:26

governed the country during the vast majority

24:28

of the occupation and immediately afterwards, but

24:31

continuing economic problems meant many of

24:33

his former voters were open to

24:35

an alternative as long as

24:37

that alternative wasn't the Socialist Party. Thus,

24:41

the new LDP was very roughly

24:43

one part Yoshida liberals to two

24:45

parts Hataoyama Democrats, and

24:47

though Hataoyama himself would retire in 1956, one

24:51

of his proteges would dominate the party for the

24:53

next few years. That

24:56

protege was Kishi Nobusuke, formerly a

24:59

bureaucrat in the Japanese puppet regime

25:01

of Manchukuo who'd actually been imprisoned

25:03

by the Americans during the occupation

25:06

in preparation for a war crimes

25:08

trial before those trials had been

25:10

quietly abandoned during the reverse course.

25:15

After dodging that particular bullet, Kishi went

25:17

into politics and depending on who you asked

25:19

either worked his way up to be

25:21

Hataoyama's right hand man by virtue of his

25:24

dedication and talent, or cynically

25:26

manipulated a doddering old man into giving

25:28

him power. Confusingly

25:31

enough, by the way, Kishi was

25:33

also the biological brother of Yoshida

25:36

Shigeru's protege Sato Eisaku. Kishi

25:38

was the second of three boys and had

25:40

been adopted by his childless uncle. Kishi's

25:45

tenure as leader of the liberal Democrats is important

25:47

for setting the tone of the new party in

25:49

a few different ways. For

25:51

one thing, Kishi knew how to win

25:53

elections effectively. During his time

25:56

as Prime Minister, he was able to hang on

25:58

to a majority during a general election in Japan.

26:00

in 1958 and decisively win

26:02

a House of Counselors election in 1959, largely by

26:04

virtue of good political

26:07

messaging. He announced

26:10

that revision of the Security Treaty,

26:12

a popular cause across the political

26:14

spectrum, would be the hallmark of his

26:16

tenure in office. He

26:18

was also very clever about playing on the

26:21

economic anxieties of voters. In the

26:23

1959 House of Counselors election

26:25

he was able to win the

26:27

LDP 10 more seats by focusing

26:29

on a recently released economic plan

26:31

penned by Ikeda Hayato, the

26:33

heir of Yoshida Shigeru as the head of the old

26:35

liberals, to double the average income

26:38

in Japan over the next 10 years. He

26:42

also wasn't above fighting dirty. Kishi

26:46

went after the socialists as

26:48

closet revolutionaries who wanted to

26:50

throw Japan into chaos. He

26:53

used the power of the government to go after

26:55

their bases of support. For

26:57

example, one of the most militant

26:59

sources of anti-LDP opposition and support

27:01

for the Socialist Party was Nikkyo-so,

27:03

the Japan Teachers Union, which

27:06

Kishi was able to effectively break

27:08

in 1958 through the installation

27:10

over fierce socialist opposition of

27:13

an efficiency rating system that

27:15

graded teachers on performance. In

27:19

practice, like all attempts to measure

27:22

intangible things like good teaching through

27:24

metrics, the numbers were very easy

27:26

to manipulate, and thus Kishi's

27:29

supporters in the education ministry could put together

27:31

a case to fire the most militant members

27:33

of the union, basically at will. I

27:37

don't want to make it seem like Kishi was a

27:39

political genius though, he had a few bad

27:41

missteps too. For

27:43

example, Kishi was very vocal in

27:46

his desire inherited from Hatoyama to

27:48

get rid of Article 9 and

27:50

fully normalize the military, which

27:52

did win him some support from

27:54

conservative quarters, but also galvanized his

27:56

opposition. After all,

27:58

if you had even the slightest qualms about

28:00

bringing the old military back, well you'd better

28:02

vote for the socialists, because

28:04

in particular if Kishi ever won a

28:07

two-thirds majority in both houses of the

28:09

Diet, he would have the numbers

28:11

to revise the Constitution, get rid of Article

28:13

IX, and implement the policies he

28:15

wanted. So you

28:17

might not be a socialist, but you'd better still vote

28:19

for them if you wanted to stop him from doing

28:21

that. Similarly,

28:24

a revision in 1958 to the

28:26

police duties law, portrayed by Kishi

28:29

as necessary to fight subversion by

28:31

expanding rules around warrantless search, made

28:34

him look like a wannabe dictator to many

28:36

moderates who previously had been on the fence

28:38

about him, and led some factions

28:40

of his own party to be increasingly

28:42

wary of their ostensible leader. And

28:46

to be fair, Kishi did not do much himself

28:48

to help this impression at all. He

28:51

was a bureaucrat to the core,

28:53

and had the classic Japanese bureaucrats

28:55

disdain for the opinion of anyone

28:57

deemed less elite than himself, which

29:00

is to say basically everyone. Kishi

29:03

was infamous for being snobbish, unwilling to

29:06

listen to criticism, and generally just being

29:08

frankly kind of an ass on a

29:10

personal level. All

29:13

of these factors came to a

29:15

head in 1960 around one of

29:17

Kishi's prize goals, and fundamentally shaped

29:19

post-war society in the offing. The

29:23

impetus was, of course, the

29:25

US-Japan Mutual Security Treaty, which

29:27

after three years of pushing,

29:29

Kishi was finally able to

29:31

renegotiate with then American President

29:33

Dwight Eisenhower. The

29:36

new treaty text was far more favorable

29:39

to Japan. It actually did include

29:41

a commitment on the part of the United States

29:43

to defend Japan in case of attack, and

29:46

some requirements around consultation before

29:48

America deployed forces overseas. This

29:51

time it even included a system for adjusting

29:53

the- And

29:55

this time there was even a system in place

29:57

for adjusting the terms of the treaty or getting

29:59

of it in the future, all

30:01

of which gave Japan a lot more agency

30:04

in the future of the security treaty and

30:06

its relationship with the US than had existed

30:08

previously. Kishi

30:11

had every expectation that his revisions

30:13

would be popular. After

30:15

all, across the political spectrum the security

30:17

treaty had a lot of critics. What

30:20

he didn't realize though was that those critics

30:22

were coming from very different places. Generally

30:27

speaking, right-wing nationalists as well

30:29

as most liberals supported the

30:31

treaty. After all,

30:33

it created a way more equitable

30:36

US-Japan relationship while still ensuring the

30:38

country was protected by the world's

30:40

greatest superpower against the threat

30:42

of the Soviet Union. But

30:44

there were plenty of others who were less than happy

30:46

about the changes. For example,

30:48

a surprising number of business leaders were

30:51

concerned the treaty would distract from a

30:53

more neutralist policy that would keep Japan

30:55

out of the Cold War altogether, and

30:58

more importantly, might potentially allow

31:00

the country to trade with both the

31:02

United States and the Soviet Union, and

31:04

maybe even China, vast and close by

31:07

markets with a lot of potential to

31:09

help rebuild Japan economically. Much

31:12

more vocal, of course, were left-wing opponents

31:14

of the treaty who remained worried that

31:16

it tied Japan too closely to the

31:18

US, and thus painted a giant target

31:20

on the nation's back in case of

31:22

hostilities with the Soviet Union. At

31:26

first it was mostly this left-wing opposition

31:28

that made noise about the treaty. The

31:31

revisions were announced in the late 1959

31:33

and immediately left-wing groups began to organize

31:35

to protest it, while the socialists announced

31:37

plans to tie the treaty up in

31:39

debate in the diet. Kishi,

31:42

after all, could sign the treaty, but

31:44

it wouldn't go into effect until the

31:47

diet ratified it. Still

31:50

that opposition wouldn't be enough to stop

31:52

the treaty's momentum, eventually. The

31:55

LDP had a majority in both houses of

31:57

the diet, even if it didn't have a

31:59

two-thirds one. and a small number of protesters

32:01

could draw headlines, but not a lot else.

32:05

But then Kishi made a huge

32:07

mistake. You see,

32:09

the socialists proved more effective than he

32:12

anticipated at galvanizing protest and wasting time

32:14

in the diet, bolstered

32:16

first by the overthrow of two

32:18

US-aligned dictatorships in the spring of

32:20

1960 in Turkey and

32:22

more importantly neighboring South Korea. This

32:25

seemed to suggest to the socialists

32:27

that unpopular US client regimes, which

32:29

in their eyes was what Kishi

32:31

represented, could be felt by massed

32:33

protest. Then

32:37

and far more importantly on May

32:39

1st 1960 an American U-2 spy

32:41

plane, piloted by Francis Gary Powers,

32:44

was shot down over the Soviet

32:46

Union leading to a huge flare-up

32:48

in Cold War tensions and growing

32:50

concern in Japan when it came

32:52

out that several American U-2s were

32:55

based there, though not Colonel Powers'

32:57

plane which was based in Pakistan.

33:01

Even Kishi's own allies, or to his

33:03

mind subordinates in the LDP, were suddenly

33:05

a bit less sanguine about calling a

33:07

vote to ratify the new treaty, as

33:09

concerns about being tied to the US

33:11

in the Cold War suddenly seemed a

33:13

lot less abstract than they had a

33:15

few months earlier. Kishi

33:18

was now staring down the barrel of a huge

33:20

political mess. The diet was

33:23

scheduled to go on its summer recess

33:25

on May 26th and President Eisenhower had

33:27

planned to come to Japan in June

33:29

to celebrate 100 years

33:31

of US-Japan friendship, 1860 being

33:34

the year the Tokugawa Shogunate had sent

33:36

an embassy to the US to ratify

33:39

the Harris Treaty. Kishi

33:42

had this whole elaborate plan to present

33:44

Eisenhower with a ratified treaty, make a

33:46

big celebration of the whole thing, spike

33:48

the political football the whole nine yards.

33:51

Now it was coming apart in his face. But

33:55

Kishi also had a plan. As

33:57

far back as April 14th he'd

33:59

put together a in Anpo Shonin

34:02

Tokubets Taisaku-Iinkai or Committee on Special

34:04

Measures to ratify the Security Treaty,

34:07

though its members somewhat grimly nicknamed

34:09

it the Anpo Tokkotei or

34:11

Anpo Kamikaze Squad. It

34:15

was tasked with finding a way to

34:17

get the treaty ratified by any means

34:20

necessary and oh boy did they fulfill

34:22

their mandate. On

34:25

May 19th, as it was clear that

34:27

ordinary measures were failing to get the

34:29

treaty through and exactly one month before

34:32

Eisenhower was slated to arrive, Kishi

34:34

struck. The Speaker

34:36

of the House, an LDP member and

34:38

Kishi ally named Kyo Seiichiro set up

34:40

a motion to extend the diet session

34:42

by 50 days, planning to

34:44

then immediately call a vote to

34:47

ratify the treaty without any further

34:49

debate or discussion. This

34:52

was a very canny strategy. Japan

34:56

still has a bicameral legislature with

34:58

the current upper house of councillors

35:01

replacing the old upper house of

35:03

peers. However, the lower

35:05

house, the House of Representatives, has a lot

35:07

more power, similar to the UK system where

35:09

the Commons is much more powerful than the

35:11

House of Lords. In

35:14

this specific case, what matters is that

35:16

the Constitution says that if the House

35:18

of Representatives approves a law or treaty

35:21

and the councillors never vote on it,

35:23

after 30 days that bill or

35:25

treaty is automatically approved anyway, provided

35:28

that the diet is still in

35:30

session over those days. So

35:33

all Kishi had to do was get this

35:35

quick little ambush vote finished, get

35:37

the treaty vote done before the socialists

35:39

could stop him, and after 30 days

35:41

it would be the law automatically. On

35:46

paper it's pretty ingenious, if

35:48

somewhat morally questionable, but

35:50

things didn't work out quite as smoothly as all

35:52

that. The socialists had been

35:55

working on their own emergency plans, hiring

35:57

up the brawniest young men they could

35:59

find as as secretaries to get

36:01

those men freely into the diet

36:03

building. When word came down

36:06

of what Kishi was doing, it

36:08

became time to make use of those

36:10

new secretaries the Socialists announced a sit-in,

36:12

physically blockading the diet with all of

36:14

their assistance, to prevent a vote on

36:17

an extended session from taking place. Speaker

36:20

Kyosei was physically barricaded into his office,

36:23

while the Socialists put the word out

36:25

of what was happening, and outside the

36:27

protests started to swell. Many

36:30

of these new protesters were animated

36:33

less by concern over the treaty,

36:35

and more by the behavior of

36:37

their Prime Minister, who was perceived,

36:39

not unjustifiably, as acting in a

36:41

very undemocratic way. Around

36:45

11pm on May 19th, Speaker Kyosei

36:47

took the extreme step of summoning

36:49

the police to physically remove

36:51

the Socialist blockaders from the diet

36:53

building, only the second time

36:56

the police had ever entered the diet

36:58

building, and the only time in Japanese

37:00

history members of the diet have been

37:02

detained while inside of it, including during

37:04

the pre-war and World War II periods.

37:07

If you're wondering what the other time was by the

37:10

way, that was four years earlier in 1956, during

37:13

some particularly intense debates over

37:15

doing away with occupation era

37:17

school board reforms and re-centralizing

37:19

the education system. The

37:23

Socialists were physically dragged out of the

37:25

building by the police, and just before

37:27

midnight Kyosei was physically hauled up to

37:29

the Speaker's rostrum by his LDP allies.

37:33

Votes were called in quick succession to extend the

37:35

session and approve the treaty, all

37:37

of this broadcast live by

37:39

NHK. Both

37:41

votes passed overwhelmingly given that there was

37:43

no longer an opposition left in the

37:45

building. Kyosei's

37:47

maneuver got the treaty through, 30 days

37:50

would pass and the security treaty became law,

37:53

but it came at great cost,

37:55

even those who had no particular

37:57

interest in the treaty issue now

37:59

saw Kyosei as a threat to

38:01

the people. the stability of Japanese

38:03

democracy. The protests outside the diet

38:05

exploded, tens of thousands of people

38:07

took to the street for daily

38:09

rallies against Kishi, and by this

38:12

point it really was less of

38:14

an anti-treaty protest and more of

38:16

an anti-Kishi protest. Even

38:18

conservative newspapers like the Mainichi Shimbun began

38:21

calling for the Prime Minister to resign,

38:24

as did business leaders who donated to

38:26

the LDP but were worried about political

38:28

instability. In

38:30

the end, by mid-June a series of

38:32

violent incidents destroyed what little support Kishi

38:35

had left. First

38:37

on June 10th, James Haggerty,

38:39

President Eisenhower's press secretary, arrived

38:42

at Haneda Airport in Tokyo to set up

38:44

for the President's arrival in 10 days time.

38:47

His car out of Haneda was quickly mobbed

38:49

by 6,000 protesters.

38:52

They smashed the car up so badly the

38:54

roof caved in. Riot police

38:56

who tried to get to Haggerty were forced

38:58

back with a volley of thrown rocks, and

39:00

in the end a US Marine helicopter had

39:03

to be sent in to get Haggerty out.

39:07

Five days later, protesters attempted to

39:09

storm the Diet building itself, getting

39:11

into a day-long street battle with

39:13

the police as well as right-wing

39:15

agitators who had arrived to counter-protest.

39:20

In the ensuing violence, one of the

39:22

protesters, a young girl named Kanba Michiko,

39:24

was killed. None

39:27

of this stopped the ratification of the treaty,

39:29

which officially came into force at midnight on

39:31

June 19th, though the instruments

39:33

of ratification had to be snuck

39:35

into Kishi's house in a candy

39:37

box for his signature to escape

39:39

the protesters outside. However,

39:44

Kishi's popularity was in the pits. He

39:46

resigned one month later. In

39:50

my view, these protests are one of the most important

39:52

moments in post-war history, first because it secured a cornerstone

39:54

of Japanese foreign policy going forward. From these in on

40:00

In the most auspicious beginnings, the US-Japan

40:02

Mutual Security Treaty would remain in force

40:04

down to this very day, and the

40:06

US-Japan alliance, though it was born

40:08

in somewhat controversial circumstances as we've

40:11

seen, remains a cornerstone of

40:13

Japan's foreign policy. Second,

40:16

Kishi's fall from grace would open up

40:18

the doors to a radical remaking of

40:20

the liberal democratic party at the hands

40:22

of the guy who took over for

40:24

him, and would transform both the party

40:26

and Japan itself in the process. But

40:29

that's for next week, thank you very much

40:31

for listening. This

40:34

show is a part of the Facing Backward

40:36

Podcast Network, you can find out more about

40:38

this show and our other shows at facingbackward.com,

40:41

and you can support the

40:43

network at patreon.com/facingbackward. Special

40:45

thanks to those who have given at our shout out tier,

40:48

Yann Leonard, Steven Elkins, Martin

40:50

Oliveira, Clark Canning, Ian Kellat,

40:53

Matt Haines, Jackie Froestacher, Monkey

40:55

Sack, Leila McCulloch, Karen Murphy,

40:58

Peter Wales, Robert Prine, William

41:00

Arno, Jonas Brandis, Nicholas Kroll,

41:02

Jerry Spinrad, Jared Stevens, Jeffrey

41:05

Dwork, Stefan Hruschka, Joshua

41:07

Kane, Robbie N. Cat, Jacob Key,

41:09

Aaron Finkbeiner, and anonymous

41:12

Anna's Hummingbird, Mark Tsai, Gil,

41:14

Leslie Ikuta, Trash Taste Enjoyer,

41:16

John, Christopher, Harrison Reis, Inoue

41:19

Enrios Ghostbusters,

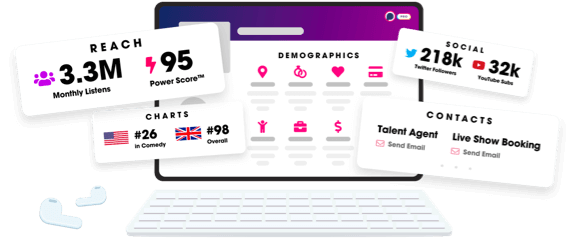

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us