Episode Transcript

Transcripts are displayed as originally observed. Some content, including advertisements may have changed.

Use Ctrl + F to search

0:06

Hello and

0:08

welcome to the Feeling Good podcast where

0:10

you can learn powerful techniques to change

0:13

the way you feel. I am your

0:15

host, Dr. Rhonda Baravsky, and joining me

0:17

here in the Murrieta studio is Dr.

0:19

David Burns. Dr. Burns is a pioneer

0:22

in the development of cognitive behavioral therapy

0:24

and the creator of the new team

0:26

therapy. He's the author of Feeling Good,

0:28

which has sold over 5 million copies

0:31

in the United States and has been

0:33

translated into over 30 languages. His latest

0:35

book, Feeling Great, contains powerful new techniques

0:38

that make rapid recovery possible for

0:40

many people struggling with depression and

0:42

anxiety. Dr. Burns is currently an

0:45

emeritus adjunct professor of clinical psychiatry

0:47

at Stanford University School of Medicine.

0:50

Hello, Rhonda. Hello,

1:02

David, and welcome to our listeners throughout

1:05

the world and galaxy. This is

1:08

the Feeling Good podcast, and this

1:10

is episode 406. We

1:13

have our beloved Matt May joining us again. Hey,

1:16

Rhonda. Hey, David. Hey, Matt. Long

1:19

time no see. We're

1:22

starting a practical philosophy month,

1:24

and I'm sure that David will do

1:26

a fantastic job of introducing that. I

1:28

thought I would start by reading an

1:32

endorsement that we got, just a brief

1:34

one, and you could wax philosophical about

1:36

this endorsement. Okay.

1:39

And this is from Al,

1:41

and Al wrote, just briefly, I started

1:44

using the Feeling Good app yesterday. I'm

1:46

so happy it's on my app store in

1:49

Europe. I've already recommended

1:51

it to clients, and I've

1:53

received positive feedback regarding its

1:55

effects. Al. Oh, awesome.

1:58

Well, thank you, Rhonda. we greatly,

2:01

greatly appreciate that. Yeah,

2:04

for those of you in the US, it

2:07

is available now in the

2:09

app stores and

2:13

may be available soon for web

2:15

also where you can just use

2:18

it on your computer. Oh, wow. So

2:20

we're getting some- How do you know that was an option? Yeah,

2:23

we're getting some good results from it.

2:25

There's a little OB bot and OB

2:27

was my teacher, my cat. My

2:30

beloved one. And he

2:33

can be your teacher too. And then there's

2:35

a lot of classes and lessons. There's some

2:37

cool things in there. And a lot

2:40

of people are getting rapid and fairly

2:42

dramatic reductions in negative feelings from the

2:44

Feeling Great app. So if

2:46

you haven't had a chance, you can take a free

2:48

ride and see if you like it. And then if

2:51

you wanna purchase a subscription for

2:54

a year, it's not

2:56

very expensive. And

2:58

if you can't afford it, just contact us and

3:01

we'll give it to you for free. We don't

3:03

want anyone who wants it to not be able

3:05

to get it and use it. And

3:10

one other quick commercial message, and we'll

3:12

make this one real

3:14

short, but the intensive is

3:17

coming up August 8 to 8, 9, 10, 11. That's

3:21

Thursday, Friday, Saturday. And

3:24

there'll be two evenings there and

3:26

then Sunday until noon. The South

3:28

San Francisco Conference Center. And

3:30

it's the first time we're doing

3:32

an in-person intensive in five years

3:34

because we had to give up

3:36

during the COVID pandemic.

3:39

So we're bringing it back. And

3:41

it's our greatest teaching

3:45

of the year. And so if

3:47

you'd like to learn about team from

3:49

A to Z and learn how to

3:51

do this high speed treatment of patients

3:53

and get, you've heard Rhonda

3:55

and David and Man and David

3:57

and Jill and David on podcasts.

4:00

You hear people in two hours

4:02

getting a complete elimination of symptoms

4:04

and that's what team

4:07

is aiming for with

4:09

people who are depressed and anxious. And if you'd

4:11

like to learn how to do that, that's what

4:13

we're going to teach at the South San Francisco

4:15

Intensive. Plus, you'll be able

4:17

to work on your

4:20

own issues too because that's part

4:22

of becoming not only

4:24

a good therapist, but to say

4:26

nothing of becoming a great therapist.

4:28

You've got to have done your

4:30

personal work and found your own

4:33

personal enlightenment. So you'll have

4:35

a chance to do that there too.

4:37

Where do they go to find out

4:39

about it, Rhonda? They

4:42

go to www.cbtintensive.com.

4:49

So www.cbtcognitivebehaviortherapy.com,

4:51

but just

4:53

see letter B,

4:56

letter T intensive.com.

4:59

And then you'll get all the information there.

5:02

So hope to see you. You can come

5:04

in person. If you

5:06

want to come in person, move fast because

5:08

the seating is strictly limited to 120 and

5:10

it's filling up very rapidly, especially

5:15

by the time this this

5:18

podcast comes out, there's likely

5:21

to be very few

5:23

live seats available. You can also

5:25

come online at a

5:28

50 percent discount. So

5:30

if you're in India or wherever, you don't

5:32

have to travel as you've had to in

5:34

the past. We never had it

5:36

online before. So you can come

5:38

online or in person and it's going to be a

5:41

terrific four days

5:43

for you. So hope to see you.

5:47

OK, David, we're starting the

5:49

Practical Philosophy Month. Can you explain what

5:51

that is? Yeah,

5:55

the the the Practical Philosophy

5:57

Month is that it's. started

6:00

out, you know, I was

6:02

a philosophy of science major at Amherst

6:04

College and I was always, you

6:07

know, challenged by these

6:10

philosophical problems like do humans

6:12

have free will or is

6:14

there such a thing as the self or

6:16

is the universe real or is the universe

6:19

one and things of that nature.

6:21

And I read a book

6:24

by my senior year by Ludwig

6:28

Wittgenstein, the Austrian philosopher

6:32

and one of my college

6:35

roommates told me to read it, Phil Allen,

6:37

he was a physics major and he was

6:39

incredibly brilliant to say nothing of the fact

6:41

that he was one of the humblest, nicest

6:44

guys around. But

6:47

he was really brilliant and I was trying to figure

6:50

out what to do my honors

6:52

thesis work or whatever you call it

6:54

your senior year in college. And

6:57

he said, well, there's this book

6:59

by Ludwig Wittgenstein and you

7:01

could do your dissertation on that or

7:04

your thesis. And he

7:06

said, it's really cool because there's

7:09

two things about it. Number one,

7:11

it's rumored that it contains the

7:14

solution to all the problems of

7:16

philosophy. And it

7:18

came out in 1950 right

7:20

after Wittgenstein died. But

7:23

the other thing about it is it's rumored

7:25

that there's only seven people in the world

7:27

who can understand Wittgenstein.

7:30

And so if you can read that

7:32

book and understand it and write your

7:35

dissertation on it, when you have

7:37

to defend it, defend your honors

7:39

thesis or whatever, they

7:42

won't be able to challenge you because there's

7:44

probably no one on the faculty who understands

7:46

that book. So you'll

7:48

be kind of in the driver's seat. So

7:51

I thought, man, that sounds so cool. And

7:53

so I picked up that

7:56

book, Philosophical Investigations, and

7:59

I read it and I I studied it and

8:01

I couldn't understand it.

8:04

But it was about very simple things.

8:07

Like, it was

8:09

just a series of numbered

8:11

paragraphs. It wasn't even a book, it was

8:13

just notes they found under his bed

8:16

and a metal box under

8:19

his dormitory room in Cambridge University

8:22

where he taught toward the end

8:24

of his life. It was

8:27

notes that he had for this

8:29

weekly seminar. And he

8:31

put them in there thinking if they

8:33

had any value and the building burned

8:35

down, maybe someone would find that metal

8:37

box and find the notes and find

8:40

them of value. But he

8:43

struggled with depression, which

8:45

makes me very sad. And

8:49

he was considered, many

8:51

people considered him the

8:53

most brilliant man in

8:55

Europe. And his

8:57

father was the wealthiest man in

8:59

Europe. And

9:02

when his father died,

9:04

he became like the

9:08

Rockefeller of Europe. He was the wealthiest

9:10

man in Europe. And he gave all

9:12

of his money away in about a

9:14

week or something like that, because

9:16

he thought it would be the

9:19

source of evil or something like that. And

9:23

he never published anything

9:25

when he was alive. And

9:28

he suffered from severe depression. And

9:31

he had three brothers who, he

9:33

had four brothers and three of them

9:35

committed suicide. And he

9:37

spent much of his life in

9:40

suicidal depression. And

9:44

he thought when he was depressed

9:46

that his work was rubbish. And

9:50

now he's become known,

9:55

probably the greatest philosopher who ever

9:57

lived. But

10:00

I couldn't understand that book. And

10:03

it was just about kind of trivial

10:06

things, like the word game. He

10:08

was saying, think about the word game. Now,

10:12

what's the essence? What's the true meaning

10:14

of the word game? And

10:17

he says, well, what do you have to have to

10:19

be a game? And he says, well, maybe you have

10:21

to have two teams. Is

10:24

that the essence of a game? Two

10:26

competing teams. He says,

10:28

but then you've got a game like Solitaire. There's

10:31

not two teams, there's not even a team.

10:33

There's just one person. But

10:36

then how about the dating game? And

10:40

then how about the game of life? Or

10:44

we say of someone, he's

10:46

a boxer. He's really a game

10:49

boxer. And you

10:52

think of all these different words, the

10:57

names of the word game. And

11:00

some have overlapping meanings and some

11:02

don't overlap with any of the

11:04

others. And those are just all

11:06

the ways we use that word game in the English

11:09

language. And then he would say, are you ready

11:11

now to give up the free will problem? And

11:14

I would be thinking, not

11:17

really, dude. I don't even know what the hell

11:19

you're talking about. And

11:21

there were all these little numbered

11:23

essays. He

11:26

says, think about a

11:28

bricklayer. What is a bricklayer? Imagine

11:31

there's a master bricklayer. This is how he started

11:33

the book. And he

11:36

has an apprentice who's helping him. And

11:38

he's building this beautiful brick wall. And

11:41

every now and then he shouts brick.

11:43

And then the apprentice

11:45

brings him another stone to

11:48

add to the wall. And

11:51

he says, that's all they're really doing.

11:53

He's the old guys building this wall

11:55

and the apprentice is learning and

11:57

handing him bricks or stones when he

11:59

needs them. And then he

12:01

says, now where you see the error that Aristotle

12:03

made 2,000 years ago or 2,500 years ago. And

12:09

I would think, no, I don't.

12:11

I don't have any idea what you're

12:13

talking about. And then he'd go on

12:15

to another little essay. And he'd say,

12:18

my only dream in life was to

12:20

write a philosophy

12:22

book that consisted of nothing

12:24

but jokes. But

12:27

the tragedy of my life is I never had

12:29

a sense of humor. And

12:32

I read that. I thought that was really funny

12:34

because a lot of his little essays, once you

12:36

understand them, they are like jokes. They are funny.

12:39

But I just couldn't understand the book.

12:41

And spring came and, you know, it

12:43

was getting time to do my dissertation.

12:46

And I was walking across Amherst

12:48

campus and I saw some fellows,

12:51

you know, throwing snowballs through an

12:54

open window. It was really mean.

12:56

And I just got

13:00

really, really angry. And then

13:02

I suddenly saw what Wittgenstein had been

13:04

saying. And I saw the solution to

13:07

all the problems of philosophy that I

13:09

had been plagued by. And

13:12

so Wittgenstein's dream

13:14

was that if his students would only

13:16

understand what he was trying to say,

13:18

they'd give up philosophy. So

13:21

that's why I gave up philosophy, was

13:23

because of Wittgenstein. And I went to

13:25

medical school. He thought you should do

13:27

something practical. And I always wished

13:29

I could have written to him or

13:31

talked to him when he was alive

13:34

and said, I understand that no

13:36

one understood you and your students didn't

13:38

understand you. And I can

13:41

imagine how lonely you were. But I want

13:43

you to know I got it. It took

13:45

me six months to figure out what you were trying

13:47

to say, but I got it. And

13:49

so I gave up philosophy. And

13:53

I hope you'd be proud

13:56

of me because I did

13:58

something practical. I went to

14:00

medical school. I wasn't a

14:02

pre-med student, it was horribly

14:04

uncomfortable for me, but

14:06

I made it through. But

14:09

then later on I came to

14:11

realize that the cognitive therapy

14:13

I got so involved with

14:16

was very much like Wittgensteinian

14:18

thinking. And

14:20

that it has made a tremendous

14:22

impact on my life and my

14:24

thinking. And

14:27

so I thought it would be fun

14:29

to have a practical philosophy month and

14:31

talk about how Wittgenstein would have solved

14:34

these problems. Because

14:36

he didn't view philosophy

14:39

as valid, he viewed it as

14:41

mental traps that people get into,

14:43

much like people with obsessive compulsive

14:45

disorder, obsessive things. And

14:48

he was trying to develop a treatment

14:51

for philosophers to be able

14:53

to let go of these things with good

14:55

reason, to see why and how to let

14:57

go of them. But

15:01

that's the same really that I'm doing

15:03

when I'm working with people with depression

15:05

and anxiety disorders.

15:09

Cognitive therapy is also all

15:12

about thinking errors. And

15:14

Wittgenstein kind of pointed the

15:16

direction for that. But

15:19

I've always been sad because he

15:22

never figured out how to use

15:25

his philosophical breakthroughs on

15:27

his own thinking. And

15:29

that didn't develop until after he

15:31

died. And shortly after he

15:33

died, then Albert Ellis in New

15:35

York developed his rational emotive therapy,

15:37

which was a huge

15:41

shift from psychoanalysis, a radically different

15:43

way of doing therapy. And then

15:45

Beck kind of copied Albert Ellis,

15:47

and he called it cognitive therapy.

15:51

But all of this work

15:53

was flowing naturally from the

15:55

work of Wittgenstein. And

15:58

those philosophical problems... still plague

16:00

people today because people today

16:03

still have trouble understanding Wittgenstein.

16:06

And he was kind of like the Buddha. People

16:09

can't understand him because it's so simple what

16:11

he's trying to say. And it's

16:14

so basic that it's almost like

16:16

invisible to people. And I can

16:18

understand his loneliness and his frustration

16:21

when he was alive. But

16:23

it's the same thing that when

16:26

we're working with patients, trying to get

16:28

them to see what they're telling themselves

16:31

doesn't make sense. Like I'm a worthless human

16:33

being. I'm not good enough. I'm

16:35

inferior. And so

16:38

I thought we'd attack some of these classic

16:42

philosophical problems but put it into

16:44

a practical sense so it's not

16:46

just philosophical nonsense for people. But

16:49

you can see if you're struggling

16:51

with depression or anxiety how this

16:53

might have something in it for

16:55

you. And also

16:58

how this kind of bizarre

17:02

philosophical thinking has

17:04

permeated like the DSM and

17:07

the way the

17:09

established psychiatric profession thinks

17:12

about patients and

17:14

how it has a kind of

17:16

potentially a negative impact

17:18

there as well. So there's a

17:20

lot of practical implications

17:24

from all of this. And so today

17:26

we're going to kick it off with

17:28

the free will problem. And

17:32

I'll briefly state

17:36

two ways of thinking about the free will

17:38

problem. And then we'll get into BSing about

17:40

it and stuff like

17:43

that. And maybe

17:45

have some fun with it. But you know

17:47

all of us we think we have free

17:49

will. Like you see this this

17:51

pan I think I'm just going to drop it. And

17:55

I did that and it fell on my clipboard.

17:58

And so I have the

18:00

idea, I did that of my

18:02

own free will. But

18:05

then for hundreds

18:07

of years, people have

18:10

struggled with this and thought, well, but how can

18:12

we have free will? And

18:14

there is a scientific aspect

18:17

of the problem and a religious

18:19

aspect of it. The scientific aspect

18:21

is that we all have

18:25

to follow the rules of physics or the

18:28

laws of the universe. And

18:32

we're doing that at every moment of every

18:34

day. And so like

18:36

even now, my brain is causing

18:38

me to

18:44

do what I'm doing. And

18:47

I can't violate any of the laws

18:50

of physics. And therefore, I

18:52

have to be doing what I'm doing at

18:55

every moment. And therefore, I can't have

18:57

free will. That's one version

18:59

of it. Now you can concoct

19:02

that in a lot of ways.

19:04

And Matt, you have a cool

19:06

way of explaining it also, which

19:10

we'll get to in a minute. But

19:12

then another version is the religious version. You

19:15

know, when I was little, I was

19:17

a minister's son. And

19:19

so I was taught that God is omniscient,

19:24

omnipotent, and

19:27

all-knowing. And omniscient means,

19:31

oh, no, omniscient, omnipresent, and

19:35

well, all-powerful. I'll just say

19:38

the simple words. God is

19:40

all-powerful. God is everywhere. And

19:42

God knows everything. And so

19:45

religious people have said, since God

19:47

knows the past, present, and future,

19:50

God knows what we're going to do at

19:52

every minute of every day. And we can't

19:55

do anything other than that. And therefore, we

19:57

have no free will. That's the free will

19:59

problem. And later on I'll

20:01

tell you, you know, what

20:03

I consider to be the solution to

20:05

that and the other problems of philosophy.

20:09

But that's it. And so we

20:11

could start there, but just to

20:13

say right off the top that

20:17

the one emotional

20:20

aspect of this is that

20:23

a lot of times people feel

20:26

extreme guilt. There's

20:28

some screw up you did in the past. And

20:32

like a woman came to me early

20:35

in my practice, her brother

20:38

had committed suicide. And

20:40

she thought she should

20:43

have known he was suicidal on

20:45

that day. And

20:47

so she told me that therefore it's

20:50

my fault that he died, that I

20:52

didn't save him. And therefore

20:54

I too deserve to die. And

20:57

so she was also considering killing

21:00

herself. And that

21:02

would be an extreme example of

21:05

guilt when we're blaming ourselves. But

21:09

if we don't have free

21:11

will, then perhaps we

21:13

can say, you know,

21:15

I couldn't have been doing differently from what

21:17

I was doing that day. And

21:21

therefore it's not my fault. And

21:24

it may be a way of escape from

21:26

her suffering. The other potentially

21:29

useful application, if you

21:31

think of it that way, is people

21:33

who were going to rages, road

21:36

rage, or rage at

21:40

people who were different and want to kill

21:42

other people. And

21:45

then we get mad at them saying they shouldn't

21:47

be like that. They shouldn't have

21:49

those values that they have. But

21:52

then you can think, well, that's like saying a

21:55

lion shouldn't kill a deer when

21:57

it's hungry. Lions are

21:59

programmed. to do that. And

22:01

similarly, we're programmed to do what we

22:03

do. And therefore, just

22:06

as lions can't escape all of the

22:09

hundreds of millions of years of

22:11

evolution and programming that they've had,

22:14

we can't either. And therefore,

22:16

people can't be doing other

22:18

than what they're doing. And

22:20

therefore, we can accept

22:23

with sadness, you know,

22:26

bad behavior and others, but

22:28

it's nonsensical to be

22:30

judging people because they don't have

22:32

free will. So those would be

22:34

some beginning to dip into

22:36

kind of an ocean of relevance

22:39

of some of these philosophical

22:41

problems to emotional issues.

22:44

And at this point, I will

22:46

now shut up having talked too

22:48

much, but that's kicking off our

22:51

practical philosophy month. And we'll try

22:53

to talk about these things on

22:55

the philosophical level, on the emotional

22:58

level, and then on the level

23:00

of the way psychiatry and psychology

23:02

are structured and perhaps not the

23:05

best way. And

23:09

so now I will turn it over to my two

23:13

fantastic colleagues. David,

23:18

that was brilliant. I

23:20

share your experience trying to read Wittgenstein

23:23

and philosophical investigations.

23:27

Oh, yeah. Did you feel that same

23:29

frustration? Yeah,

23:31

did you get it right away? I was

23:34

extremely frustrated. I

23:37

stepped around a lot trying to get where's the point

23:39

here? Yeah, yeah, right. Me too.

23:41

You know, do you just flip through the

23:43

page? It doesn't make any difference because they're

23:46

all unrelated, all those numbered things. Right. The

23:49

one that actually helped me was when he

23:51

said, why is it that

23:54

the road that goes up the hill is

23:57

the same as the road that goes down the hill?

24:04

And I kind of got it there and I

24:07

highlighted that part of the book and sometimes go

24:09

back and reread it. But

24:12

yeah, thanks for kicking off philosophy. Is

24:16

it month or? Yeah, yeah.

24:18

Practical philosophy month. Great.

24:21

And we're doing some stuff on free will.

24:24

Free will. I had a list of them.

24:27

But one of the one was,

24:29

does God exist? And then

24:31

do you have the list of them? I

24:36

can pull it up here, actually.

24:39

Yeah, that's a good one. And you

24:41

actually helped me more than the book

24:44

understand Wittgenstein. When

24:46

you summarize simply that you can't

24:48

answer a meaningless question. Yeah.

24:51

That if the terms haven't been defined

24:54

or if it's not used, that you can just

24:56

be kind of

24:59

cheating at the language game. Yeah. Is

25:02

that what dawned on you when you

25:04

saw people throwing snowballs through a window?

25:06

Well, I couldn't. I never connected it.

25:08

But he got his first insight when

25:10

he was walking past a soccer game.

25:12

Because see, he had written this book

25:14

as a teenager that he

25:17

sent to Bertrand Russell. And then Bertrand

25:19

Russell distributed it

25:21

throughout Europe, thinking it was some great

25:23

thing. It was

25:25

impossible to understand, called Tractatus

25:28

Logico-Philosophicus. But

25:30

Bertrand Russell said this is some

25:33

kind of incredible genius. And

25:35

that book spurred a lot of

25:37

the 20th century philosophy

25:40

movements. But

25:42

Wittgenstein left, you know, once he

25:44

sent that to Bertrand Russell, he

25:46

thought he'd solved all the problems

25:48

of philosophy. And so he

25:50

was trying to get out of philosophy because

25:53

it was like an obsession with him. And

25:57

he was... Like the mafia. Yeah,

26:01

that's right. And

26:04

then he went on to

26:06

try to live a

26:08

practical life. And he

26:10

tried to teach

26:13

schoolchildren. And

26:16

he had never finished college. They

26:19

were so wealthy. He had tutors when he

26:21

was a child, but then he didn't so

26:23

much go to schools. And

26:26

he tried to teach grammar school.

26:28

And he got fired because he

26:30

was violent with the kids, because

26:33

they couldn't understand him either. And

26:36

he would get frustrated. So

26:38

then he thought, I'll live as a

26:40

fisherman. So he moved to Norway and lived

26:43

in a fishing village. But

26:46

he couldn't survive that way because he did

26:48

not have fish. So

26:51

he didn't have to have a whole family to

26:54

live as a professional fisherman

26:57

and things like that. And he was kind

26:59

of just doing

27:01

his thing. And then somebody

27:03

told him that a Swedish

27:07

economic student found a flaw in that

27:10

book that Bertrand Russell had been

27:12

distributing, Tractatus Logico

27:15

Philosophicus. And

27:17

he became very depressed at that point because

27:20

he thought it was a correct that

27:23

it was a flaw. And

27:25

so then he went to apply

27:28

at Cambridge to

27:30

be an undergraduate, although he was older,

27:32

because he'd been doing all these

27:35

things to try to find his way in life.

27:38

And so he thought, well, I'll apply

27:40

to be an undergraduate at Cambridge. And

27:45

somebody in the admissions office

27:47

found his admission application

27:52

and brought it to Bertrand Russell

27:55

because they knew Bertrand Russell had

27:57

been wondering who this person was.

28:00

who had sent him this manuscript years

28:02

earlier that Russell thought was so great.

28:05

And then Bertram Russell said, well, bring

28:08

him to my office. And

28:12

so Wittgenstein was excited to meet

28:14

this, famous British

28:17

philosopher who he'd

28:19

kind of idolized. And

28:22

Bertram Russell said, we're sorry

28:25

to tell you that we can't admit you

28:29

to Cambridge. And

28:33

Wittgenstein was very disappointed

28:36

and said, well,

28:38

why not? Why can't I be an

28:41

undergraduate here? And

28:43

Russell said, because you're already recognized

28:46

as the greatest philosopher of

28:48

the 20th century. And

28:52

Wittgenstein said, yeah, but there was an

28:54

error in that book that I sent

28:56

you. And

28:59

that's why I have to study philosophy

29:03

and try to find another way to

29:05

answer these questions. And

29:09

Bertram Russell said, well, no, we're

29:12

gonna give you a PhD for that

29:14

book you wrote. So you won't have

29:16

to go to college or graduate school.

29:19

And we wanna make you a full

29:22

professor in

29:24

the Department of Philosophy. Wittgenstein

29:27

said, no, I can't do that. I

29:29

can't teach in a classroom because I

29:31

don't know anything. What I thought

29:34

I had figured out was wrong. And

29:37

they argued back and forth. And finally

29:39

Bertram Russell made a deal with them

29:41

and said, well, we'll make you a

29:43

fully tenured professor. And

29:47

you won't have to teach in any classroom,

29:49

but you have to have a seminar once

29:51

a week in

29:54

your dormitory room. And

29:56

then anyone who wants to come can come and

29:58

you can do that. can just talk to people.

30:01

That's all you'd have to do. And

30:04

so he agreed to that. And

30:07

then for the next 10 years, all

30:12

of the famous European

30:14

philosophers would go to

30:17

Cambridge and try

30:20

to cram into his dormitory room. And

30:23

he would have dialogues with them, which

30:25

was like the philosophical investigations you were

30:27

reading. And that's the things he was

30:30

telling people. And he would

30:32

kind of shout at people and get frustrated because

30:34

they couldn't understand what he was

30:36

trying to say. But that's when

30:39

he crafted that book.

30:42

And it was

30:45

sad. He

30:49

developed prostate cancer. And

30:52

I think he thought he maybe didn't

30:54

deserve treatment. He became kind

30:57

of homeless. And

30:59

he finally went to

31:02

a doctor. And

31:07

the doctor said, well, where do

31:09

you live? And he said, well, I

31:11

don't have any place to live. And

31:15

the doctor says, well, you only have a few weeks

31:18

left to live. And

31:22

the doctor said, you can come and

31:24

stay at my house. You can die

31:27

at my house. Wow.

31:29

It was just so

31:31

sad. Yeah,

31:35

it sounds really sad. Because

31:37

he didn't realize the

31:39

impact that he had. And

31:41

now he's viewed by many. And

31:46

he could understand it. As the

31:48

greatest philosopher of all time,

31:50

I think of him as the man

31:52

who killed philosophy, got rid of it.

31:55

He found the answer. But

31:57

it was just so sad. Wow.

32:02

I'm feeling

32:04

very close to you, David. I'm

32:07

feeling very close to you right now, David. Yeah.

32:09

And just in awe of your ability

32:11

to know someone through

32:15

their writings and have

32:18

sympathy and empathy for them. The

32:20

doctor's wife befriended him

32:22

and was with him in his

32:24

dying moments and his last words.

32:28

He just said, well, tell them that I had

32:30

a wonderful life. Wow. But

32:34

he suffered. Also, another

32:36

problem he had, he was gay and it

32:38

was the time when you

32:40

weren't allowed to be gay and there was

32:43

so much shame associated with it. And

32:46

the neat thing about him is

32:48

he loved detective magazines and

32:50

Western movies. And after his seminar,

32:52

he'd rush off to the theater

32:54

and watch a Western

32:57

movie. But

32:59

I don't know if you've been in

33:01

my office. I have his book, Norman

33:03

Malcolm's memoir to him called

33:06

Ludwig Wittgenstein, a memoir. And I

33:09

keep it right there on my shelf with

33:11

this. And you can see him right on

33:13

the cover of that book. And it was

33:15

just a beautiful tribute that his favorite student,

33:17

Norman Malcolm, wrote that book. And that's what

33:19

helped me understand it. That's that

33:22

also helped me when I got that book.

33:25

So how Norman Malcolm talked

33:27

about it. But I'll

33:31

tell you what his insight was and then I'll shut up

33:34

so you guys can talk. But because

33:36

it is so simple, most people, they just

33:38

can't understand it. The

33:42

idea when that soccer

33:45

ball hit him in the head was

33:48

that he thought, well, maybe language

33:50

functions, not

33:52

to name objects in

33:55

external reality, but it's

33:57

we have a series of what you call

33:59

language games. and different

34:02

people use language in different ways

34:04

in different settings. And

34:08

the only meanings of words are

34:10

the way we use them in everyday

34:12

language. And

34:15

what philosophers do is they

34:17

pluck words out of the

34:20

context, the many contexts. So

34:23

they'll try to think, what's the essence of a

34:25

game, the word game, as if there

34:27

is some eternal, correct thing

34:29

that a game is. And

34:32

there isn't anything like that. It's

34:35

just that's game, it's just a sound

34:37

that comes out of your mouth, and

34:40

we can use it in any way we

34:42

want. And when

34:47

you think about it like that, you know, what

34:49

does free will mean? Well, it

34:53

has many meanings. You know, you have

34:56

freedom to vote in America, freedom

34:58

of speech. You don't have so much

35:00

of that in Russia, because if you

35:03

say the wrong thing, you can

35:05

be arrested or killed. I hope we

35:07

don't get to that in America. It's

35:09

heading in that direction, sadly. You

35:12

have free indicating, you

35:14

know, like, you

35:16

know, you buy six bottles of Coke,

35:18

you can get the seventh one for

35:21

free at the local grocery store. They're

35:23

having a sale. We know what that

35:25

means. And,

35:29

you know, the word will, you know,

35:31

has many meanings, many uses. And

35:35

so in all of its natural

35:37

settings, these problems don't exist. Do

35:41

you say, are you free

35:43

to join? Vronda, are

35:45

you free to join us for the Sunday hike,

35:47

one of these days? I sure am. Yeah,

35:50

how about you, Matt? I

35:52

would like to join. Yeah, but

35:55

now we're not talking about some supernatural

35:58

freedom. you know, from the laws of

36:00

science, we're just saying let's get together

36:02

and do some hiking and eat some

36:04

dim sum and just really love being

36:06

with the with each other. That's all

36:08

I'm saying. And that

36:11

is the solution to all the

36:13

problems of philosophy that is

36:16

so basic, you know, people

36:19

don't don't grasp it because they keep

36:21

thinking in this lofty, arrogant

36:23

way that, oh, there's this thing called

36:25

free will or this thing called a

36:27

self, things of that nature.

36:30

And then they try to define these

36:32

things and pontificate about them. And,

36:35

you know, if you ask

36:37

a taxi driver, what

36:39

do you think about the problems

36:41

of philosophy? He'll just tell you,

36:44

oh, well, I'm trying

36:46

to concentrate on getting you to your destination

36:48

right now. Like he'll tell

36:50

you that that sounds like a waste of time.

36:53

And that's a real simplistic way of

36:55

thinking about it. But that's exactly what

36:58

Wittgenstein came up with. It's just language

37:00

out of gear. So

37:05

distracting language, too. It can be

37:08

negative thoughts of all different

37:11

varieties. Yeah. Yeah. And

37:13

be dismantled realizing that all

37:16

this actually doesn't make any it's not

37:18

meaningful language. Am I good enough? Yeah.

37:21

Right. Yeah. Am I good enough?

37:23

Yeah. And but, yeah, we get

37:25

into enchanted by language and then

37:27

we suffer because

37:30

we get trapped by language.

37:32

And that's what depression is

37:35

as well. And we, you

37:37

know, the I feel

37:39

like a loser. I feel like a worthless human

37:41

being way. If we try to define what's a

37:43

worthless human being, it has

37:46

no meaning. It's just

37:49

an empty. It's just

37:51

an empty set there.

37:58

How much do you have to achieve? before you're

38:00

a worthwhile human being.

38:03

It's nonsensical. And

38:06

to let go of these constructs is what

38:08

we're trying to do when we work with

38:10

people. Instead of beating up

38:12

on yourself and telling yourself you're not

38:15

good enough, you've got a life to

38:17

live. Hang out with

38:19

someone awesome like Ronda or Matt,

38:21

or do some fun

38:23

shit like what the Buddha recommended.

38:33

When I think of free will, this is probably completely

38:35

off the subject. I think of advertising and

38:38

how when I go to the store

38:41

and I buy something, I think I'm

38:43

doing it from my own desire. But

38:46

sometimes I'm doing it because I'm being influenced

38:49

and my will is being influenced by the sophisticated

38:53

advertising campaigns that

38:55

guide me toward one product or another. Yeah,

38:58

that's cool to think about. And

39:00

Matt, you're the great expert on

39:02

hypnosis and suggestibility too. And we

39:04

can certainly use the power of

39:07

suggestion to cause

39:10

all kinds of weird

39:13

and crazy experiences in people.

39:17

That's very true. Yeah. So I

39:19

like what you were saying, Ronda, that I

39:21

think they made it illegal to

39:24

insert these many clips into

39:26

movies that showed like a delicious

39:30

looking glass

39:32

of Coca-Cola because

39:37

without people being aware of it, they would

39:39

get the suggestion to go buy some

39:41

Coca-Cola and there

39:43

would be a long line of people suddenly

39:45

right after that little invisible, you

39:47

don't even know you've seen it, suggestion

39:50

that you're thirsty for

39:52

some Coca-Cola. And so I think

39:55

we're constantly being influenced in ways that

39:57

we're not even aware of. has

40:00

drawn into question, is there free

40:02

will? And we'd

40:04

have to define it. I think Wittgenstein

40:06

would be rolling over in his grave right now if

40:09

we didn't try to define what we meant by

40:13

free will, and there would be no

40:15

way to test it either, whether it's

40:17

there or not there, if we

40:20

don't define it. And we may just

40:22

get stumped here. There may not be a way to

40:25

define what that

40:27

is. If

40:32

I were to credit a philosopher today, it

40:34

would probably be Sam Harris. Be

40:37

who? Sam Harris. And

40:40

he wrote a book on this topic

40:42

called Free Will. Oh. Is

40:46

that about the same thing? It

40:49

is. It's very well titled, coincidentally.

40:54

Yeah. What did he have to

40:56

say? One

40:58

of his quotes that I like is that we

41:01

cannot decide what we decide, that

41:05

we can all make decisions. Like you pointed out

41:07

earlier, I can decide to drop this pin or

41:11

not. And I think

41:15

his main idea is

41:18

that you just cannot decide what

41:20

you decide. And

41:24

if you could, that would be free will. But

41:28

if you can't, then you don't have what

41:30

you think you have when

41:34

you're angry with yourself, let's say. And

41:38

you're thinking, I shouldn't have

41:40

done that. That

41:43

to realize, in fact, you

41:45

couldn't have done anything differently. That

41:48

the atomic structure of

41:50

your brain in that moment

41:53

is what made the decision, not

41:55

your free will or yourself or anything

41:57

like that. And

42:01

so it can resolve some upsetting

42:03

feelings. And

42:07

you can discover what those are if you ask yourself,

42:10

would I feel differently towards someone who

42:14

murdered my family, than

42:18

towards a tornado that killed

42:20

my family? Would

42:23

I have a different set of feelings towards

42:25

the tornado than the person?

42:30

And if you do, it's likely that you're imagining that

42:32

the person shouldn't have done that, and

42:36

should have chosen something else. If

42:41

you feel a sense of contempt, or rage,

42:43

or anger, or desire for vengeance, it's

42:46

probably because you believe that they had free will when

42:48

they did that, and they

42:51

chose to do it. They're

42:53

to blame and responsible. And

42:56

if you wanted to get rid of those feelings, you

42:58

could, in a variety of different ways. For

43:02

example, you could dismantle the word

43:04

murderer, and realize that there

43:06

is no such thing. Or

43:12

you could test the theory of free will,

43:15

and see if you have it. And

43:18

when you realize that you don't have it, then

43:20

you don't blame other people. You

43:22

don't get, you have access to

43:25

freedom from contempt,

43:27

rage, anger, a violent

43:30

desire for vengeance. Wow.

43:34

So, you'd be kind

43:36

of, Sam Harris of

43:39

the ilk that we don't have free

43:41

will, and to find, that's a different

43:43

arena from the one

43:45

I'm in, but

43:50

to go into your arena for a minute there,

43:53

that would be similar

43:55

to the Buddhist notion. of

44:01

trying to see things through the

44:04

eyes of the other person, that

44:07

had we been in their body,

44:11

we would have done the same thing

44:13

that they did, and

44:16

also the technique that we

44:18

use sometimes in team therapy

44:20

called forced empathy to

44:23

see why the other person is

44:25

doing what they're doing. Would that

44:27

be a fair summary of... I

44:31

do agree with that. I also think this

44:33

idea has appeared many, many times in many

44:35

different places. I think in

44:37

the Bible there's a saying there, but

44:39

for the grace of God go I.

44:42

Yeah, sure. Or

44:44

even Christ being tortured and

44:47

crucified said, forgive them, they know

44:49

not what they do. Yeah,

44:51

right. And

44:54

so if you'd like to have that kind of peace in

44:56

your mind, then you can experiment with

44:59

and study, try to get

45:01

curious about whether you're choosing

45:04

your experience right now or if

45:06

it's happening. And

45:10

we certainly are under the influence

45:13

of millions of years of evolution

45:15

and preferences and things of

45:17

that nature. And it's

45:20

undoubtedly the case that many people

45:22

are born with a much greater

45:25

disposition in all probabilities, may

45:27

not be politically correct, but greater

45:30

disposition and attraction to violence

45:33

and aggression. Exactly,

45:37

yeah, so that's the nature model. Yeah.

45:41

That our experience is dictated a lot by

45:44

things that happened long before we were born,

45:47

that we didn't control, and so

45:49

we at least didn't choose that portion of what

45:54

our brain is in any given moment. Yeah.

45:59

Robert, supposing that you're not a human being, Polsky also wrote a book

46:01

called Determined that explores this topic

46:03

if people are interested. What was his

46:06

book called? Determined. Determined.

46:09

Oh yes, was his argument exactly the

46:11

same? Similar, yeah.

46:13

I think the cover shows some billiards.

46:17

Oh yeah, sure, billiard balls, yeah.

46:19

Yeah, like physics, sort of like

46:21

an argument around, right, there's no

46:24

ghost in the machine operating it. Yeah, yeah.

46:28

Well that,

46:31

I think you've done a really

46:33

tremendous job of explaining, you know,

46:36

current thinking that humans don't

46:39

have free will. And

46:43

thank you for that.

46:48

You've been very lucid and

46:50

persuasive and you're kind of getting

46:52

us into that mindset of, oh maybe

46:54

people don't have free

46:57

will. My

47:00

own position is a little different from

47:02

that, but I

47:04

think people will love

47:06

what you're saying. And

47:09

certainly anything that gives us

47:11

greater compassion and less

47:14

hatred for other people and less hatred

47:16

for ourselves is gonna be, you

47:19

know, helpful for this lady. I'm

47:22

a little more skeptical

47:24

because without an experience,

47:27

the words are very

47:30

confusing. I think it's a bit like reading

47:34

Wittgenstein, that there's

47:39

another set of experiences or experiments that you

47:42

can run that can help

47:47

see what I'm trying to say

47:49

more clearly. I

47:52

would also say that the method that actually strikes

47:54

me, the methods that strike me most in

47:57

team that approximate this idea,

48:01

One of them is re-attribution. Where

48:04

you're studying what are all of the different causes

48:06

for something that we think shouldn't have happened. Right,

48:10

yeah. And

48:12

when we do... That's the theory I got turned down for a

48:14

date and that proves that I'm a loser. And

48:17

we actually are going to treat somebody with that

48:19

exact belief in a week or two and put

48:21

it on a podcast. Oh, is that

48:23

right? That's exciting. Yeah. The

48:27

live work is always the best. See that again? I

48:29

think the live work is always the best. Oh, yeah, yeah.

48:36

Absolutely. Do

48:40

you want me to give an alternative point

48:42

of view which will seem

48:45

worthless to you? That

48:49

sounds intriguing, yeah. Oh,

48:51

David, I can't believe it. That's

48:54

something worthless. The... I

49:00

don't think this is a matter of

49:02

debating or winning or losing, but just

49:05

that the Wittgensteinian position or the David

49:08

thinking on this, for better

49:10

or worse, was that these...

49:14

The three of you, Matt

49:18

May, Sapolsky and Sam

49:20

Harris, have

49:24

become enchanted by the idea that

49:26

free will doesn't exist. And

49:30

that's... The

49:38

use that you have of... Again,

49:42

free will has been taken out of its

49:44

context of the word free or the

49:46

word will have been pulled out of

49:48

the context of ordinary

49:51

language and put into some metaphysical thing where we're

49:53

going to figure out do we have it or

49:55

do we not have it. And

49:58

my own experience of that... is that

50:02

the question of do we have

50:04

it or not have it

50:08

has no meaning, because

50:11

I don't know what it would

50:13

be like to have free will or not

50:16

to have free

50:18

will. So… That

50:21

is such sweet relief from

50:23

the burden. That is such

50:25

sweet relief from the burden

50:27

of trying to answer meaningless questions.

50:31

You can step out of the prison of trying

50:34

to answer that stuff and

50:37

be free. That's

50:41

helpful at a philosophical level. Yeah,

50:44

and a personal level as

50:47

well. And when I'm working with

50:49

people who have guilt or rage

50:51

directed at others, the idea

50:56

that that person didn't have free

50:59

will is

51:02

not a method that

51:05

I would use, because

51:08

it seems like

51:11

selling highly

51:13

dignified snake oil, you might say,

51:16

something like that. But

51:18

if it's something you feel comfortable with and

51:20

believe in, then you can use that maybe

51:23

in a productive way in your clinical

51:25

work as extra tools, as

51:31

you've been saying. Yeah,

51:35

to say there's no free will is just

51:37

nonsense. Right. helplessly,

52:00

deciphering the noises I'm making into some

52:02

sort of meaning and that you're reacting

52:04

to it, but you're not choosing

52:06

how you react to it. Similarly

52:09

to when you would use the

52:11

relationship journal and you would

52:13

point out, oh you forced the person to respond this

52:15

way. And the reason is

52:17

that they didn't have free will. That's

52:20

my opinion on it. Yeah.

52:25

But you don't have to do the testing. You can't linger

52:27

in the land of language because that's

52:30

where we get lost. It

52:32

doesn't matter. It's no point trying

52:35

to answer philosophical questions. Yeah.

52:37

I don't think I got this idea

52:39

of experimenting that you referred to. Yeah.

52:43

So you have to understand. There's a lot of

52:45

things that we can't do. I remember I took

52:47

table tennis lessons for 20 hours

52:49

a week for six months once. And

52:54

there were things I was trying to get my body

52:56

to do that

52:58

I wasn't very successful at. But

53:01

I didn't feel like I didn't

53:03

have free will. I

53:06

felt like I was too old

53:08

to to learn some of the

53:10

newer approaches to to table

53:12

tennis. I didn't have the coordination.

53:15

But I didn't experience it as a

53:18

you know a loss of free will.

53:21

I experienced it as a deficit of

53:23

skill or a certain kind of coordination.

53:28

Was it frustrating for you or did you

53:30

know it was no

53:32

I just decided after six months I took

53:34

a break from psychiatry as you know. Because

53:38

I thought I could make the Olympic team if I

53:40

got a coach. I

53:42

found out I was wrong. I did get a

53:45

great coach who I got 20 hours a week

53:47

of coaching from one of the top

53:50

a top table tennis

53:53

player. But I but

53:56

I know I was disappointing but it was

53:58

kind of funny though but it was just.

54:00

accepting you know where where

54:02

where I was at and you

54:05

know I was pretty old and

54:07

the people who were coming up

54:09

and coming for for

54:12

Olympic status were like 12 14 6

54:16

16 years old and you

54:19

know I was double or triple that

54:22

but it was it was fun and

54:25

on a few occasions I could get

54:27

into the what I was trying to

54:29

do and then I suddenly was just

54:32

killing people but

54:35

but I couldn't hold that you

54:37

know I couldn't do it

54:39

consistently but

54:42

but it you know was it was a little

54:44

frustrating and disappointing but it was kind of a

54:48

learning experience too and you know

54:50

I could understand very much how

54:52

people feel when they're like young

54:55

and in school and they

54:57

they don't have a certain mental ability

54:59

and the other kids are getting you

55:01

know picking up on things

55:03

really fast and they can't do it that was

55:05

the position that I was in and it

55:08

was kind of you

55:10

know a healthy healthy

55:13

learning thing I would say right

55:18

yeah you can't do

55:20

everything that you want to do you

55:22

know you know what I mean right

55:24

exactly and another maybe another

55:28

way that this concept maps

55:30

onto team for me at least and I don't

55:32

think it does for for you David and I'm

55:34

glad it doesn't I'm glad you're

55:36

expressing a dissenting opinion but

55:39

what one way where I see it is that we

55:41

can't just force ourselves to

55:43

think differently we have

55:45

we have to practice that we

55:48

do all of our patients have to do homework

55:50

every day to look at

55:53

their negative thoughts get them down on paper

55:55

talk back to them and

55:58

only through that practice can Can

56:00

they have a better mindset? Yeah,

56:03

right There's no

56:05

we've got to reprogram our brain

56:07

to do have new circuits Yeah,

56:10

we can't just decide to have different circuitry.

56:12

Yeah in our brain Yeah,

56:14

we will have and even after

56:17

we've recovered and find found our

56:19

enlightenment We'll slip back into those

56:21

old patterns repeatedly. Yeah, and have

56:24

you Yeah,

56:26

that's right So

56:29

we're talking a lot about acceptance also

56:32

Yeah, as well as Commitment

56:35

and training we could have a

56:37

therapy called acceptance and commitment therapy

56:42

Yeah, yeah could catch on Rhonda

56:46

what you know, you're

56:49

gonna pull this together for us.

56:52

I'm gonna say that You

56:55

guys are really deep thinkers and

56:57

I like how you both have brought it back

56:59

to real life examples

57:02

what you just said how does this

57:04

map on to team and the use

57:06

of languaging and languages and What

57:12

you're doing is sparking a lot of opportunity

57:14

to think About

57:16

how these concepts fit into our everyday

57:19

lives It

57:21

it's not just you know random

57:25

theories But really

57:27

how how can we make these practically fit into

57:29

our lives these concepts of free will or do

57:31

I have a self? And

57:33

I imagine that's what this whole month is all gonna is going to

57:35

be about Well

57:38

something like that except my position is

57:40

don't you know You don't have to

57:42

make this fit into your life because

57:44

there's no meaning there. Mm-hmm Title

57:47

this don't listen to this podcast Okay,

57:51

exactly yeah, that's good, I

57:54

guess I just think I'm like super practical so Yeah.

58:01

Yeah, that's the Wittgensteinian

58:04

solution. Yeah,

58:07

that's how

58:09

much time we're going to worry every day about

58:12

having free will. I

58:14

don't know what that means, to

58:18

have free will or not to have free will. I

58:21

know to do something, be free to do something that

58:23

I want to do, and we're very blessed to have

58:25

so many beautiful options

58:27

to living here in America and

58:29

people living throughout the world in

58:32

war zones and horrible

58:34

circumstances and to feel a lot of

58:36

gratitude for that. So

58:38

in a sense, we have more

58:41

freedom, more options than most people

58:43

in the world, and to be

58:45

grateful for that. But

58:49

the worry about whether or not people

58:51

have free will, I wouldn't

58:53

know how to worry about that because I don't know.

58:56

When you put it in that abstract context,

58:59

do we have free will? Without

59:01

a context, it doesn't mean anything.

59:04

And another thing is

59:07

similar to team therapy. Let's

59:10

say someone says, I want to find out what is

59:12

the meaning of life. Well,

59:15

we might say, at what time of day would you

59:17

like to know the meaning of life? Or

59:20

to put it differently, is something bothering you,

59:22

dear? What

59:26

is the problem in your life we could work

59:28

on? We need something real. And once they work

59:30

on something real, like maybe

59:32

a problem with the boyfriend or

59:34

the girlfriend or whatever the conflict

59:36

with parents. And when that

59:39

thing gets solved, then, oh, I'm not

59:41

so concerned about the meaning of life

59:43

anymore. And that's also like a Wittgensteinian

59:45

solution. But when I

59:47

was a resident, psychiatric resident, we did

59:49

not do that. We let people ramble

59:51

on and on and on, exploring their

59:54

childhood or talking about all the problems

59:56

in their life as if there was

59:58

something going to happen. emerge from that

1:00:00

like a Phoenix bird was

1:00:02

suddenly going to rise from the ashes

1:00:05

and I never once saw it happen.

1:00:08

And so I think the Wittgensteinian

1:00:10

aspect here is, and

1:00:13

team, we're focusing on a specific

1:00:15

problem at a specific moment in

1:00:17

your life and all of your problems

1:00:19

will be encapsulated there. And

1:00:22

going after abstract concepts like

1:00:25

self-esteem or the meaning of life or

1:00:27

things of that nature are

1:00:29

generally going to be kind of a waste of time. And

1:00:36

to continue my sort of enchantment with

1:00:38

this idea that in

1:00:41

fact there's not what we imagine we

1:00:43

have when we believe that we

1:00:45

have free will. If we imagine

1:00:47

that we can make some decision

1:00:50

different from what our brain

1:00:53

is deciding is

1:00:55

that we don't want to accept that reality. Because

1:00:59

we like to feel proud of our accomplishments. We

1:01:03

like to imagine that we chose to

1:01:06

do this amazing thing that we've done and we

1:01:09

kind of like to blame others too. We

1:01:12

like to get angry with others and say that they shouldn't

1:01:14

have done that thing. They have they

1:01:16

had some other different choice in the

1:01:18

matter. But if you want to

1:01:20

overcome those feelings this is one way to do that. There

1:01:23

are many ways but re-attribution

1:01:25

or discovering

1:01:27

there's no free will can

1:01:30

help let go of those negative feelings. And those

1:01:32

are my thoughts on it. Awesome.

1:01:38

Often an agenda-setting problem. Yeah.

1:01:43

And one last thing I would say

1:01:45

is that I think you

1:01:48

like the idea of people that free

1:01:50

will would have a meaning and that

1:01:52

we wouldn't have it would have a

1:01:54

meaning. You like that and so you

1:01:57

want to cling to this issue. the

1:02:00

feeling of forgiving and letting go

1:02:02

of hatred and anger towards anybody.

1:02:05

It just feels so nice to

1:02:07

get that piece from

1:02:09

that level. It does, absolutely.

1:02:12

And another lesson there from team

1:02:14

that I had forgotten about is

1:02:17

that if someone is motivated to have

1:02:19

a particular belief, then,

1:02:21

you know, like I'm

1:02:23

a loser, then you can't

1:02:26

talk them out of it. You can't help

1:02:28

them. Right. But you can try to

1:02:30

reduce their resistance and kind

1:02:32

of come in through a side door, which is what

1:02:34

we come in with team. But it's

1:02:37

the same in philosophy that if you want

1:02:39

to have a particular, or in religion, if

1:02:41

you want to have, or in politics, if

1:02:43

you strongly want to have a

1:02:46

particular belief, then all

1:02:48

the evidence in the world will not

1:02:50

deter you from that

1:02:52

belief. And

1:02:55

you end up back in the prison of your own thinking, feeling

1:02:58

bothered by it. Yeah. Excellent

1:03:01

point. Yeah. Wow. Okay.

1:03:05

Okay. Shall we say Sayonara?

1:03:08

Now would be a good time to do that. Okay.

1:03:12

Well, thank you, Matt and David. This was

1:03:14

really an interesting podcast to not

1:03:16

listen to and to let go of as soon as we're done

1:03:18

listening to it. Absolutely.

1:03:21

And we'll see you next week. This

1:03:24

has been another episode of the Feeling

1:03:26

Good podcast. For more information,

1:03:28

visit Dr. Burns website at feelinggood.com,

1:03:31

where you will find the show

1:03:33

notes under the podcast page. You

1:03:35

will also find archives of previous

1:03:37

episodes and many resources for therapists

1:03:39

and non-therapists. We welcome your comments

1:03:41

and questions. If you want to

1:03:44

support the show, please share the

1:03:46

podcast with people who might benefit

1:03:48

from it. You could also go

1:03:50

to iTunes and leave a five star rating. I

1:03:52

am your host, Rhonda Barofsky, the director

1:03:55

of the Feeling Great Therapy

1:03:57

Center. We hope you enjoyed

1:03:59

this episode. I invite you to

1:04:01

join us next time for another episode of

1:04:03

the Feeling Good Podcast.

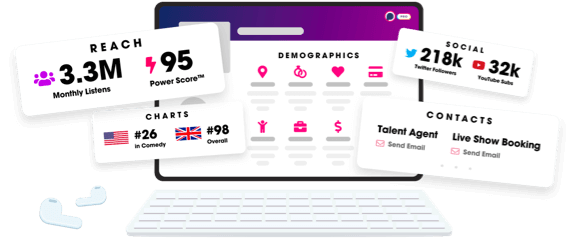

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us