Episode Transcript

Transcripts are displayed as originally observed. Some content, including advertisements may have changed.

Use Ctrl + F to search

0:00

Thanks for listening to Gone Medieval. You

0:03

can get all History Hits

0:05

podcasts ad-free, early access and

0:07

bonus episodes along with hundreds

0:09

of original history documentaries by

0:12

subscribing. Head over to

0:14

historyhit.com forward slash

0:17

subscribe. The

0:19

new Boost Mobile network is offering unlimited talk,

0:21

text and data for just $25 a month

0:23

for life. That sounds

0:25

like a threat. Then how do you think we

0:27

should say it? Unlimited talk, text and data for

0:29

just $25 a month for the rest

0:31

of your life? I don't know.

0:34

Until your ultimate demise. What

0:36

if we just say forever? Okay. $25 a

0:38

month forever. Get unlimited talk, text and

0:40

data for just $25 a month with

0:42

Boost Mobile forever. After 30 gigabytes, customers may

0:44

experience slower speeds. Customers will pay $25 a

0:47

month as long as they remain active on the Boost Unlimited plan.

0:50

Ryan Reynolds here from Mint Mobile. With the

0:52

price of just about everything going up during

0:54

inflation, we thought we'd bring our prices down.

0:57

So to help us, we brought in a reverse auctioneer, which is apparently a thing. Mint

0:59

Mobile Unlimited Premium Wireless! Have it to get 30, 30, a bit to get 30, a

1:01

bit to get 20, 20, a bit to get 20, 20, a bit to get 20,

1:03

a bit to get 20, a bit to get 20, a bit to get 20, 20,

1:05

a bit to get 20, a bit to get 20, 20, a bit to get 20,

1:07

a bit to get 20, 20, a bit to get 20, a bit to get 20,

1:09

a bit to get 20, a bit to get 20, a bit to get 20, 15,

1:11

15, 15, just 15 bucks a month. Sold! Give it a try at mintmobile.com/switch. $45

1:14

upfront for three months plus taxes and fees. Prom or eat

1:16

for new customers for limited time. Unlimited more than 40 gigabytes

1:18

per month. Slows. Full turns at mintmobile.com. Hello,

1:26

I'm Matt Lewis. Welcome to Gone

1:28

Medieval from History Hit, the podcast

1:30

that delves into the greatest millennium

1:32

in human history. We've got the

1:35

most intriguing mysteries, the gobsmacking details

1:37

and latest groundbreaking research from the

1:39

Vikings to the printing press, from

1:41

Kings to Popes to the Crusades.

1:44

We cross centuries and continents to

1:46

delve into rebellions, plots and murders

1:48

to find the stories big and

1:50

small that tell us how we

1:53

got here. Find out

1:55

who we really were with Gone

1:57

Medieval. History

2:02

in flames. It's an evocative

2:05

title for a book. Bonfires

2:07

of paperwork have accompanied human

2:09

upheaval for centuries, eradicating,

2:12

making space for rewriting

2:14

or to encourage forgetting. Some

2:17

was wanton, some a careless

2:19

side effect of conflict. Imagine

2:22

standing in the centre of Paris

2:24

as revolutionaries sweep away the old

2:26

ways, along with the ashes of

2:28

centuries of records and memories. Would

2:31

you have placed a hand into the fire to save

2:34

something for us to read more than

2:36

two centuries later? How

2:38

would you pick which singed collection to

2:40

save? How much of what

2:42

we might have known about the past has

2:44

been consumed by the fires of revolution

2:47

and war? How much has

2:49

been lost? And what is it

2:51

that was destroyed? These are

2:53

some of the questions tackled by

2:56

my guest's new book, History in

2:58

Flames, the destruction and survival of

3:00

medieval manuscripts. And

3:02

that guest is a favourite historian of

3:04

mine. Having embarrassed him at Chalk Valley by gushing

3:07

relentlessly when I got to interview him on stage,

3:09

I'll try and play it cool now. Robert

3:12

Bartlett is Professor Emeritus at the

3:14

University of St Andrews whose books

3:16

and television series have brought medieval

3:18

history to hungry new audiences. If

3:20

you haven't seen them yet, find them out.

3:23

But wait until after you've listened to this

3:25

episode. Welcome to Gone Medieval, Robert. Thank you.

3:27

History in Flames, I guess my first question

3:29

would be, why did you want to write

3:31

this book about the things that we've lost?

3:34

Well, if you're a medieval historian, you

3:36

spend years or in my case

3:38

decades working with the

3:40

evidence which is manuscript material.

3:43

Everything you get from the Middle Ages, written

3:46

evidence is written by hand. That gives it

3:48

a particular feel. I always remember the first

3:50

time I sat down with a genuine medieval

3:52

manuscript when I was in my early 20s.

3:55

The smell is very distinctive, but because

3:57

the material is all much

4:00

less of it than in modern

4:02

times when you have a print culture, and

4:04

it's vulnerable. It can be

4:06

destroyed in all sorts of ways, flood and

4:09

fire and so on. So you

4:11

think about how precarious this is. And

4:14

so I looked at

4:16

some cases when a very

4:19

large amount of that

4:21

medieval manuscript material was destroyed in

4:24

one catastrophic event. I've got five

4:26

case studies. So it's

4:29

to discuss what there was,

4:32

what we've lost, how do we know

4:34

what we've lost, because it's no longer

4:36

there, and what can be done to

4:38

fill that gap, if anything. So those

4:40

are all questions that came straight out

4:42

of working on a manuscript culture. Yeah,

4:44

I guess we fall into that Donald

4:46

Rumsfeld thing of there's known knowns and

4:48

there's known unknowns and there's unknown unknowns.

4:50

Absolutely, absolutely. A very simple example that

4:52

I gave is the plays of Aeschylus,

4:54

a very famous Athenian dramatist. And

4:56

I think there's something like either five or

4:58

six that actually survive to this day. That

5:00

represents about less

5:03

than 10% of the

5:05

plays that we know he wrote. And

5:07

we know he wrote them from references in

5:09

other authors, occasionally quotations from

5:12

him in other authors. And

5:14

just now and again, since they've had the

5:16

exploration of the papyri in the Egyptian desert,

5:18

sometimes you turn up a little scrap that

5:20

has a little bit of Aeschylus on it,

5:22

but it's not in any surviving play. If

5:25

anyone was going to sit down and write

5:27

about Aeschylus, they'd have to be really aware

5:29

that you've only got 10% of

5:31

his plays. So when we think about what's

5:34

come down to us from particularly the medieval

5:36

period, you discuss in the book

5:38

a little bit about how the materials that

5:40

are used can influence the chances of survival.

5:42

So things are written maybe on clay tablets,

5:44

then papyrus scrolls, then parchment books. Can

5:47

you talk us through a little bit

5:49

of the advantages and disadvantages of each

5:52

of those mediums? Yes, the origins of

5:54

the Western tradition of writing are in

5:56

Mesopotamia. And there the first writing is

5:58

on clay tablets. And it's

6:00

a kind of writing called cuneiform in

6:02

which a read was used to imprint

6:04

the marks on a wet clay tablet,

6:06

which was then baked or sun dried.

6:09

And the advantage of that from the point of view

6:11

of survival is that it's very

6:14

much less vulnerable to

6:16

fire than other forms of

6:18

written material because it's already baked. One of

6:20

the problems about getting access to all that

6:22

material is that there's very few people who

6:24

can read that stuff. And of course, there's

6:26

thousands of these things that have been found

6:29

over the years of excavation, but

6:31

the amount of it that has been interpreted

6:33

and even more translated means that it's a

6:35

world where there's plenty to find out, but

6:37

it'll take a long time. And

6:39

then you move through time to papyrus,

6:41

which is made from reeds from the

6:43

Nile. So it's a quite different

6:45

kind of material altogether, much more vulnerable in the

6:48

sense that it can be ripped and it can

6:50

be burned quite easily. That's

6:52

the kind of material you have, which

6:54

was kind of standard in the classical

6:56

world, the world of ancient Greece and

6:58

Rome. All the great works

7:00

that one thinks of, Homer and Virgil

7:02

and so on, would all be in

7:04

the form of papyrus scrolls and

7:06

the scroll would be a roll. And

7:09

very often these works, you find them in modern

7:11

editions, there'll be book one, book two, et cetera.

7:13

The book that we have nowadays in a printed

7:15

edition corresponds to a scroll. So how

7:17

many scrolls there were for these things. And excitingly,

7:19

it's taken us a bit away from the middle

7:22

ages. When Herculaneum, the

7:24

twin sister of Pompeii, was

7:27

excavated, one of the

7:29

villas they found there was completely full

7:31

of hundreds and hundreds

7:33

of these papyrus rolls. And

7:36

the problem was they'd been charred by

7:38

the heat and the fire of Vesuvius.

7:40

So no one wanted to unroll them. If

7:43

you unrolled them, they probably crumble. But

7:45

just recently, very sophisticated technology has

7:47

been used to try to read

7:50

what's in those scrolls without actually

7:52

unrolling them. This is a very

7:55

complicated task. I don't claim to

7:57

understand the technology myself. first

8:00

time, people can actually begin to say,

8:02

well, that's what this scroll is. This

8:04

is part of the story that I'm

8:06

writing about. How do you find out

8:08

about these things that are lost or

8:10

almost lost? And then the big change

8:12

from my point of view is in

8:14

the late Roman period, when two things

8:16

happen, the material for writing changes from

8:19

papyrus to parchment. It's rather nice because

8:21

when a new technology comes along, people are often

8:23

thinking, how does it relate to the old technology?

8:25

Is it the same kind of thing or not?

8:28

And I came across a reference

8:30

in a monastic chronicle. When he's

8:32

first using parchment, he calls it

8:34

animal papyrus, which I thought was

8:36

rather nice because you're interpreting it from what

8:38

you know. And of course, it's not papyrus,

8:40

it's animal. But that's the thing that strikes

8:42

it. And the other thing that happens at

8:44

exactly the same time is that people move

8:46

from the scroll to the codex.

8:49

That is the book that we're

8:51

familiar with, with pages that you can turn

8:53

and a spine that it's so into and

8:55

so on. And that has all sorts of

8:57

advantages, including the protection of the material and

8:59

the fact that you can go to any

9:02

page you want very quickly. So it's quite

9:04

different material. And that age of the parchment

9:06

codex is the middle ages. And then for

9:08

the next thousand years or so, that's the

9:10

standard book. There are exceptions. You can clearly

9:13

make rolls out of parchment. It's quite easily

9:15

done. And the English Royal Administration,

9:17

for some reason, that was the main form

9:19

in which they kept their records. So it's

9:21

not that you can't make rolls, but that

9:23

was the main form in books and libraries,

9:26

down to the invention of printing in the

9:28

15th century, when a whole new world opens

9:30

up. Yeah. And so I guess parchment still

9:32

maintains that vulnerability to fire and water, but

9:34

in the form of a codex, it has

9:37

a degree of protection in that it's closed.

9:39

And those leaves within it, those folios inside,

9:42

can be kind of protected by the

9:44

covers and the folios around them. Yeah,

9:46

you see it most clearly, I think,

9:48

in the case of those fabulous illuminated

9:50

manuscripts, because they've been protected by the

9:52

book being closed and stored somewhere. It's

9:54

not open to the elements all the

9:57

time. And sometimes some of those illustrations

9:59

they looked like they were done yesterday.

10:01

They're beautiful, absolutely beautiful. That's definitely one

10:03

of the things. But you're right, parchment

10:05

is vulnerable to fire. It

10:07

is much tougher than either

10:09

papyrus or paper. The actual

10:11

parchment material is something

10:14

that is pretty tough. It stands up

10:16

to handling. It can indeed

10:18

be burned. You need quite a big

10:20

fire to burn a parchment book. You

10:22

can't do it easily on a bonfire.

10:25

That sounds dangerously like you've tried, Robert.

10:27

I don't want to get into trouble.

10:30

This is a thought experiment. Let me say

10:32

this is a thought experiment. That's why the

10:34

case studies that I've taken all involve modern

10:37

explosive technology, the high technology of

10:39

destruction. Because one of the things

10:41

that the book is about is

10:43

the way that just as

10:46

scholars studied this material and

10:49

archivists gathered it, there was also at

10:51

the same time fantastic development in the

10:53

technology of destruction and warfare. And that's

10:55

where these two things coincide with the

10:57

case studies that I have. One

10:59

of the other things I found really interesting that you

11:01

detail is a little bit about how we have an

11:04

idea of how many manuscripts there might ever have been.

11:06

So how fast could someone compile

11:08

one of those manuscript codexes? A

11:10

monk sitting in cloisters. So what

11:12

do we know about how quickly

11:15

they could physically write one of

11:17

these manuscript codexes? Well, there is

11:19

evidence. One I cite is of

11:21

someone who actually he recorded

11:24

the fact himself in the manuscript he's copying

11:26

out. He's copying out a very big history

11:28

of France in front of the Chronicles of

11:30

the French Kings all put together. It's very

11:32

large. First of all, he recalls that he's

11:34

quite old. So I had a lot of sympathy with him.

11:36

And secondly, that he's working away with this stuff. And he

11:39

tells you how long it took to do it. So

11:41

he tells you exactly how long it took to do

11:43

it. The manuscript survived so we know how long it

11:45

is. So you know how long

11:47

copying out that amount of material took. You

11:50

have to make some assumptions, about

11:52

did he work every day, etc. So

11:54

that would be one. And another one

11:56

I rather like is there's a famous

11:58

author called Christine de Pison. She

12:00

was Italian origin but working in France. And

12:03

she is often described, and I think with

12:05

some justification, as the first professional

12:08

female writer, she is a

12:10

full-time writer. And rather

12:12

unusually, she's not only a writer in the

12:14

sense of composing written works, but she actually

12:16

copies them out with a pen herself. We

12:19

know that. And there's a manuscript surviving copied

12:21

out by her, which she's copied out. A

12:23

gathering is a number of folios bound together.

12:25

There would be like six or eight of

12:27

these folios. And she's very proudly at the

12:29

end of one, she said, I copied out

12:32

this whole gathering in one day. She's very

12:34

proud of that. And that's her handwriting, of

12:36

course, because we know that she was writing

12:38

it. So you've got little indications of

12:40

the speed. And then of course,

12:42

the other thing that you have to build in, if

12:45

you're thinking about how much material there was, not

12:47

simply the speed of one scribe, but

12:49

how many scribes there are, and how

12:52

common is the ability to write, because

12:54

the ability to read and the ability

12:56

to write are separate things. And

12:59

they were regarded as separate skills. And I

13:01

think many more people have the ability to

13:03

read and the ability to write. It was

13:05

seen very much as a manual exercise, you

13:08

know, for the monks, they have a phrase

13:10

to work is to pray, labra re esto

13:12

re re. So actual physical work is deemed

13:14

to be some kind of almost religious activity.

13:17

And writing out books would definitely qualify as

13:19

that kind of work that is also prayer.

13:21

So you've got the number of people. And

13:24

then you've got little changes things, for example,

13:26

like what kind of script is there? Do

13:29

you have joined up script cursive? Or do

13:31

you have the script where the letters are

13:33

separate? And it's pretty clear that writing in

13:35

cursive is faster to do than writing where

13:37

all the letters are separate. And then the

13:40

final thing is that towards the end of

13:42

the Middle Ages, paper makes its appearance in

13:44

Europe, it had been around in China for

13:46

hundreds and hundreds of years, it

13:48

had then come to the Islamic world. And

13:51

from the Islamic world, it finally came

13:53

to the Western Christian world. And

13:55

you have the beginning of production of

13:58

paper mills in Spain and France. that's

22:00

no longer interested at all in

22:03

manuscripts of the aristocracy because you want to

22:05

get rid of the aristocracy. That doesn't happen

22:07

all that often, but it does happen. Real

22:10

revolutionary change. And you think of the countries

22:12

where it has happened, such as France is

22:14

a good example, obviously, because the French Revolution

22:17

was so dramatic. And then the countries where

22:19

there has never been quite that clean

22:22

slate. England is a very good

22:24

example because the English medieval records

22:26

are amongst the best in Europe

22:28

because of that continuity. And

22:30

you can understand how ideology

22:33

fits into this. If you've got an ideology

22:35

like we're making a fresh start now, the

22:37

records of the past are not important. If

22:39

you're looking at, as many people did, if

22:41

you're looking at English history as

22:43

a continuing story of

22:46

the nation and so on, then

22:48

the national past is very important.

22:51

And that's why you have in the

22:53

19th century, particularly, but subsequently as well,

22:56

government funding for the

22:58

examination and publication of medieval sources. And

23:00

it's regarded as a national task in

23:03

some ways. And you'd find that in

23:05

other countries as well. After

23:22

Dark, Myths, Misdeeds and the Paranormal

23:24

is a podcast that delves into

23:26

the dark side of history. Expect

23:30

murder and conspiracy, ghosts

23:32

and witches. I'm

23:35

Anthony Delaney. And I'm Maddie Pelling.

23:37

We're historians and the hosts of

23:39

After Dark from History Hit, where

23:41

every Monday and Thursday we enter

23:43

the shadows of the past. We

23:45

set sail on Victorian ghost ships.

23:47

Learn the truth about the Knights

23:49

Templar. And walk the grimy streets

23:51

of Victorian London in search of

23:53

a serial killer. Discover the secrets

23:56

of the darker side of history

23:58

twice a week, every week. Hey.

24:35

I'm Ryan Reynolds recently I us Mint

24:37

Mobile legal team if big wireless companies

24:39

are allowed to raise prices due to

24:42

inflation. They said yes And then when

24:44

I asked if raising prices technically violates

24:46

those onerous to your contracts, they said

24:48

what the fuck are you talking about

24:50

you Insane Hollywood As so to recap,

24:52

we're cutting the price of Mint Unlimited

24:54

from thirty dollars a month to just

24:56

fifteen dollars a month. Give it a

24:59

try! Mint mobile.com/switch. Forty five dollars a front that humans

25:01

must have to the these permanent new customers for them to time unlimited

25:03

wasn't pretty good bye to come on South Pole! Turns out Mint mobile.com.

32:00

were not destroyed in 1922 because they

32:02

were still in the possession

32:04

of the monastery of Clantonie. And

32:06

in the end, they went into private hands

32:09

and from there to the present day National

32:11

Archives. So you can go to

32:13

Kew, which is where the National Archives are as

32:15

you know, and sit there. And you've got a

32:17

complete description of exactly what you're

32:19

talking about, the lives of ordinary people in

32:22

mainly county meat, what their rent was, what animals

32:24

they had, what duties they had, how much land

32:26

they had, the families and so on. So there's

32:28

tiny little ways round. It's not as if the

32:31

loss is total. I mean, the loss is enormous,

32:33

but you've still got ways of kind of finding

32:35

what you can. It was the anniversary in 2022

32:37

of that destruction. And

32:39

it's a famous incident in Irish history. There's

32:42

been a long term project to see what can be done.

32:45

And they now have a website you can

32:47

go to in which they recreated an image

32:49

of the Public Record Office of Ireland as it was in 1922.

32:53

And you can go into that and you

32:55

can look in the area where particular records

32:57

were kept. You can look on

32:59

the area where the Exchequer Records were or the Chancery Records or what

33:01

it might be. And that will lead

33:03

you to a list and a description of all

33:06

the things that could be used now to supplement

33:09

the stuff that was lost. Sometimes

33:12

it's duplicates that were sent to England. Sometimes

33:15

it's transcripts that were made by scholars before 1922.

33:18

It's an amazing achievement because of course

33:20

I'm writing about terrible loss. So it's good to

33:22

have an occasional kind of upbeat story there. A

33:24

little bit of hope, a little pimp rig of

33:26

light in the darkness of all of the loss.

33:30

Slightly unfair and mean question maybe.

33:32

Of your five case studies, if you could undo one

33:35

of them and have all of those records back, which

33:37

one would you undo? Well

33:39

I think the answer

33:42

would probably have to be Dublin

33:45

because that was

33:47

the biggest loss of

33:50

continuous documentation of

33:52

which in many cases there's no

33:55

other copy. So there's no substitute. There

33:57

are sometimes duplicates that were sent to

33:59

England. England, but that's only for a

34:01

minority of cases. And

34:03

in two of the cases, I

34:05

actually concentrate on a particularly remarkable

34:07

document, an individual document that was

34:09

lost in the case of this

34:11

Schellingen Strasburg in 1870. I look

34:13

at a particular illuminated manuscript, the

34:15

Garden of Delights, the Hautostelichiarum, which

34:17

is a fabulous late 12th century

34:19

illuminated manuscript, very, very beautiful. And

34:21

we know about it in various

34:23

ways. That would be great

34:25

to have again, but that's one thing. And

34:28

similarly with the bombing of the state

34:30

archive in Hanover, by the RAF during

34:32

the war, second world war, the loss

34:34

of the thing called the Ebsdorf map,

34:37

which is a mapamundi that is a map of

34:39

the world. And people are often familiar with the

34:41

Hereford mapamundi, the

34:43

Ebsdorf mapamundi, which was destroyed in

34:46

bombing was vast. It was 12

34:48

feet by 12 feet. The

34:50

Hereford mapamundi is made from one animal

34:52

skin, and the Ebsdorf one is made

34:55

from 30. So you

34:57

can see the difference in scale. It was

34:59

obviously the largest mapamundi of which we have

35:01

knowledge in the Middle Ages. And that of

35:03

course, would be a wonderful thing to have.

35:05

The Ebsdorf map, particularly, is a loss

35:07

in many ways, but particularly because as

35:10

the technology for

35:12

analyzing and exploring documents

35:14

and manuscripts of the past gets more

35:16

and more sophisticated, and it's getting more

35:18

and more sophisticated all the time. I'll

35:21

give the example of a late 12th

35:23

century beautiful manuscript from Spain. It's a

35:25

collection of charters, royal charters, but it

35:27

also has pictures of all the kings

35:29

and queens of Spain, of Aragon. And

35:32

the art historians are quite clear that this document

35:34

was compiled over quite a long period of time.

35:37

And they see that there's kind of changes in

35:40

the style of the images of the

35:42

rulers that are painted in there. So it suggests that that

35:44

some are earlier and some are later. And

35:46

much more recently, in very recent times,

35:49

they now have a technology called

35:51

X-ray fluorescence, which enables

35:54

them to analyze the chemical

35:56

makeup of pigment to a

35:58

fantastically sophisticated degree. and

40:00

fast movements. I think it's very

40:02

clear that the Carolingian period, around

40:04

about 800 to

40:06

900, that the amount

40:08

of copying of earlier manuscripts

40:11

suddenly boomed. I think in

40:13

many cases, if you haven't

40:16

got the work copied in

40:18

that period, it's probably not going

40:20

to survive. It's a very narrow bottleneck. The

40:22

example I choose to discuss is the poet

40:25

Lucretius. Lucretius was active in

40:27

the first century BC. His

40:29

poem is one of the

40:32

longest statements of

40:34

a purely materialist philosophy

40:36

we've got. He thinks

40:38

there is nothing in the universe except

40:40

atoms and the void. He thinks the

40:42

idea of God's making the world is

40:44

ludicrous. He thinks that after you die,

40:46

you die. It's a very

40:48

radical materialist philosophy. The only reason we

40:50

know about that poem is that two

40:53

monks copied it out in

40:55

the time of Charlemagne. One of

40:57

them certainly at Charlemagne's court. That's

40:59

really remarkable in itself. That's something

41:02

that has come through from the ancient world,

41:04

but there's no copy of it that we

41:06

know of. The earliest surviving record is 800

41:09

years after it was composed. It seems

41:11

that those two manuscripts were not copied

41:14

for most of the Middle Ages. No

41:16

one in the Middle Ages really cites

41:18

or knows Lucretius. It's just gone. Then

41:20

at the very end of the Middle

41:22

Ages, there's an Italian Renaissance figure, Poggio,

41:25

who loves manuscripts. He's a manuscript hunter.

41:27

He finds a copy, and then it

41:30

can be copied out. Then it can

41:32

go into print, and then

41:34

it can be read by the learned people

41:36

of Europe and has been ever since. It

41:40

just made it through. We would

41:42

have known nothing about that fantastic

41:44

materialist epic unless it had been

41:46

for the monks at Charlemagne's

41:48

court. What the monks were thinking when they copied

41:50

this stuff out, we don't know. Yeah, I think

41:53

that the same is true with things like Beowulf,

41:55

isn't it? You don't expect those kinds of pagan

41:58

or, I don't know, say... documentaries

50:00

when you subscribe at historyhit.com/subscribe.

50:02

And as a special gift

50:05

you can get 50% off

50:07

your first three months when you use

50:09

the code MEDEVIL at checkout. Anyway,

50:12

I better let you go. I've been Matt Lewis

50:15

and we've just gone MEDEVIL with History Hit. To

50:24

make switching to the new boost mobile

50:27

risk-free we're offering a 30-day money-back guarantee.

50:29

So why wouldn't you switch from Verizon

50:31

or T-Mobile? Because you have nothing to

50:33

lose. Boost mobile is offering a 30-day

50:35

money-back guarantee. No, I asked why wouldn't

50:37

you switch from Verizon or T-Mobile? Oh.

50:39

Wouldn't. Uh, because you love wasting money

50:42

as a way to punish yourself because

50:44

your mother never showed you enough love

50:46

as a child. Whoa, easy there. Yeah.

50:48

Applies to online activations, requires port in

50:50

and auto pay. Customers activating in stores

50:52

may be charged non-refundable activation fees. To

50:55

save power, I'm going to talk super fast to finish before our flex

50:57

alert starts. All we have to do is use less power during a

50:59

flex alert to help keep the lights on. I can't stop acting this

51:01

fast. Why not? I unplug the fridge and drink all the ice coffee.

51:03

Nobody needs to unplug the fridge. Okay, okay, okay, okay. Or drink two

51:05

gallons of ice coffee. The

51:07

power is ours with flex alerts.

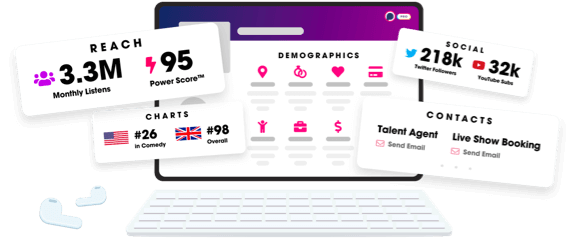

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us